FEDS Notes

December 20, 2024

A Note on Gender Differences in Credit Card Limit Changes

Nathan Blascak and Anna Tranfaglia*

Credit cards are the most widely held consumer debt product in the United States. Over 191 million Americans have at least one account (Haughwout et al., 2022) and nearly half of those with a credit card revolve a balance on at least one of their accounts (Federal Reserve Board, 2024). For those individuals who have credit cards, the average total credit limit on those cards is approximately $29,000 (Blascak and Tranfaglia, 2023).

Previous research has documented that there are gender differences in credit card limits (Blascak and Tranfaglia 2023). However, less is known about whether these differences result from gaps in the initial line assignments when cards are opened, or if they result from differences in changes in card limits made over time for existing accounts. This note helps to fill this gap by examining if [1] changes in credit card limits on existing accounts differ by gender and [2] if there are gender differences in limit changes at different points in the credit cycle.

An individual's total credit card limit is a function of initial line assignments (from opening an account), and subsequent line increases or decreases.1 The majority of line changes are initiated by lenders, who change credit limits when managing credit card accounts.2 They commonly monitor credit bureau data for early warning signs of default risk or improved creditworthiness.3 Lenders may increase or decrease limits due to economic conditions, for retention, or for-profit motives. For example, between June 2008 and January 2010, lenders decreased the credit limits on existing credit card accounts by $405 billion (Herman, Kannan, Kaplan, and Mueller, 2023).

Using detailed credit bureau data for successful sole-applicant mortgage applicants, we show the existence of an unconditional gender difference in the magnitude of changes to existing credit limits. We focus on credit card limit changes that coincide with no changes to the total number of credit card accounts. That is, we focus on credit line increases (CLI) and credit line decreases (CLD) to established accounts, not changes to limits that arise from opening or closing credit card accounts.4 For CLIs, men's limit increases are $243 higher than women's, while for CLDs, women's decreases are $95 smaller than men's. However, when limit changes are calculated as a percent change from the previous month's total limit, this disparity disappears. We also show that while limit changes differ across the stages of the credit cycle, they do not differ significantly by gender in different periods. These results suggest that these credit line adjustments are not the primary contributor to gender differences in total credit card limits.

Data and Methodology

To analyze if there are gender differences in how credit limits change, we use a merged dataset from three different sources: successful mortgage applicant information from the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA), mortgage performance information from ICE McDash, and anonymized credit bureau information from Equifax Credit Risk Insight Servicing and ICE McDash (CRISM). The merged HMDA-ICE McDash-CRISM (HIMC) dataset contains information on 56 million different mortgages that were originated from 1992 to 2017. For each mortgage, we observe both borrowers and co-borrowers, their demographic characteristics, and their credit bureau information at a monthly frequency from June 2005 to December 2017.

To select our analytical sample, we follow the same methodology outlined in Blascak and Tranfaglia (2023) and take a random 5 percent sample of loans with only one applicant in the HIMC dataset for computational efficiency.5 We drop any observations where the sole-mortgage applicant is age 80 or older, missing gender, or has a missing year of birth from our sample. We also restrict our sample to all full years of data. On average, we observe an individual in the HIMC data for over 7 years.

In our data, individuals have an average of seven overall credit limit changes, with individuals at the 75th percentile having 10 overall limit changes. Since we're interested in what happens after a limit change, we transform our data so we can examine multiple limit changes across calendar time for each individual in our sample. We do this in two steps: first, for each individual, we identify each limit change event they experience. For each event, we require the individual to be present in the HIMC data for the 3 months prior and 6 months post-limit change. To clearly identify the effect of a limit change, we further restrict our sample of limit changes to those that do not occur within three months of another limit change. In other words, each limit change does not have another limit change that occurs in the three months before it; we place no restrictions on subsequent limit changes after each limit change event. For each limit change, we construct a new dataset that contains data three months prior to the change and the six months after the change. We then take each "event" and vertically concatenate them (i.e., "stack" them) to form a new analytical data set (Hollingsworth and Wing, 2024). Finally, since we are interested in examining the effect of limits changes to existing accounts, we restrict our sample to limit changes that coincide with no change to an individual's existing number of credit card accounts. The resulting dataset contains 5.9 million limit changes for 860,000 consumers from 2006-2017.

