|

|

Report to the Congress on Practices of the Consumer Submitted to the Congress pursuant to section 1229 of June 2006

IntroductionIssuers of revolving consumer credit in the form of credit cards use increasingly sophisticated tools to identify potential customers on the basis of their expected ability and willingness to repay. With the development of this "customer segmentation" process, lenders have been able to extend credit cards to a growing number of customers with an increasingly wide range of credit characteristics.1 Access to revolving credit provides consumers with a convenient mechanism to purchase goods and services, and such credit has in part replaced more cumbersome and less convenient forms of credit. However, the expansion of revolving consumer credit has raised concerns that it may sometimes be made available to consumers who are not capable of repaying and that the accumulation of such debt may contribute to consumer insolvency. Section 1229 of the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005 requires the Federal Reserve to report to the Congress on the methods by which issuers of consumer credit choose the consumers they solicit for credit and how issuers choose the consumers to whom they will provide credit; the report is to pay particular attention to how consumer credit issuers determine whether a consumer will be able to repay the debt. It also requires the Federal Reserve to report on whether the industry's practices in these matters encourage consumers to accumulate additional debt. Finally, it requires the Federal Reserve to report on the effects of credit solicitation and extension on consumer debt and insolvency. This report is submitted in fulfillment of the Federal Reserve's obligations under section 1229 of the act.2 Back to Contents Scope of the ReportThis report focuses on credit card debt, in keeping with statements made on the floor of the Senate in 1999 by the principal sponsor of the amendment that added section 1229 to the act that was ultimately passed.3 The report presents a brief history of revolving credit and discusses the factors that explain the growth of revolving consumer credit over time, focusing on the relationship of this growth to household indebtedness and bankruptcy. Data for this part of the report come from primary sources, such as the Federal Reserve's Survey of Consumer Finances, and from industry sources and the economic literature. Next, this report discusses the practices used by bank issuers of credit cards to solicit customers and extend credit, including the methods they use to determine whether a consumer will be able to repay his or her debt. This discussion is based on the general knowledge of these practices that the Federal Reserve has acquired, particularly in its capacity as an agency responsible for ensuring the safety and soundness of banking organizations and through its experience working with the other federal and state financial institution regulatory agencies responsible for supervising bank credit card issuers.4 The final section of the report describes the tools used by banking supervisors--including examinations, supervisory guidance, and enforcement activities as necessary--to discourage unsafe and unsound lending practices and discusses recent supervisory guidance aimed at curbing certain practices by lenders. Consistent with section 1229, this report focuses on the decisionmaking processes of credit card issuers as they prescreen potential customers, review applications, and manage consumer accounts. A discussion of consumer debt must acknowledge, however, that consumers ultimately make the decision about whether to apply for credit and how much to borrow. Some observers have raised concerns about whether consumers have enough information to make good decisions and avoid unexpected costs and whether some practices and products of issuers affect consumers unfairly. These concerns are beyond the scope of this report.5 Back to Contents Key FindingsAs both revolving credit use and consumer bankruptcies have grown in recent years, concerns have emerged about whether there is a causal relationship between the two trends and, in particular, whether the practices of credit card issuers have contributed to household insolvencies. The first three of the four requests by the Congress in section 1229(b) require a study of the extent to which, in soliciting customers and extending credit to them, the consumer credit industry does so (A) "indiscriminately," (B) "without taking steps to ensure that consumers are capable of repaying the resulting debt," and (C) "in a manner that encourages consumers to accumulate additional debt." The fourth request is to study the effects of the industry's solicitation and credit extension practices "on consumer debt and insolvency." Regarding the first two points, this review finds that as a matter of industry practice, market discipline, and banking agency supervision and enforcement, credit card issuers do not solicit customers or extend credit to them indiscriminately or without assessing their ability to repay debt. Currently, the principal means of solicitation is direct mail, the bulk of which is guided by careful prescreening of potential recipients regarding their financial condition and history. And all applications received are reviewed for risk factors. Thus, lenders analyze consumer financial behavior carefully before offering credit, and they consider consumers' ability and willingness to pay in making decisions about extensions of credit. Regarding the third point, whether the industry encourages consumers to accumulate debt, we find that (beyond the basic fact that a credit account represents an agreement allowing the customer to acquire debt), the aggregate growth of consumer debt has not entailed a threat to the household sector of the economy; nonetheless, certain specific industry practices of late have been deemed by regulators to potentially extend borrowers' repayment periods beyond reasonable time frames and have been the subject of extensive supervisory attention and guidance. Finally, regarding the effect of industry practices on consumer debt and insolvency, we find that although the percentage of families holding credit cards issued by banks has risen from about 16 percent in 1970 to about 71 percent in 2004, the household debt service burden has increased only modestly in recent years. The data have consistently shown that the vast majority of households repay their revolving debt on time.6 The data also indicate that delinquency and default experience vary for different segments of the population, but such diversity is to be expected, as lenders have expanded access to credit to a broader population. Back to Contents BackgroundIndividuals have entered into debt obligations since antiquity, but consumer credit is a relatively modern phenomenon. Beginning in the nineteenth century, installment payment plans were made available by sellers for purchases of furniture, sewing machines, and other domestic goods. Before the 1920s, however, there were few demands for credit for automobiles, durable goods, college tuition, and home modernization and repair that make up the bulk of consumer credit use today. Also, few financial institutions in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were willing to extend consumer credit; lenders did not have sufficient information to assess the creditworthiness of most individual borrowers, and the costs of managing such loans in any number would have been prohibitively high. Much of the demand for consumer credit arose with the growth of urbanization and the mass production of consumer goods. These developments began in the nineteenth century and have become especially strong since World War II. Today, credit use by consumers is ubiquitous. According to the Federal Reserve's most recent Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), about 76 percent of U.S. families carried some form of debt in 2004 (table 1); an even higher proportion of families carried debt at some earlier point in their lives. Credit use is prevalent among families of all types. For example, in 2004, debt was carried by about 90 percent of families in the top two income quintiles (derived from table) and by about 53 percent in the lowest income quintile. Similarly, except for families headed by a retired or elderly individual (defined as being 75 years of age or older), most families carry debt regardless of the age, race, ethnicity, and work-force status of the household head and regardless of the household's housing status (own versus rent) and net worth.7

