Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

2010 Annual Report to the Congress on the Presidential $1 Coin Program

Submitted to the Congress pursuant to section 104 of the Presidential $1 Coin Act of 2005

June 2010

Background

Pursuant to section 104 of the Presidential $1 Coin Act of 2005 (Public Law 109-145), the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System is required to assess and submit an annual report to the Congress on the remaining obstacles to the efficient and timely circulation of $1 coins; to assess the extent to which the goals of consultations with industry representatives, the vending industry, and other coin-accepting organizations are being met; and to provide such recommendations for legislative action as the Board may determine to be appropriate.

Recent Activities and Feedback from Depository Institutions

Since our 2009 annual report, the Federal Reserve Banks (the Reserve Banks) distributed nearly 300 million James Polk, Zachary Taylor, Millard Fillmore, and Franklin Pierce Presidential $1 Coins, satisfying depository institution demand.1 To facilitate this successful distribution, the Federal Reserve continued to refine the Presidential $1 Coin Program based on stakeholder input and experiences with previous Presidential $1 Coin releases. The Federal Reserve held meetings with the depository institutions with the largest cash volumes and with community bankers, as well as with armored carrier representatives, to gather feedback about demand and potential obstacles to the circulation of $1 coins.2

At these meetings, industry representatives indicated that the Presidential $1 Coin Program had worked very well, that the coins were easy to order, and that our communication about program dates and changes was effective. Participants indicated that transactional demand for $1 coins has not increased since the start of the program and that overall demand continues to come primarily from collectors. Most meeting participants did not believe that demand would increase significantly for future coin releases, with the possible exception of the coins commemorating the most popular former Presidents.

In the 2009 annual report, we reported that some depository institutions suggested that we lengthen the current pre-release staging period (during which banks can order and receive the coins but cannot release them to the public) from two weeks to three, to allow more remotely located branches to have the coins on hand by the public release date. Depository institutions also indicated that shortening the post-release introductory period from four weeks to two would provide sufficient time to meet their customer demand. In response, we implemented a new special ordering period in the first quarter of 2010, beginning with the Millard Fillmore Presidential $1 Coin release in February.3 (See figure 1 below for diagrams of the previous and current special ordering periods.)

Since the change, depository institutions have indicated that the new ordering period has improved the ability of their remotely located branches to order and receive coins by the release date, while accommodating their customers’ ordering patterns. As reflected in table 1 below, depository institutions have generally placed more than 80 percent of the total orders for each new release during the first three weeks of the special ordering period. The new ordering period accommodates these orders before the official release date.

Depository Institution Demand Continues to Decrease

The Federal Reserve's experience with circulating commemorative coins other than $1 coins has differed significantly from our experience with $1 coins. In the early years of the 50 State Quarters program, in an effort to support the legislation, the Reserve Banks ordered more quarters than were necessary to meet demand and filled many depository institution orders with new coins rather than with available inventories of circulated quarters.4 The residual coins from each release, plus the excess quarters redeposited by depository institutions, created excessive inventories at the Reserve Banks. The Reserve Banks were able to reduce those inventories over time, however, because of significant, regular transactional demand for quarters.5

For previous $1 coin programs, the Reserve Banks encountered large excess inventories for much longer periods because demand was very low. The Presidential $1 Coin Program experience is consistent with those other $1 coin programs. Dollar coin payments to circulation increased significantly in the first year of the program but have consistently declined since that time, while receipts from circulation have significantly increased. We have no reason to expect demand to improve. We also note that a 2008 Harris poll found that more than three-fourths of people questioned continue to prefer the $1 note.6

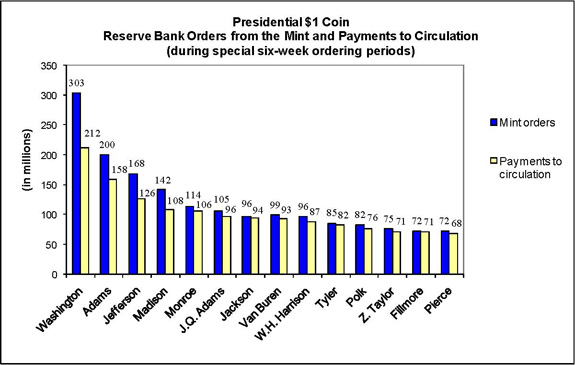

The Reserve Banks have studied detailed payment and inventory data for previous Presidential $1 Coin releases at the Reserve Bank offices and off-site coin terminals, supplemented these data with feedback from depository institutions about expected demand, and developed better forecasts for each successive release. The Reserve Banks have then actively managed inventories throughout the special ordering period for each coin, relocating coins around the country, as necessary, to meet demand. As figure 2 indicates, however, depository institution demand has continued to decrease.

Significant Growth of $1 Coin Inventories

Because we have not seen an increase in demand, the Federal Reserve Banks' $1 coin inventories have increased significantly over time, even though improved forecasting and ordering practices have reduced the number of residual coins at the end of each new release period. The Reserve Banks hold the residual coins as inventory at their offices and off-site coin terminals. Additionally and more significantly, depository institutions have re-deposited a significant number of excess $1 coins with the Reserve Banks.