We summarize credit card limit changes for individuals in our sample in Table 1. In panel A, we see that the number of credit card limit changes that coincide with a constant number of accounts are similar across gender: after restricting our sample to changes to existing accounts, the average number of limit changes per individual is approximately 3.38. In panel B, we show that median limit change magnitudes favor men by $200 for limit increases, but favor women by approximately $100 for limit decreases. In panel C, we present the limit changes as a percent change from the previous month's limit. Despite the difference in levels in panel B, we can see that in percentage terms, these changes are very similar for men and women. It is important to note that among successful sole-applicant mortgage applicants, men have larger total credit card credit limits. This happens despite women having more credit card accounts, on average (Blascak and Tranfaglia 2023, Board of Governors, 2023).

Table 1. Count and Magnitude of Limits Changes Conditional on Number of Cards Remaining Unchanged, by Gender

Panel A: Number of Limit Changes

| Number of Limit Increases | Number of Limit Decreases | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Men | Women | Overall | Men | Women | |

| 25% | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Median | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 75% | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Mean | 2.01 | 2.01 | 2 | 1.37 | 1.37 | 1.37 |

Note: Authors' calculations using Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data, ICE McDash loan servicing data, and Equifax Credit Risk Insight Servicing ICE McDash data. Demographic information comes from the HMDA data. Limit changes in this table are restricted to those that do not coincide with a change in the number of card accounts.

Panel B: Magnitude of Limit Changes (in dollars)

| Magnitude of Limit Increases | Magnitude of Limit Decreases | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Men | Women | Overall | Men | Women | |

| 25% | 500 | 548 | 500 | -650 | -626 | -676 |

| Median | 1,500 | 1,500 | 1,300 | -2,076 | -2,095 | -2,000 |

| 75% | 3,000 | 3,000 | 2,650 | -5,500 | -5,500 | -5,380 |

| Mean | 2,287 | 2,390 | 2,147 | -4,075 | -4,191 | -3,929 |

Note: Authors' calculations using Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data, ICE McDash loan servicing data, and Equifax Credit Risk Insight Servicing ICE McDash data. Demographic information comes from the HMDA data. Limit changes in this table are restricted to those that do not coincide with a change in the number of card accounts.

Panel C: Magnitude of Limit Changes (percent change)

| % Change of Limit Increases | % Change of Limit Decreases | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Men | Women | Overall | Men | Women | |

| 25% | 4.20% | 4.30% | 4.10% | -3.70% | -3.60% | -3.75% |

| Median | 9.90% | 10.00% | 9.60% | -10.50% | -10.50% | -10.40% |

| 75% | 22.20% | 22.70% | 21.50% | -24.50% | -24.80% | -24.20% |

| Mean | 30.00% | 31.00% | 28.60% | -17.70% | -17.90% | -17.50% |

Note: Authors' calculations using Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data, ICE McDash loan servicing data, and Equifax Credit Risk Insight Servicing ICE McDash data. Demographic information comes from the HMDA data. Limit changes in this table are restricted to those that do not coincide with a change in the number of card accounts.

To show the effect of CLIs and CLDs on available credit during our period of study, we estimate the following simple nonparametric event study specification separately by gender and by type of limit change:

$$$$ Y_{it} = \alpha_{0} + \sum_{-3}^{6} \beta_{e} T_{e} +\lambda_{i} +\gamma_{t} +\epsilon_{it} $$$$

The vector $$ T_{e} $$ contains relative event time dummy variables, where event time $$e$$ refers to a month relative to the month of CLI or CLD $$(e=0)$$. Our omitted event time period is $$e=-1$$, the month before the limit change. $$ \lambda_{i} =$$ is an individual fixed effect and $$ \gamma_{t} $$ is a calendar time fixed effect. Our variables of interest $$ Y_{it} $$ are the total credit limit on all credit cards and the percent change in total limit relative to the previous month. By specifying our model in this way, we can examine the patterns in changes to total credit limits in the months after a CLI or CLD.