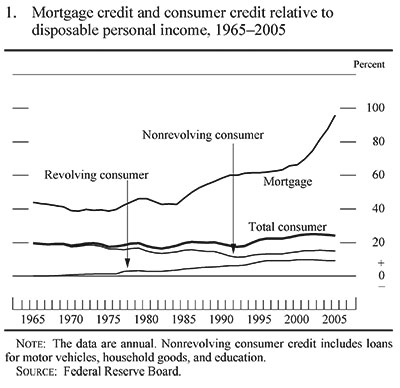

* Ten or fewer observations. Return to table Source: Federal Reserve Board, Survey of Consumer Finances. Back to ContentsGrowth of Revolving Consumer CreditAs the economy grew in the post-World War II period, consumers' use of credit increased substantially relative to their income. Most of the credit growth relative to income has been in the form of mortgage credit (figure 1). Excluding mortgage credit, revolving consumer credit has risen both as a share of total consumer credit and relative to income over the past four decades.  d dAccording to the SCF, about 71 percent of families held general-purpose credit card accounts issued by banks in 2004, up from about 16 percent in 1970 (table 2). Financial institutions today offer these cards under brand names such as MasterCard, Visa, American Express Optima, and Discover. Estimates by the credit card industry indicate that almost 600 million bank-type credit cards were outstanding nationally at the end of 2004, up from about 370 million a decade earlier (table 3).

Note: In 1970, respondents were asked about using credit cards; in all other years, they were asked about having cards. In the years 1995-2004, retail card holders included some respondents with open-end retail revolving credit accounts not necessarily evidenced by a plastic card. 1. Includes cards issued by banks, gasoline companies, retail stores and chains, travel and entertainment card companies (for example, American Express, and Diners Club), and miscellaneous issuers (for example, car rental and airline companies) Return to table 2. Data are for 1971. Return to table 3. A bank-type card is a general-purpose credit card with a revolving feature; cards include BankAmericard, Choice, Discover, MasterCard, Master Charge, Optima, and Visa, depending on year. Return to table 4. "Carrying a balance" defined as having a balance after the most recent payment. Return to table Source: Federal Reserve Board, Survey of Consumer Finances.

1. Includes general-purpose cards with a revolving feature issued with the Discover, MasterCard, and Visa brands; travel and entertainment cards with the American Express brand; and cards issued in the name of retail outlets. For the years 1999-2001, included MasterCard and Visa offline debit cards. Return to table 2. Includes general-purpose cards with a revolving feature issued with the Discover, MasterCard, and Visa brands. For the years 1999-2001, included MasterCard and Visa offline debit cards. Return to table 3. Before 1999, included Visa debit cards. Return to table Source: Calculated from Thomson Financial Media, Cards and Payments: Card Industry Directory, various editions (New York: Thomson Financial Media, pp. 14 and 16 in each edition). Evidence from the SCF shows that revolving consumer credit (mostly credit card debt) has partly replaced certain types of closed-end installment credit, principally those types classified as nonautomobile durable goods credit, home improvement loans, and "other." These three categories declined from a total of 20 percent of consumer credit in 1977 to 10 percent in 2004 (table 4). In contrast, the percentage of consumer credit represented by revolving credit rose from about onetenth or less in the 1970s to a range of one-fifth to one-fourth since then (table 4).

Note: Components may not sum to totals because of rounding. 1. In 1970, non-automobile durables included all the other non-automobile categories. Return to table . . . Not applicable. Return to table Source: Federal Reserve Board, Survey of Consumer Finances. The increase in the share of revolving consumer credit relative to total consumer credit outstanding reflects (1) technological advancements; (2) widespread deregulation of interest rates, which permitted card issuers to more effectively price for credit risk; (3) the growing use of credit cards as payment devices and not simply for borrowing; (4) improvements in the ability of companies to segment customers by risk, which expanded access to a much larger population; and (5) securitization by financial institutions of their credit card receivables, which has helped lower their cost of funds. Back to Contents Technological AdvancesTechnological advances are continually reducing the unit costs of data processing and telecommunications, and they have in turn greatly expanded the ability of creditors to offer access to revolving credit at millions of retail outlets and automated teller machines (ATMs) worldwide. Moreover, advances in the technology of credit-risk assessment and the breadth and depth of the information available on consumers' credit experiences have made it possible for creditors to quickly and inexpensively assess and price risk and to solicit new customers. These advances have spurred the rapid growth of revolving credit. Back to Contents Financial DeregulationUntil the late 1970s, state usury laws established limits on the interest rates credit card issuers could charge on outstanding balances, which limited issuers' ability to price for credit risk. Beginning in the late 1970s, court decisions and legislation by some states relaxed the restrictions on credit card interest rates, allowing national banks based in those states to charge market-determined rates throughout the country. The reduction in legal impediments, together with improvements in data processing and telecommunications, allowed for the development of risk-based pricing nationally and contributed to the growth of revolving credit. Back to Contents Revolving Credit as a Payment MechanismCredit cards offer consumers not only a convenient way to borrow but also an important means for making routine payments. Many consumers (about 56 percent in 2004, according to the SCF) report that they rarely carry an outstanding balance on their cards--that is, that they nearly always pay in full upon receipt of the credit card statement at the end of each monthly billing cycle (table 5). The use of credit cards for routine payments rather than for long-term borrowing has grown for many reasons. Cards minimize the need to carry cash and maintain high checking account balances; they are easier to use than checks and, therefore, more convenient for consumers; they offer consumers a convenient record of their spending patterns; and, in many cases, credit card spending earns rewards such as cash-back incentives or travel discounts. At the same time, consumers have shown that they prefer the convenience of prearranged lines of credit to the costs and inconvenience of applying for credit before every contemplated use. Consumers also are attracted to credit cards because of the protections they afford, principally the limited liability associated with their unauthorized use. From the merchant's perspective, credit cards limit the risk of loss or theft associated with carrying and handling cash, and they minimize bad-debt risk. Finally, they are attractive to both consumers and merchants because they are accepted worldwide.