As shown in figure 3 and table 2, previous $1 coin supplies, plus the excess $1 coins returned by depository institutions, elevated total Reserve Bank inventories of all $1 coins to almost $1 billion as of May 31, 2010, or about $932 million more than the Reserve Banks held before the start of the Program. Based on historical Presidential $1 Coin payments and receipts and current inventory growth trends, the Federal Reserve estimates that it could hold more than $2 billion in $1 coins by the time the program is expected to end. Because of vault storage constraints and insurance limitations at coin terminals, the Reserve Banks have been forced to spend resources in the past nine months to expand storage capacity to hold the excess $1 coins, with no perceivable benefit to the taxpayer. We expect that the Reserve Banks will need to continue to seek additional storage options to store the expected flowback of additional $1 coins through the end of the program.

Note: the United States Mint has indicated that it paid to circulation $88 million Native American $1 coins through its Direct Ship program in 2009 and $23 million in 2010 (as of June 17). The Mint also indicated that it has paid to circulation a total of $57 million Presidential $1 Coins via direct shipments since the start of the Presidential $1 Coin Program (as of June 17, 2010). These data are not included in the above Reserve Bank payments to circulation.

Note: the payments to circulation do not include the $1 coins that the United States Mint has issued directly into circulation. See note to figure 3.

Commemorative Circulating Coin Processes in Other Countries

To gain a broader perspective on the management of commemorative circulating coin programs, we explored the experiences of other countries. We found that other major industrial countries have implemented very different processes from the United States for issuing commemorative circulating coins. For example, the Eurosystem countries have regulations specifying that all commemorative circulating coins should be concentrated on the 2-euro coins. Eurosystem countries have also limited the quantities of these coins that these countries may issue.7 Other countries, such as Canada, limit the issuance periods and continue to issue the traditional design simultaneously with the commemorative circulating coins. Some central banks (for example, the Bank of England and the Bank of Canada) are not involved in the distribution of commemorative circulating coins or do not accept the return of coins from depository institutions. These types of restrictions serve to minimize the number of excess coins produced by the mint or held by the central bank.

Native American $1 Coin Requirement

Our first annual report to the Congress on the Presidential $1 Coin Program included a recommendation for legislative action regarding the "Sacagawea design" $1 coin provision in the Act.8 The Congress later reduced the Sacagawea production requirement in the Presidential $1 Coin Act with the enactment of the Native American $1 Coin Act (Public Law 110-82). The revised Presidential $1 Coin Act, however, retains a quantitative requirement for the volume of Native American $1 Coins that the Secretary of the Treasury shall mint and issue. The Reserve Banks' depository institution customers, however, have indicated that they have experienced very little or no demand for Native American $1 Coins.9 Given the lack of evidence to date that the Presidential $1 Coin Program will stimulate demand for $1 coins as a broad-based transactional medium, the requirement that a specified minimum number of coins be minted and issued without regard to actual public demand will continue to result in production and storage costs to the taxpayer without any offsetting benefits.

Footnotes

1. The 2009 Annual Report to the Congress on the Presidential $1 Coin Program.Return to text

2. Beginning in 2008, the Federal Reserve and the United States Mint agreed to meet with their respective coin user groups through our normal channels each year of the program and share feedback as appropriate.Return to text

3. The "special ordering period" consists of the both the "pre-release staging period" before the United States Mint's public release date (when depository institutions can order the coins from the Reserve Banks but cannot provide them to the public) and the "introductory period" after the release date (when depository institutions can provide the coins to the public and can continue ordering from the Reserve Banks). Return to text

4. After the initial years of the 50 State Quarters Program, the Reserve Banks began to move to more centralized management of coin ordering and distribution, which resulted in improved forecasts of coin demand. In 2008, the Reserve Banks fully centralized coin management at the National Cash Product Office, located at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Return to text

5. Because of lower payments of quarters to circulation during the financial crisis, Reserve Banks’ quarter inventories increased significantly in 2008 and 2009; however, the Reserve Banks expect to work down those inventories as demand improves. Return to text

6. http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSN1435329120080414 ![]() Return to text

Return to text

7. The Eurosystem countries' regulations specify that quantities are limited to the higher of the following:

0.1 percent of the total 2-euro coins in circulation, or 5 percent of the total of 2-euro coins from the issuing country.

8. http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/RptCongress/dollarcoin/dollarcoin.htm Return to text

9. Because of the lack of significant demand from Reserve Banks' depository institution customers for Native American $1 Coins and the Reserve Banks' high inventories of $1 coins, the Reserve Banks are not ordering Native American $1 Coins from the United States Mint. As indicated in the footnote to figure 3, the Mint is issuing these coins directly to the public. The coins end up at the Federal Reserve, however, as the public deposits them with their depository institutions, which then deposit them with their Reserve Banks. Return to text