Results

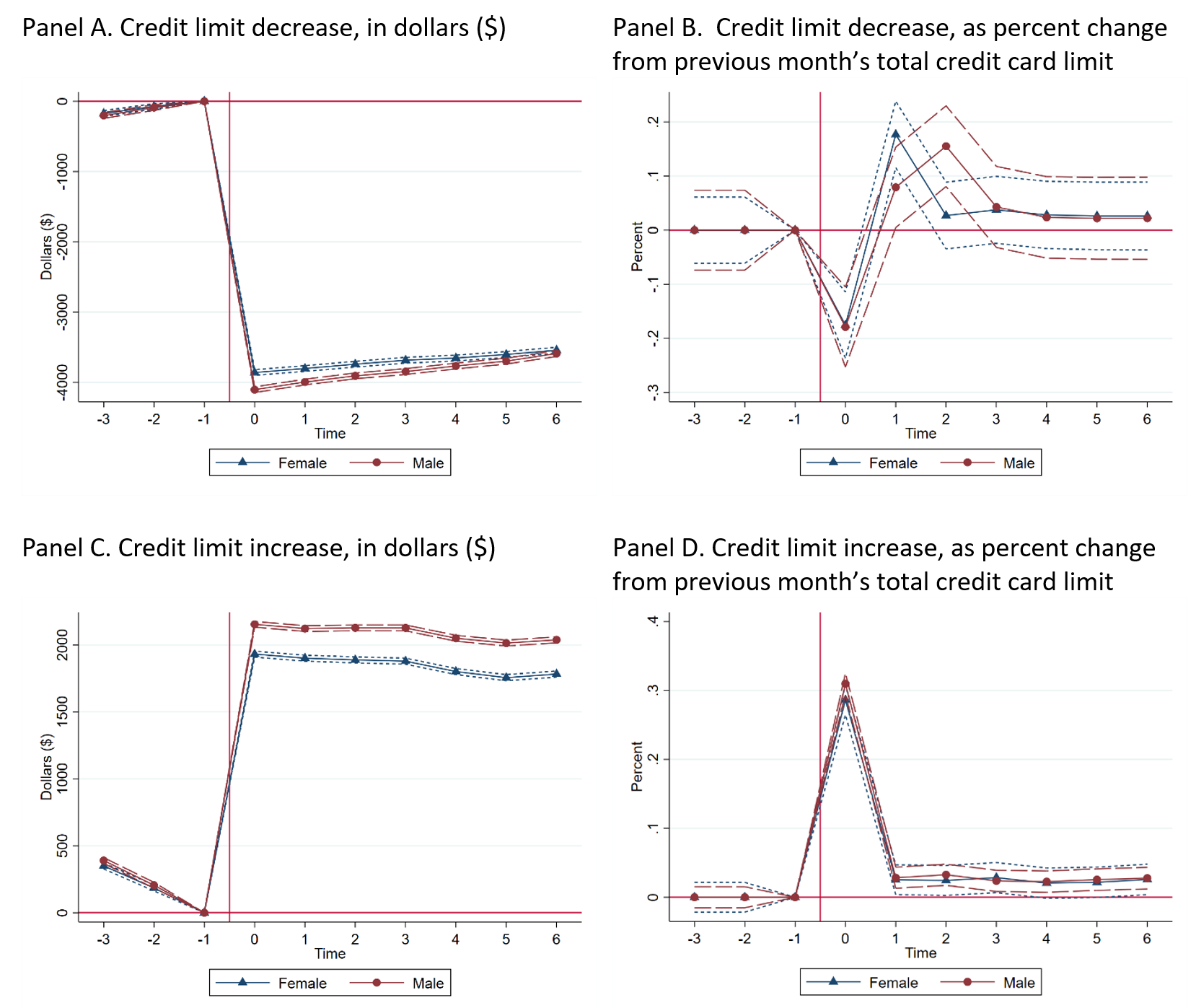

Results from estimating equation (1) are presented in Figures 1. Panel A of Figure 1 shows the magnitude of a CLD in dollars, while panel B shows the limit decrease as a percent of the previous month's total limit. For men in our sample, the average decrease is -$4,103, while for women the decrease is -$3,859. Despite the differences in levels in panel A, panel B shows that this decrease was the same for both men and women in percentage terms (approximately 18 percent). Panel C shows the average size of a CLI in dollars, while panel D shows the increase as a percent of the previous month's limit. The average CLI for men is $2,155 and for women it is $1,932. Similar to our results in panel B, when we look at limit increases in percent terms in panel D, there is no difference between genders. The difference in the results between levels and percent changes results are not surprising given the fact that men have larger credit card limits overall (Blascak and Tranfaglia, 2023).