Source: Federal Reserve Board, Survey of Consumer Finances. Back to ContentsSegmentation of CustomersIn the past, many potential credit customers found access to credit difficult because banks lacked sufficient information to judge their creditworthiness and were therefore unable to price for various levels of risk. The emergence of national credit reporting agencies that provide comprehensive and inexpensive credit-related information about the bulk of the adult population and the widespread use by lenders of automated statistical models for evaluating risk have contributed importantly to the development of risk-based pricing.8 As a result of these developments, evaluation of the creditworthiness of large numbers of consumer accounts, including accounts with low balances, has become less expensive, and credit cards have become more widely available to all groups, including lower-income consumers (table 6), and to populations with a wider range of credit risks.

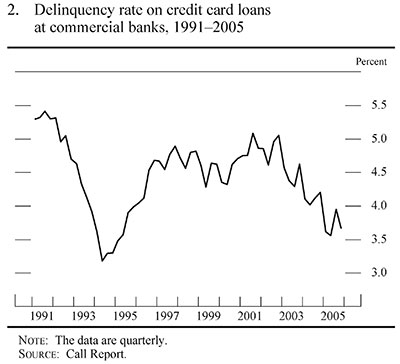

Note: In 1970, respondents were asked about using cards; in all other years, they were asked about having cards. Proportions that have a card are percentages of all families; proportions carrying a balance are percentages of holders of bank-type cards that had an outstanding balance after the most recent payment. Components may not sum to totals because of rounding. Source: Federal Reserve Board, Survey of Consumer Finances. Improvements over time in risk-screening technology and account management techniques, such as controls on credit limits, appear to have helped offset the credit risks related to wider consumer access to revolving credit. For example, in recent times, delinquency levels on credit cards have varied within a fairly narrow band, and today's average levels of delinquency are not high by historical standards (figure 2).  d dOf course, aggregate statistics do not illustrate the diversity of delinquency experience across consumers and individuals grouped by various characteristics, such as income and wealth. For example, information from the Survey of Consumer Finances generally shows that lower-income families have higher rates of delinquency than higher-income families (table 7).9 It's not surprising to observe different delinquency experiences across the population given variations in credit-risk profiles.

Source: Federal Reserve Board, Survey of Consumer Finances. The ability to price for credit risk allows lenders to increase access to credit without compromising profitability. Available data suggest that commercial banks specializing in the extension of revolving credit through credit cards are markedly more profitable than commercial banks in general (table 8).10

Note: Credit card banks are commercial banks with average managed assets (including securitizations) of at least $200 million (current dollars) with a minimum of 50 percent of assets in consumer lending and of 90 percent of consumer lending in the form of revolving credit. Profitability of credit card banks is measured as net pretax income as a percentage of average quarterly assets. Profitability of all commercial banks is measured as pre-tax income as a percentage of average net consolidated assets. Source: For credit card banks, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2005), The Profitability of Credit Card Operations of Depository Institutions, annual report to the Congress (Washington: Board of Governors, June); for all commercial banks, Federal Reserve Bulletin, various issues. Back to ContentsSecuritizationTraditionally, credit card issuers held the bulk of their credit card receivables in their own portfolios. The amount of credit they could offer was limited by the availability and cost of banking funds and equity capital. However, over the past twenty-five years, new sources of funds and a general decline in the cost of funds have helped expand the availability of credit cards. Securitization has provided a significant source of funding and liquidity for portfolios of credit card receivables (table 9). Institutions that issue credit cards have, for a number of years, securitized more than half of credit card receivables outstanding, in the process tapping domestic and international capital markets to fund credit card lending.

Source:

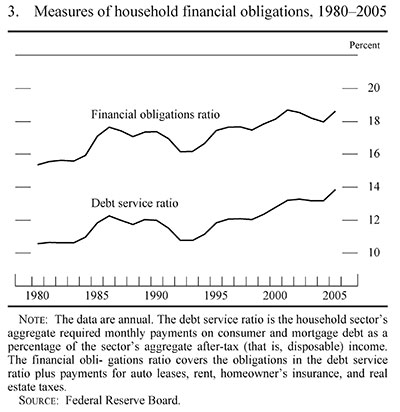

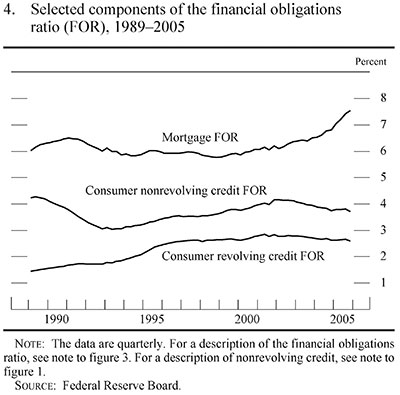

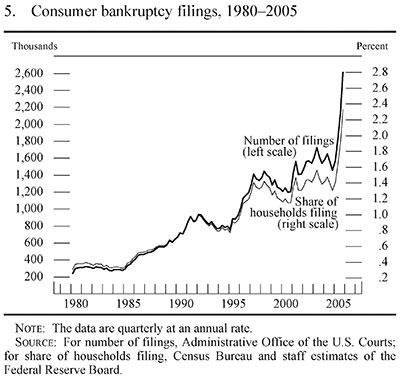

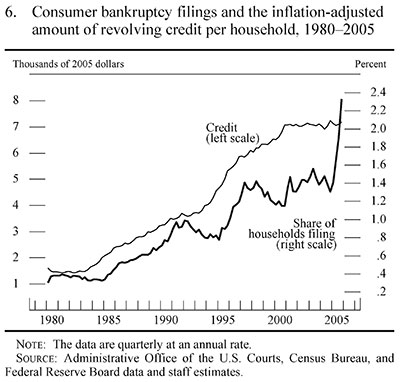

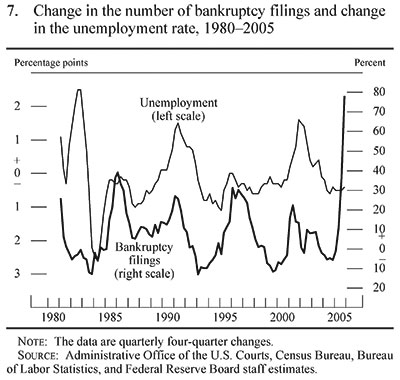

Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, Consolidated Reports Contribution of Credit Cards to Consumer Debt Burdens and InsolvencyThe Burden of Household Debt ServiceSection 1229 requires the Board to examine whether the practices of the credit card industry with respect to soliciting and extending credit may contribute to rising consumer debt burdens and insolvency. There are various measures of the burden of debt, but the most useful compare monthly cash flows--specifically, debt service costs--relative to income. The household debt service ratio (which covers monthly aggregate required payments of all households on mortgage debt and both revolving and nonrevolving consumer loans relative to the aggregate monthly after-tax income of all households) has increased only modestly and has fluctuated over a fairly narrow range of about 3 percentage points over the past twenty-five years (figure 3). A broader measure, the financial obligations ratio (which covers the payment requirements in the debt service burden plus required payments on automobile leases, rent on tenant-occupied property, homeowner's insurance, and real estate taxes, all relative to after-tax income), has trended up at about the same rate as the debt service burden since 1980 but has changed little in the past five years. Neither the debt service ratio nor the financial obligations ratio suggests that consumers in the aggregate face excessive debt service burdens.  d dThese findings seem inconsistent with certain widely held beliefs. For example, when asked in a recent survey whether large numbers of credit card solicitations had caused other consumers to take on too much debt, about 85 percent of respondents answered affirmatively (data not shown in tables).11 Back to Contents Measuring Financial DistressThe Survey of Consumer Finances provides an opportunity to profile changes in debt burdens for different groups of consumers over time. For all households, the aggregate debt service burden increased modestly from 2001 to 2004 (the latest available data), but the rate was lower in 2004 than in 1998 and little changed from 1992 (table 10).