Note: Authors' calculations using Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data, ICE McDash loan servicing data, and Equifax Credit Risk Insight Servicing ICE McDash data. Demographic information comes from the HMDA data. Dashed lines are 95 percent confident intervals for males, dotted lines are 95 percent confidence intervals for females. Time is measured in months. Percent in panels B and D is measured between 0 and 1. The vertical red line separates months before and after the limit change.

Panels A and C of Figure 1 also show that CLDs were less stable than CLIs. Six months following a limit decrease, the total credit card limit recovered on average by $515 for men and $317 for women (compared to the initial decrease). This is in comparison to CLIs, which remain relatively more stable in the six months after the change, with limits declining by approximately $130 for each gender. This difference in the dynamics is likely driven, in part, by individuals either electing to apply for and open new credit card accounts following a limit decrease, or receiving additional limit increases on other accounts, as one limit change decision can induce a separate line adjustment from the same or different issuer. Individuals experience 1.94 additional limit changes after an initial CLD versus 1.73 limit changes after a CLI.

Results Across the Credit Cycle

In the previous section, we aggregated all limit increases and decreases throughout our study period, but lenders may employ different credit line assignment regimes during recessionary periods and recovery periods. To examine if limit changes differ during different periods of the credit cycle, we follow Han, Keys, and Li (2018) and define April 2008 – April 2009 as the recessionary period of the credit cycle and May 2009 – December 2017 as the recovery period of the credit cycle and estimate Equation (1) for each period separately. In addition to splitting CLIs and CLDs by phases of the credit cycle, we also look at each gender separately, as lenders' underwriting and credit line adjustment strategies in each phase may affect each gender differently.

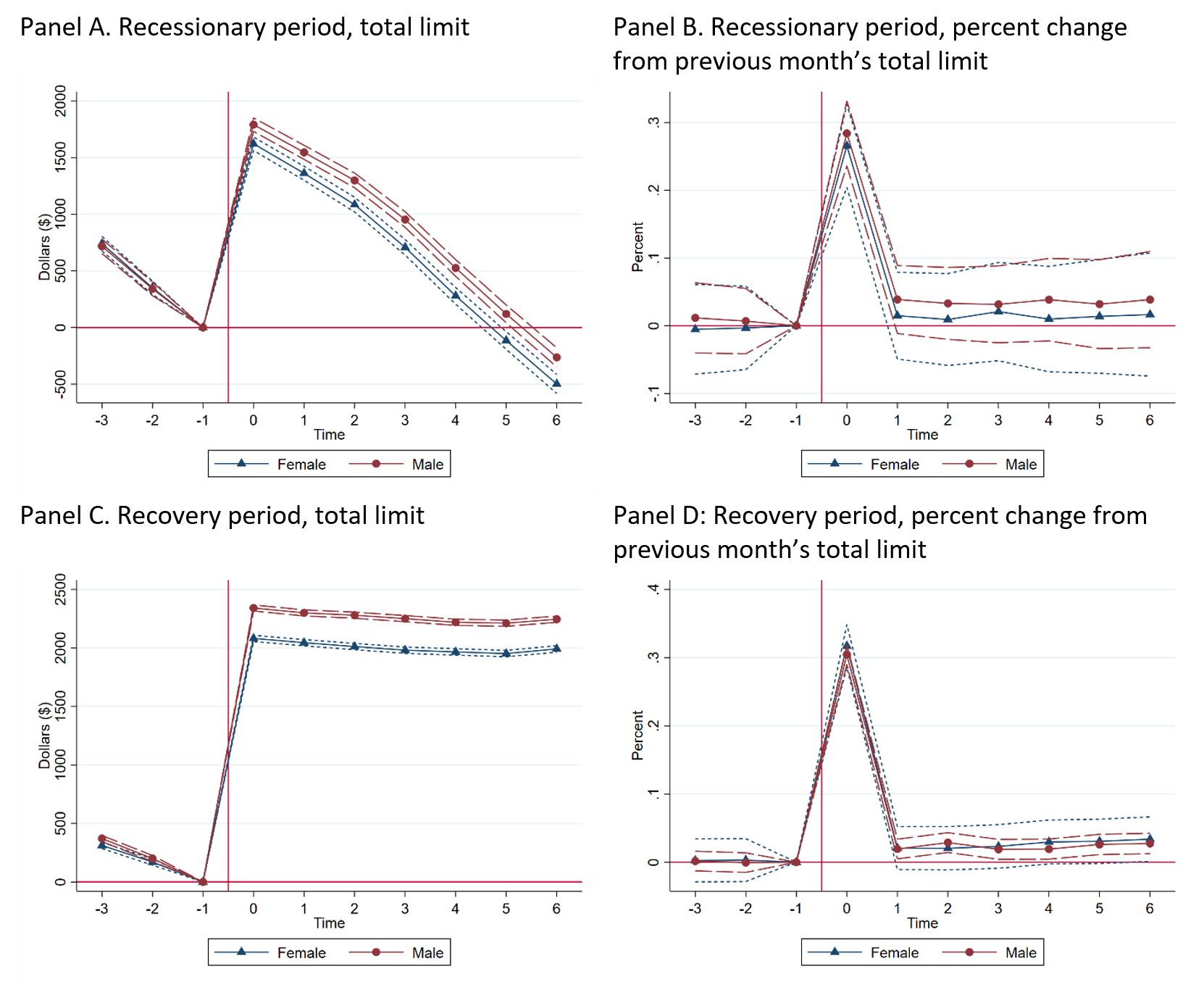

Figure 2 shows CLIs split out by gender for the recessionary and recovery periods of the credit cycle. Approximately 13.5 percent of all CLIs in our sample happen in the recessionary period, which is consistent with the proportion of calendar time our overall sample is in the recessionary period.6 CLIs differ in magnitude and dynamics by the part of the credit cycle they occur in. In panel A, we can see that during the recessionary period, limit increases are $1,791 and $1,622 for men and women, respectively. However, the magnitudes of the limit changes are larger for both men and women when they occur during the recovery phase of the credit cycle (Figure 2, panel C), with total limits increasing by $2,341 for men and $2,081 for women. In percent terms, the CLIs during the recessionary period are approximately a 29 percent increase (Figure 2, panel B) and the CLIs during the recovery period are a 30 percent increase (Figure 2, panel D).

Note: Authors' calculations using Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data, ICE McDash loan servicing data, and Equifax Credit Risk Insight Servicing ICE McDash data. Demographic information comes from the HMDA data. Dashed lines are 95 percent confident intervals for males, dotted lines are 95 percent confidence intervals for females. Time is measured in months. Percent in panels B and D is measured between 0 and 1. The vertical red line separates months before and after the limit change.

The dynamics after the credit limit increase also differ by the phase of the credit cycle. During the recessionary period (panel A), the limit increase is short-lived, with the average total limit decreasing over time, resulting in the bankcard limit being lower for both men and women six months after the limit change than prior to the CLI.7 During the recovery period (panel C) of the credit cycle, we can see that six months following a CLI, the average change in total credit limit is relatively unchanged compared to the initial increase in total limit in the first month following the adjustment. The asymmetry in dynamics between the two phases is due in part to the difference in the number of subsequent limit changes after the initial CLI. After the initial CLI, there are 1.82 additional limit changes during the recessionary period while there are only 1.19 additional limit changes during the recovery period.8 As was the case for our pooled results in Figure 1, if we look at the CLI and its subsequent changes in terms of percent change from the previous month's limit, there are no differences between men and women (panels B and D).