Source: Federal Reserve Board, Survey of Consumer Finances. Back to ContentsA limitation of the aggregate ratio of debt payments to income is that it reflects only a typical household and may not be indicative of financial distress. A more compelling indicator of distress is the proportion of households with an unusually large ratio of total payments to income--say, 40 percent. Over time, the proportion of households with payments exceeding 40 percent of their income has fluctuated in a fairly narrow range, from a low of 10 percent in 1989 to a high of 13.6 percent in 1998. From 2001 to 2004, the proportion edged up 0.4 percentage points, to 12.2 percent (table 10). Although the 2004 Survey of Consumer Finances indicates that households with incomes in the lowest quintile of the income distribution are more likely to have elevated payment burdens, there is little evidence that this proportion is rising. In fact, over the years 2001-04, the proportion of households with debt service burdens of more than 40 percent fell for households in the lowest quintile of income. Moreover, other research has suggested that although the proportion of families with high indebtedness had remained approximately the same, it is not necessarily the same families who remain heavily burdened by debt over time. A re-interview in 1986 of many respondents interviewed for the 1983 Survey of Consumer Finances found that in the group with the highest debt service burden in 1983, more than 28 percent had no consumer debt at all by 1986, and the payment burden of another 28 percent was less than 10 percent of income. Most notably, less than 9 percent of those in the highest payment-burden category in 1983 remained in that category in 1986.12 The design of the surveys after 1986 has not permitted a similar re-interviewing of the participants. Payments on revolving credit, mortgages, and nonrevolving credit are the credit-related components of the financial obligation ratio. Among the three categories, revolving credit contributes the smallest share of credit-related components (about 20 percent) and of the total financial obligation ratio (about 15 percent) (figure 4).13 The revolving credit component is higher now than it was some fifteen years ago but has changed little over the past several years. A closer examination of the revolving credit component suggests that it would have hardly changed at all over the past fifteen years except for expanded use of credit cards as a payment mechanism and the rise in the share of households with a credit card.  d Back to Contents d Back to ContentsCauses of BankruptcyAnother measure of household financial distress is bankruptcy filings, which have risen over the past twenty-five years (figure 5). In 2004, about 1.56 million households, or about 1.4 percent of all U.S. households, filed for bankruptcy. In the second half of 2005, bankruptcy filings increased sharply ahead of the October enactment of the stricter bankruptcy provisions passed by the Congress.  d dThe rate at which consumers file for bankruptcy has broadly trended up with the real value of revolving consumer credit per household (figure 6). This correlation is not surprising, as the vast majority of bankruptcies involve some consumer credit. This historical correlation broke down in 2005 as the number of filings spiked in advance of the change in the bankruptcy law.  d dThe circumstances leading to bankruptcy are varied and often unpredictable. Studies have attempted to explain why individual households file for bankruptcy and to explain why the total number of bankruptcy filings continued to rise in the 1990s despite rising incomes and declining unemployment. Researchers have used results from nationally representative surveys of households, surveys of recent bankruptcy filers (both simple questionnaires and in-depth interviews), data from credit card lenders, and records from the credit reporting agencies. Broadly speaking, three main explanations of household bankruptcy have emerged from these studies: (1) the adverse-event theory, which argues that households file for bankruptcy primarily because of job loss, divorce, or other events that adversely affect earnings or nondiscretionary spending; (2) the strategic bankruptcy theory, which argues that households respond to the financial benefit of filing for bankruptcy; and (3) the spillover theory, which argues that households are more likely to file for bankruptcy if a friend or relative has done so, either because of diminished stigma or because households learn about bankruptcy by word of mouth. These three theories are not mutually exclusive. Very few households borrow money without intending to repay it; generally it is only after adverse events with serious financial implications that borrowers tend to miss payments and, eventually, seek bankruptcy protection. Moreover, researchers believe that social networks play an important role in job search and other important household decisions, so it seems reasonable that the decision of one household to file for bankruptcy could affect other households' decisions. The decisions of consumers to file for bankruptcy and the experience of consumers in bankruptcy have stimulated a rich literature of descriptive and scientific studies. In recent years, attention has focused on the extent to which households could benefit financially by filing for bankruptcy, that is, on whether some households use consumer bankruptcy "strategically," and on whether the stigma associated with bankruptcy is declining. A study by White established that 15 percent of households could realize an immediate financial gain from filing for bankruptcy; in effect, their dischargeable debts exceed their non-exempt assets.14 However, the fact that the actual filing rate is much lower suggests that many households forgo the immediate financial benefit of bankruptcy. White and other authors have advanced a variety of different explanations for this apparent puzzle. First, households may not consider the financial benefit of filing; that is, they may be nonstrategic in their use of bankruptcy protection. Instead, households would be forced into bankruptcy only after a series of adverse events. Second (a related explanation), debtors may simply stop making payments on their debts if they do not expect lenders to act aggressively to collect debts. Third, because debtors generally can file under chapter 7 of the bankruptcy code only every six years, strategic households might value waiting to file bankruptcy until the benefit is even greater. Fourth, households may only temporarily find themselves with dischargeable debts exceeding their nonexempt assets; filing for bankruptcy results in a lower credit rating and constrained access to credit in the future; and the household may anticipate exposure to some stigma or shame as a result of filing. These negative consequences could outweigh the immediate benefit of filing, especially if the household expects its financial situation to improve. Using data from a credit card lender, Gross and Souleles show that, after controlling for a variety of risk factors, households have become more likely to file for bankruptcy over time.15 More broadly, consumer bankruptcy rates rose in the 1990s even as unemployment fell and incomes rose, leading many commentators to suggest that the stigma associated with bankruptcy must have faded over that period. A study by Athreya, however, uses a quantitative model of credit supply and demand to argue that a drop in stigma is unnecessary to explain the rise in bankruptcies during the 1990s.16 Fay, Hurst, and White study in some detail the bankruptcy decisions of a representative crosssection of U.S. households.17 They find that the strongest predictor of whether a household files for bankruptcy in a given year is the financial benefit of doing so. They also find that, controlling for household-level factors and state bankruptcy laws, households are more likely to file for bankruptcy if they live in a state in which bankruptcy filing rates are generally high. Overall, Fay, Hurst, and White adduce strong evidence that households understand bankruptcy laws and that these laws affect their behavior. Nonetheless, Gan and Sabarwal indicate that they cannot rule out the hypothesis that adverse events such as unemployment provide the triggers that push households into bankruptcy.18 The unemployment rate directly measures one of the most important sources of household financial distress, and, indeed, increases in the unemployment rate are followed, after a delay of about three calendar quarters, by increases in the bankruptcy rate (figure 7).  d dStudies of bankruptcy records and interviews with a variety of households by Sullivan, Warren, and Westbrook and by Warren and Tyagi portray the events leading up to a typical bankruptcy filing.19 Typically (although not always), households in financial distress will become delinquent on some of their outstanding debts before seeking bankruptcy protection. However, some households skip this stage and file for bankruptcy without any delinquent accounts. Also, some households choose "informal bankruptcy," in which they stop making payments on their debts but do not seek the protection of formal bankruptcy.20 On balance, then, it appears that the longer-run trend in bankruptcy filings is historically related to a number of factors, including an increase in revolving consumer credit use and, perhaps, a decline in the stigma associated with bankruptcy. It also appears that the decision to declare bankruptcy is typically triggered by unforeseen adverse events such as job losses or uninsured illnesses.21 Back to Contents Managing Credit RiskAll lending poses credit risk, that is, the risk of economic loss due to the failure of a borrower to repay according to the terms of his or her contract with the lender. Within any given loan portfolio--that is, any group of loans defined by the issuer--a certain percentage of borrowers will be unable or unwilling to meet their obligations. Because it is impossible to know with certainty which borrowers will fail to repay their debt in accordance with their contracts, financial institutions seek to manage consumer credit risk by estimating the probability and expected size of losses for each portfolio. In general, managing credit risk involves forecasting the ability and willingness of borrowers to repay their debts. For credit card lenders, a key component of credit-risk management is the credit score. An individual's credit score reflects the credit risk posed by that customer given certain performance criteria, including his or her behavior in managing financial obligations. Lender ratings of potential borrowers have become increasingly sophisticated and automated over the past decade. Lenders use extensive information on borrowers available from credit reporting agencies and from proprietary databases. This information is combined with new quantitative modeling techniques--which help lenders rank prospective borrowers on the basis of historical information about borrowers with similar quantifiable characteristics--to guide the determination of which prospective borrowers in each portfolio will be extended credit and the pricing of that credit. Scoring models, when rigorously developed and regularly updated and validated, enable the efficient review of large numbers of customers and form the basis of most credit decisions in the credit card industry. These decisions are occasionally supplemented by qualitative judgments to reach a final credit decision. The following sections focus in greater detail on the key considerations for credit card issuers during the three basic stages of managing credit risk: (1) "prescreening"--reviewing the records of potential borrowers before deciding to solicit their business, (2) the review of applications from potential borrowers, and (3) account management. Back to Contents PrescreeningIn today's credit card market, issuers pursue new customers with benefits such as reward programs, automobile roadside assistance, and financial incentives including introductory ("teaser") rates, balance transfers at low interest rates, and flexible payment programs. The varied product offerings provide choices for customers while allowing the creditor to tailor incentives and products to specific segments of the market and to price them in a way that reflects the underlying risk of each segment. Issuers use a variety of channels to establish relationships with consumers.22 The most common channels are direct mail, telephone solicitations, television and print advertisements, electronic mail, the Internet, promotional events, and "take one" brochures. In recent years, the most important of these by far in terms of numbers of solicitations has been direct mail. Industry sources indicate that mail solicitations have grown substantially over the years and have averaged close to 5 billion annually since 2001, a volume about five times as large as it was a decade earlier (table 11). According to these sources, in a recent year, 70 percent of general-purpose credit card accounts were initiated from direct-mail contact, and three-fourths of those mailings were prescreened (table 12); another 15 percent of accounts were derived from telephone inquiries initiated by the customer or the creditor. In recent years, the growth in mailed solicitations has been driven by the declining cost of producing and mailing marketing materials and the rise of other operational efficiencies. However, as the number of mailed solicitations has grown, response rates have fallen, reaching a record low of 0.4 percent in 2004--a trend that may reflect a mature market (table 11).

Source: Mail Monitor, Synovate (www.synovate.com).