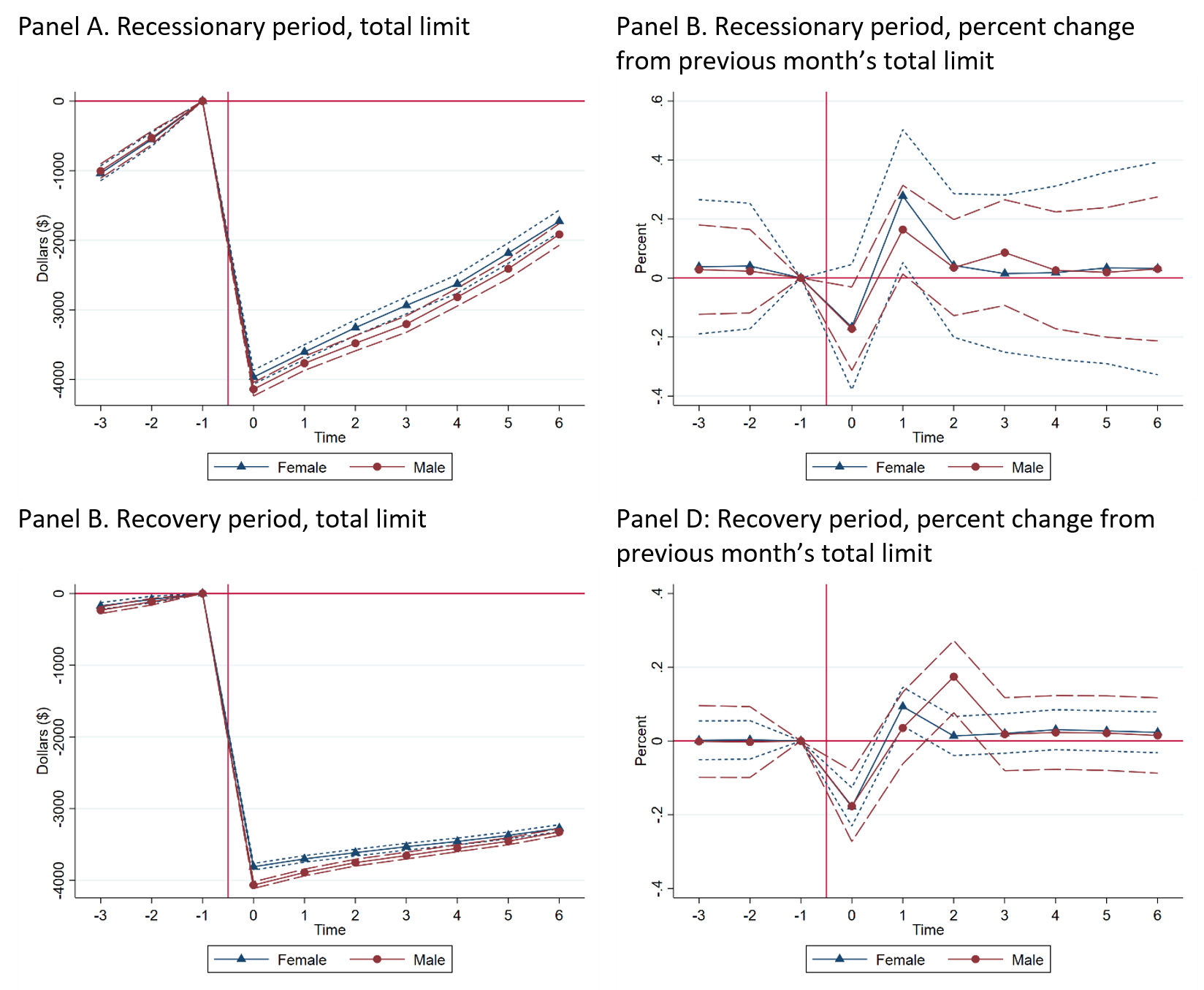

In Figure 3, we show CLDs for the recessionary and recovery periods of the credit cycle. CLDs were much more prevalent during the recessionary period than CLIs, with over 21 percent of CLDs occurring during this period (compared to 13.5% or CLIs). In panels A and C, we can see that the magnitudes of CLDs are similar for men and women in our sample whether they occur during the recovery or recession period. The magnitudes of the CLDs are not significantly different between men and women during the recession period (panel A). In panel C, we can see that men's total credit limits decline by more than they do for women as a result of a CLD during the recovery period. For both time periods, the initial CLD is an approximate 18 percent decline (Figure 3, panels B and D) from the previous month.

Note: Authors' calculations using Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data, ICE McDash loan servicing data, and Equifax Credit Risk Insight Servicing ICE McDash data. Demographic information comes from the HMDA data. Dashed lines are 95 percent confident intervals for males, dotted lines are 95 percent confidence intervals for females. Time is measured in months. Percent in panels B and D is measured between 0 and 1. The vertical red line separates months before and after the limit change.

Similar to the credit line increases, the dynamics over the following six months after a CLD differ by phase of the credit cycle. When credit limit decreases occurred during the recessionary period of the credit cycle, both men and women regained approximately half of the initial decrease within six months following the adjustment (panel A). However, as was the case for credit limit increases, cuts to credit card limits are more stable during the recovery period (panel C). This difference between phases of the credit cycle is partly due to the fact that there 1.92 additional limit changes after the initial CLD in the recessionary period and only 1.37 additional limit changes after the initial CLD in the recovery period.9 We also note that in percent change terms, there are no statistically significant differences between men and women for CLDs during either period of the credit cycle (panels B and D).