Source:

Information Policy Institute (2003), The Fair Credit Reporting Act: Access, The main reason for the growing dominance of solicitations in the customer-acquisition process is that, with current technologies and methods, issuers can prescreen potential customers, sorting them by credit experience and creditworthiness. In prescreening, an issuer establishes specific credit criteria, such as a credit score, and either (1) requests from a credit reporting agency the names, addresses, and certain other information on consumers in the credit reporting agency's database who meet those criteria or (2) provides a list of potential customers to the credit reporting agency and asks the credit reporting agency to identify which individuals on the list meet those criteria. Prescreening requests may be made to the credit reporting agency directly by the issuer or through a third-party vendor. Federal law allows a credit reporting agency to give lenders information on consumers for prescreening purposes only if all of the following three conditions are met: (1) "the transaction consists of a firm offer of credit or insurance," (2) prescreening is used solely to offer credit or insurance, and (3) the consumer has not elected to "opt out" of such solicitations.23 A "firm offer of credit or insurance" is defined as any offer of credit or insurance that will be honored if, on the basis of information in a credit report, the consumer meets the specific criteria used to select the consumer for the offer; the lender may, however, verify the accuracy of the information used to select the consumer for the offer (for example, verification of income and employment). Companies using prescreening have found that it facilitates the solicitation process by focusing on consumers who satisfy the established credit criteria, thereby reducing the cost of acquiring customers. Prescreening allows creditors to avoid the cost of sending solicitations to large numbers of consumers who ultimately would not qualify for, or be interested in, the credit products offered. Creditors can prescreen on the basis of measures of credit risk, such as the credit score, or on measures of account usage, such as the number of credit cards currently held or the size of balances outstanding. Also, creditors have found that by having access to credit information at the prescreening phase, they are better able to control certain risks related to offering their products. For example, by prescreening, a creditor can use the information in a credit file twice, once to select prospective customers and a second time to verify that no substantive change has occurred in the credit status of the prospective customer. Having information about the credit circumstances of a customer at two points in time increases the creditor's ability to manage risk involving that consumer. Back to Contents Application ReviewDuring the application process, credit card issuers decide on the customers to whom they will extend credit and set the credit limits, rates, and terms on the accounts. Credit card issuers consider a number of factors in making these determinations, including a consumer's credit history (generally summarized by a credit score), various measures of debt burden, income, employment status, length of employment, homeownership, and rental or mortgage history. Some of this information is obtained from credit reporting agencies, and some, such as income and homeownership, is provided by the consumer in the application process. Credit card issuers use this information to calculate certain ratios, such as debt to income and debt service to income, that can help predict repayment capacity, that is, the ability and willingness to pay. Credit card issuers rely on experience to judge whether or not it is worth the cost to independently verify information, such as income, that is reported by an applicant, and they perform such verifications only rarely. Verification can be a time-consuming and expensive process and does not necessarily provide meaningful new information to credit card issuers. Back to Contents Account ManagementAccount management by the lender encompasses the monitoring of account usage and payment patterns to maintain the credit quality of the portfolio. In pursuit of that goal, issuers may amend credit lines, rates, terms, and minimum payments as necessary. Issuers frequently test and analyze the effectiveness of these practices both on individual accounts and on portfolios of accounts. Another aspect of account management is the administration of "workout" and "forbearance" programs, which are designed to help customers who are unable to meet their contractual obligations and to minimize credit losses to issuers. Credit card issuers design these programs to maximize the reduction in the amount of principal owed over a reasonable period of time, typically sixty months. To meet these time frames, institutions may need to substantially reduce or eliminate interest rates and fees so that more of the payment is applied to reduce principal. In addition, institutions sometimes negotiate settlement agreements with borrowers who are unable to service their unsecured open-end credit. In a settlement arrangement, the institution forgives a portion of the amount owed. In exchange, the borrower agrees to pay the remaining balance either in a lump-sum payment or by amortizing the balance over several months. Back to Contents Regulation of Revolving Consumer CreditDepending on its charter, a financial institution that conducts credit card lending is subject to supervision and regulation by one or more of the following federal agencies: the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the National Credit Union Administration, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), and the Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS); it may also be subject to oversight by state banking regulators. Federal and state regulators are required by the relevant statutes to periodically examine banking organizations to determine overall safety and soundness, including the quality of their risk management infrastructure and financial condition. Banking organizations are also subject to rules and regulations that seek to protect consumers by ensuring that they receive adequate information about their accounts and by establishing certain ground rules for the credit solicitation process. The supervisory oversight of banking organizations for safety and soundness emphasizes the adequacy of risk-management policies and practices, including the management of credit risk and other risks generated by these activities. When examining the credit card operations of banking organizations, examiners review policies and procedures for product development, customer solicitation, application review, and account management. As part of this process, examiners engage in varying levels of verification and validation of the practices and processes used by banking organizations, including, in many instances, the testing of customer accounts to assess whether a bank is adhering to its stated policies and procedures. Also, given the extensive use of modeling in the credit process, examiners review the oversight and control processes banks use to test and validate their models. As risk management is a constantly evolving discipline, banking supervisors continually work with banking organizations to encourage implementation of improved risk management tools. Back to Contents Interagency Policy StatementsInteragency policy statements providing guidance on safe and sound practices of credit underwriting and administration have existed for many years. More recently, however, the agencies, both individually