Summary

In this note, we use a unique dataset that combines mortgage application information with credit bureau data to examine if there are gender differences in credit card limit adjustments. Both overall, and during recessionary and recovery periods, men experience larger changes to existing credit limits in absolute magnitude. However, when measured as a percent change from the previous month's total credit card limit, the magnitude of the adjustments is not significantly different between men and women. Overall, these results suggest that gender differences in credit limits at card origination play a more important role in explaining the gender gap in total credit card limits than gender differences in subsequent limit changes. There are many possible mechanisms that could explain gender differences in limits at origination, and our previous work in Blascak and Tranfaglia (2023) provides a discussion of some the potential channels that could result in these differences.

References

Blascak, N. and Tranfaglia, A. (2023). "Gender Differences in Credit Card Limits: Evidence from Sole Mortgage Applicants." Working Paper.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (2024) "Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2023".

Fulford, S., & Stavins, J. (2024). "Income and the Card Act's Ability‐To‐Pay Rule in the US Credit Card Market." Working Paper.

Han, S., Keys, B.J. and Li, G., (2018). "Unsecured credit supply, credit cycles, and regulation." The Review of Financial Studies, 31(3), pp 1184-1217.

Haughwout, A., Lee, D., Mangrum, D., Scally, J., and van der Klaauw, W. (2022). "Balances Are on the Rise—So Who Is Taking on More Credit Card Debt?" Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics.

Herman, L., Kannan, A., Kaplan, J., and Mueller, A. (2022, November 15). "Credit Card Line Decreases (PDF)." Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

Wing, C., Freedman, S.M., and Hollingsworth, A. (2024). "Stacked Difference-in-Differences." NBER Working Paper.

* Blascak: Consumer Finance Institute, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia; Tranfaglia: Federal Reserve Board. We thank Bob Hunt, Julia Cheney, Jeff Larrimore, Larry Santucci, and Tom Akana for helpful comments. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, the Federal Reserve Board, or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors. No statements here should be treated as legal advice. Return to text

1. Limit changes to existing bankcard accounts can be either initiated by the consumer (asking the lender for more (or less) credit) or the lender (in response to changes to the consumers' credit report or from updated income information from the consumer). Return to text

2. Fulford and Stavins (2024) find that income (level) reported during account application, prior to account opening, does not affect credit line adjustments to existing accounts, even though income is an important factor in initial credit line assignment. Rather, other factors affect banks' credit decisions for existing borrowers, such as any update to income (including decreases) as these might signal cardholder engagement. Return to text

3. Credit reporting companies offer products to issuers that monitor and identify specific behavior that may be related to credit risk, such as delinquencies or credit score changes. Return to text

4. In our dataset, we have aggregate bankcard limit and aggregate number of bankcard accounts. Return to text

5. For mortgages with co-applicants, we have CRISM data for each individual applicant of that mortgage. However, the data do not identify which individual is the applicant and which individual is the co-applicant in the HMDA data. Therefore, we drop co-signed mortgages from the data because, although we know the gender of the applicant and the co-applicant for each mortgage, we cannot accurately assign the applicant/co-applicant gender variables in the HIMC sample. Return to text

6. Given that our sample runs from April 2008 to December 2017, and we define the recessionary period of the credit cycle as April 2008 to April 2009, we have 13/117 = 11% of months in our data occur during the recessionary period. Return to text

7. Since we do not have any restrictions for the 6 months following the limit change in our event study design, the decline could be explained by credit limit decreases or individuals closing accounts. Return to text

8. Additionally, while the number of new card openings after the initial CLI are similar in the recessionary and the recovery period (0.286 vs 0.233, respectively), the number of card closures after the initial CLI differ substantially between phases (0.45 vs. 0.19). Return to text

9. Less than 30 percent of the subsequent limit changes after the initial CLD are due to additional card closures. Return to text

Blascak, Nathan, and Anna Tranfaglia (2024). "A Note on Gender Differences in Credit Card Limit Changes," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, December 20, 2024, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3652.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.