and jointly, have issued guidance targeted more specifically at credit card lending.24 In January 2003, the Board, the FDIC, the OCC, and the OTS jointly issued guidance in response to concerns that certain industry practices were inappropriate, particularly with respect to creditline management, minimum payments, negative amortization, workout and forbearance programs, and various reporting requirements related to income recognition and loss allowances. For example, the agencies stated in the guidance: "Competitive pressures and a desire to preserve outstanding balances have led to a general easing of minimum payment requirements in recent years" (p. 3) and "In many cases, reduced minimum payment requirements in combination with continued charging of fees and finance charges have extended repayment periods well beyond reasonable time frames" (p. 4).25 The guidance specifically addressed these concerns and clarified supervisory expectations regarding account management, risk management, and loss allowance practices with respect to credit card lending. For example, the guidance stated that "When inadequately analyzed and managed, practices such as multiple card strategies and liberal line-increase programs can increase the risk profile of a borrower quickly and result in rapid and significant portfolio deterioration."26 Since issuing this guidance, the regulatory agencies have continued to monitor individual banking organizations carefully and, in cases where their practices have fallen short of supervisory expectations, have addressed those concerns in the ongoing examination process. Another issue arising in the administration of consumer credit information is the risk of identity theft and information security breaches. In early 2001, the agencies issued guidance establishing standards for safeguarding customer information.27 Back to Contents Examiner Guidance and ProceduresThe federal and state banking agencies have developed examination guidance and procedures, embodied in examination manuals, to address the various risk management and control functions needed by banking organizations to manage their credit card portfolios in a safe and sound manner.28 The agencies also have examination procedures and programs to monitor the compliance of financial institutions with applicable consumer protection laws and regulations. The Federal Reserve's Commercial Bank Examination Manual describes the risks associated with different types of credit card programs and recommends methods each banking organization should use to administer its program in a safe and sound manner. The manual covers credit-line management, overlimit practices, minimum payment and negative amortization, workout and forbearance practices, methodologies and practices for income recognition and allowances for loan and lease losses, recovery practices, and re-aging.29 Examination procedures include the review of policies, procedures, and internal controls; they cover policy considerations, audit, fraud, account solicitation, predictive modeling, and credit-scoring processes. Examiners evaluate the potential for problems that could arise from ineffective policies, unfavorable trends, lending concentrations, or non-adherence to policies. Back to Contents Enforcement ActionsWhen a regulated banking organization falls short of supervisory expectations, supervisors communicate their concerns in official letters to the organization's board of directors. In some cases, supervisors have required banking organizations to take appropriate remedial action, sometimes enforced by formal supervisory enforcement actions. If banking agencies determine that a bank has inadequate risk-management practices or supporting risk infrastructure, or is conducting unsafe and unsound operations, or is violating the law, the agencies have the authority to issue cease and desist orders and to take other enforcement actions against the bank. In addition, the regulators are empowered to impose civil money penalties for violations of banking statutes and regulations. With these enforcement powers, the banking agencies have, among other things, targeted unfair and deceptive marketing practices and in some instances have required banks to make restitution to customers. In addition, state officials from time to time have taken action against banks for their marketing and lending practices. These supervisory actions have led the banking organizations involved to adopt more appropriate practices. Back to Contents ConclusionWhen financial institutions make loans, they face the likelihood that some borrowers will prove unwilling or unable to meet the required payments. Lenders cannot identify those borrowers in advance, so they must estimate the probability that any given borrower will not pay, segment borrowers according to those probabilities, and price the extension of credit accordingly. In recent years, the data on the financial behavior of those with consumer credit and the technology to analyze the data have improved. These gains have allowed creditors to better segment customers by risk and to expand their reach to consumers that may not have been eligible for credit in the past. Risk segmentation enables providers to price for risk, reduces cross-subsidization among groups of borrowers, and discourages higher-risk individuals from borrowing excessively. Consistent with risk segmentation, the data illustrate a diversity of delinquency and default experience for different segments of the population. However, despite the large expansion in the proportion of households with credit cards in recent decades, measures of debt payments relative to income show no signs of a rise in distress in the aggregate. Providers of revolving credit segment by risk at several stages: when they prescreen potential customers before sending solicitations; when they decide whether to extend credit and how much credit to extend; and when they periodically manage and assess customer accounts. Consideration of an existing or potential customer's ability to repay is a major aspect of these activities. Attention to risk, including the risk of nonpayment, is a fundamental requirement of safe and sound lending and is enforced by market discipline as well as by federal and state government supervisors. Over time, however, consumers' circumstances can change, often unexpectedly, and these changes may adversely affect their ability to manage the debts they have incurred. Data on bankruptcy filings indicate that most consumers filing for bankruptcy have accumulated consumer debt, and the proportion of households filing has broadly risen in tandem with the inflation-adjusted amount of revolving consumer debt per household. However, the decision to file for bankruptcy is complex and tends to be driven by household distress arising from unforeseen adverse events such as job loss, divorce, and uninsured illness. Federal and state financial institution supervisors closely monitor credit card lending for compliance with consumer protection laws and regulations and to safeguard the safety and soundness of the lending institutions. The agencies have examination procedures in place, and they issue supervisory guidance as warranted. When a regulated organization falls short of supervisory expectations, supervisors communicate their concerns in official letters to the organization's board of directors. In some cases, supervisors have required that lenders take appropriate remedial action, sometimes enforced by formal supervisory enforcement actions. Back to Contents Appendix: Section 1229 of the Bankruptcy ActHere is section 1229 of the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005. SEC. 1229. ENCOURAGING CREDITWORTHINESS.

Notes1. In this report, the term "consumer credit" refers to credit that is used by individuals for nonbusiness purposes and that is not collateralized by real estate or specific financial assets like stocks and bonds. Consumer credit includes auto loans, home-improvement loans, appliance and recreational goods credit, unsecured cash loans, mobile-home loans, student loans, and revolving consumer credit. This definition is consistent with the usage of the term by the Federal Reserve and other banking agencies when they collect data on credit use. Revolving consumer credit, the focus of this report, is a line of credit that customers may use at their convenience and that primarily consists of credit extended through the issuance of credit cards. Return to text 2. The full text of section 1229 is in the appendix. Return to text 3. Remarks of Senator Dianne Feinstein (1999), "Bankruptcy Reform Act of 1999," Congressional Record (daily edition), vol. 145, November 17, pp. S14669-71. Return to text 4. The Federal Reserve has supervisory responsibilities for state-chartered banks that are members of the Federal Reserve System, bank and financial holding companies, Edge and Agreement Act corporations, and domestic operations of foreign banking organizations. Return to text 5. The Federal Reserve Board is currently reviewing the disclosures on credit cards required under its Regulation Z (Truth in Lending Act). This review will consider whether the information consumers receive about the costs and terms of credit card accounts is sufficient to help them make sound decisions about credit card use. Return to text 6. The household debt service burden, or "debt service ratio" as the series tracked by the Federal Reserve is named, consists of estimated aggregate required payments on all mortgage credit and revolving and nonrevolving consumer credit held by households as a percentage of the aggregate after-tax income of all households (www.federalreserve.gov/releases/housedebt). Return to text 7. Brian K. Bucks, Arthur B. Kennickell, and Kevin B. Moore (2006), "Recent Changes in U.S. Family Finances: Evidence from the 2001 and 2004 Survey of Consumer Finances," Federal Reserve Bulletin, vol. 92, pp. A1-A38. Return to text 8. The three largest credit reporting agencies are Equifax, Experian, and Trans Union Corporation; more information is in Robert B. Avery, Raphael W. Bostic, Paul S. Calem, and Glenn B. Canner (2003), "An Overview of Consumer Data and Credit Reporting," Federal Reserve Bulletin, vol. 89 (February), pp. 47-73. Return to text 9. The default experiences reported in the surveys pertain to all credit, not only revolving consumer credit (Bucks, Kennickell, and Moore, "Recent Changes in U.S. Family Finances," p. A35). Return to text 10. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2005), The Profitability of Credit Card Operations of Depository Institutions (108 KB PDF), annual report submitted to the Congress pursuant to section 8 of the Fair Credit and Charge Card Disclosure Act of 1988 (Washington: Board of Governors, June). Return to text 11. Notably, however, when asked the same question about themselves as opposed to about others, only about 15 percent answered affirmatively. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2004), Report to the Congress on Further Restrictions on Unsolicited Written Offers of Credit and Insurance (463 KB PDF) (Washington: Board of Governors, December), pp. 45-46. Return to text 12. Robert B. Avery, Gregory E. Elliehausen, and Arthur B. Kennickell (1987), "Changes in Consumer Installment Debt: Evidence from the 1983 and 1986 Surveys of Consumer Finances," Federal Reserve Bulletin vol. 73 (October), p. 769, table 9. Return to text 13. Further details are in Kathleen W. Johnson (2005), "Recent Developments in the Credit Card Market and the Financial Obligations Ratio," Federal Reserve Bulletin, vol. 91 (Autumn), pp. 473-86. Return to text 14. Michelle J. White (1998), "Why Don't More Households File for Bankruptcy?" Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, vol.14 (October), pp. 205-31. Return to text 15. David B. Gross and Nicholas S. Souleles (2002), "An Empirical Analysis of Personal Bankruptcy and Delinquency," Review of Financial Studies, vol. 15 (Spring), pp. 319-47. Return to text 16. Kartik Athreya (2004), "Shame As It Ever Was: Stigma and Personal Bankruptcy," Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Economic Quarterly, vol. 90 (Spring), pp. 1-19. Return to text 17. Scott Fay, Erik Hurst, and Michelle J. White (2002), "The Household Bankruptcy Decision ," American Economic Review, vol. 92 (June), pp. 706-18. Return to text 18. Li Gan and Tarun Sabarwal (2005), "A Simple Test of Adverse Events and Strategic Timing Theories of Consumer Bankruptcy," NBER Working Paper Series 11763 (Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, November). Return to text 19. Theresa Sullivan, Elizabeth Warren, and Jay Lawrence Westbrook (1989), As We Forgive Our Debtors: Bankruptcy and Consumer Credit in America (New York: Oxford University Press); Elizabeth Warren and Amelia Warren Tyagi (2003), The Two-Income Trap: Why Middle-Class Mothers and Fathers Are Going Broke (New York: Basic Books). Return to text 20. The path of delinquency rates on credit card loans at commercial banks shows no clear trend over time (figure 2). However, even if delinquency rates are constant, the number of delinquent accounts can be increasing as revolving consumer credit expands. Return to text 21. The National Association of Consumer Bankruptcy Attorneys surveyed 61,335 people who have undergone credit counseling, which is a step required under the new bankruptcy law before consumers can file for bankruptcy. Four out of five of those surveyed said they had to file because of job loss, large medical expenses, or the death of a spouse; 97 percent said they were unable to repay any of their debts (www.nacba.com). Return to text 22. A more extensive discussion of marketing and solicitation of credit cards is in Board of Governors, Further Restrictions on Unsolicited Offers. Return to text 23. The Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) regulates how creditors and insurers may use credit report information as the basis for sending unsolicited firm offers of credit or insurance to consumers. Subsection 604(c) of the FCRA designates the conditions for "furnishing reports in connection with credit or insurance transactions that are not initiated by the consumer." One of the requirements of a prescreening process is a notification system that enables consumers to elect to remove their names from prescreened solicitation lists, typically referred to as "opt out" rights. A more extensive discussion of opt-out provisions is in Board of Governors, Further Restrictions on Unsolicited Offers. Return to text 24. Among the subjects covered by relevant statements of guidance issued jointly by the Board, the FDIC, the OCC, and the OTS in recent years have been account management and loss allowances in credit card lending and issues in subprime lending. The Board distributed each of these interagency statements under a Supervision and Regulation (SR) Letter (issued by the Board's Division of Banking Supervision and Regulation to banking supervision staff at the Board and the Reserve Banks as well as to banking organizations supervised by the Board), as follows: SR 03-1, "Account Management and Loss Allowance Methodology for Credit Card Lending" (January 8, 2003); SR 01-4, "Subprime Lending" (January 31, 2001); and SR 99-6, "Subprime Lending" (March 5, 1999) (available at www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/srletters/). Return to text 25. The interagency guidance, "Credit Card Lending: Account Management and Loss Allowance Guidance," was distributed by the Board under SR Letter SR 03-1. Return to text 26. "Credit Card Lending: Account Management and Loss Allowance Guidance," p. 2. Return to text 27. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and Office of Thrift Supervision (2001), "Interagency Guidelines Establishing Standards for Safeguarding Customer Information and Rescission of Year 2000 Standards for Safety and Soundness," joint final rule, Federal Register, vol. 66 (February 1), pp. 8616-41; and Federal Reserve Board, SR Letter SR 01-11 (2001), "Identity Theft and Pretext Calling" (April 26). Return to text 28. Examples of such examination procedures and programs are in the booklets Credit Card Lending and Retail Lending Examination Procedures, in the OCC's Comptroller's Handbook. Also refer to the following OCC Advisory Letters: Guidance on Unfair or Deceptive Acts or Practices (OCC AL 2002-3), Credit Card Practices (OCC AL 2004-10), and Secured Credit Cards (OCC AL 2004-4). Return to text 29. "Re-aging refers to the removal of a delinquent account from normal collection activity after the borrower has demonstrated over time that he or she is capable of fulfilling contractual obligations without the intervention of the bank's collection department" (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Commercial Bank Examination Manual, Washington: Board of Governors), section 2130.1, p. 5. Return to text |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||