FEDS Notes

September 23, 2024

Dealer Balance Sheet Constraints Evidence from Dealer-Level Data across Repo Market Segments

Lia Chabot, Paul Cochran, Sebastian Infante, Benjamin Iorio1

On November 12, 2024, footnote 16 was updated to remove an inaccurate measure of Treasury net issuance.

The continued growth of U.S. Treasury issuance has garnered interest in understanding dealers' ability to intermediate the U.S. Treasury market. These trends have spurred various efforts to measure the degree to which dealer balance sheet constraints—broadly defined as restrictions on the overall size of an intermediary's balance sheet—can affect the intermediation of the Treasury market. In this note, we present a novel measure based on individual dealer-level data that isolates the compensation dealers receive for intermediating overnight Treasury repurchase agreements (hereafter, "repos") across repo market segments. Our balance sheet constraint measure, coined the Cross-Market Treasury Repo (CMTR) spread, is the cross-sectional average of dealer-level repo rate spreads between centrally cleared bilateral (henceforth, "DVP") reverse repo and uncleared tri-party (henceforth, "tri-party") repo, which are two important segments of U.S. repo markets that bring together cash investors and leveraged Treasury market investors via dealers.2 Because Treasury repo intermediation involves negligible risk but is balance sheet intensive, dealers' compensation for intermediating between these markets is a plausible proxy for the balance sheet cost to do so. Moreover, because Treasury repo allows intermediaries to source and distribute funds and collateral, this activity is critical for Treasury market intermediation, underscoring why our measure captures balance sheet constraints related to Treasury market making.

To accurately isolate individual dealers' balance sheet constraints when intermediating Treasury repo, we match repo market activity across different data sets and focus on trades that are motivated by borrowing and lending cash. We apply this methodology to the nine largest dealers active in U.S. Treasury markets who are affiliated with bank holding companies (BHCs) or intermediate holding companies (IHCs). 3 These dealers account for a large fraction of Treasury market activity and are arguably the marginal investors across repo market segments. We calculate an individual dealer's volume-weighted average overnight reverse repo rate in the DVP market—excluding trades that are motivated by sourcing collateral—and volume-weighted average repo rate in the tri-party market. We calculate the spread between these rates and take the cross-sectional average to estimate our balance sheet constraint measure.

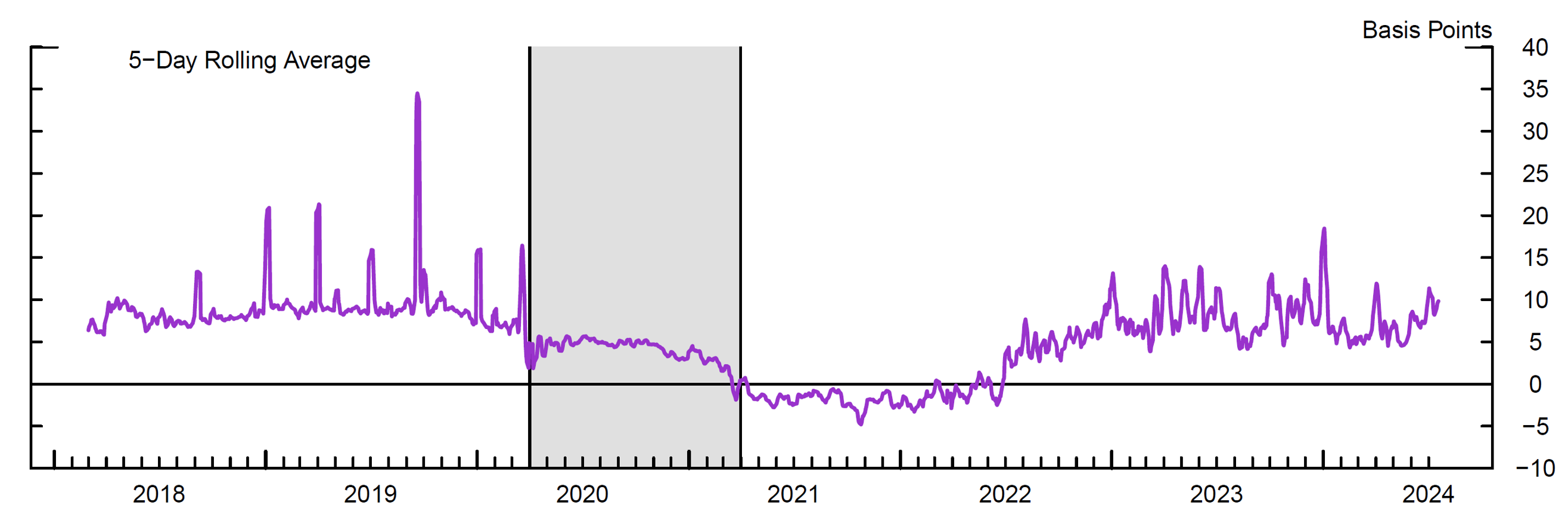

Figure 1 shows the five-day moving average time series of the CMTR spread from February 2018 to July 2024. The series shows sharp increases on month- and quarter-end dates which is consistent with dealers' incentive to scale back their activities because of increased balance sheet costs on regulatory reporting dates, an activity known as window dressing. Interestingly, between March 2021 and April 2022, the CMTR is slightly negative. This coincides with the period during which short-term funding rates were at the offering rate at the Federal Reserve's Overnight Reverse Repurchase Facility (ON RRP) and ON RRP balances were elevated, implying that repo rates in the tri-party market could not be pushed down further, making the CMTR negative.4,5 The negative spread throughout this period suggests that when short term rates are effectively at zero, intermediaries have limited ability to raise funds at lower rates.6 However, outside of that period, we observe that the CMTR averages around 7 bps, but varies significantly over time. Moreover, the CMTR averages 4 bps in the period supplementary leverage ratios (SLRs) increased due to the exclusion of reserves and Treasury securities from the calculation, decreasing the cost to expand balance sheets to intermediate funding (shaded area). Given that this spread measures the effective compensation dealers receive from intermediating Treasury repo—where the economic motive is to disburse cash—we argue that the CMTR spread is a precise measure of dealer balance sheet costs.

To validate our measure, we compare the CMTR to another well-known measure of dealer balance sheet costs related to repo intermediation, namely, the GCF and tri-party repo spread. Conceptually, the CMTR and the GCF-tri-party repo spread both measure the compensation to intermediate funds from the general tri-party market to repo borrowers that cannot access that market directly. However, over recent years, the GCF market has shrunk considerably, raising questions about the informativeness of the GCF-tri-party spread. Moreover, it is a measure based on market wide activity. We show that the CMTR and the GCF-tri-party repo spread track each other quite closely in the time series, but their levels and changes have materially different summary statistics. Because the CMTR is based on dealer-level data that isolates individual dealer level activity, the CMTR is a more accurate measure of balance sheet constraints. Our analysis of the cross-section of individual spreads that make up the CMTR indicates the compensation to intermediate repo is uniform across dealers; however, there is a fair degree of heterogeneity in their participation.

Background on U.S. Repo Markets and the Role of Dealers

Repos are collateralized loans backed by securities which allow market participants to raise secured funding or borrow securities for a fixed duration.7 Treasury market intermediaries, such as large creditworthy primary dealers, rely on repo markets to source and distribute funds and securities. These contracts support dealers' market making activities and enhance market liquidity for the underlying Treasury securities. The role of repo is especially important for dealers' participation in the Treasury market where, in the last few years, 68% of the Treasury securities they accessed were via reverse repos and 94% of their secured borrowing with Treasury collateral were via Treasury repos.8 The intensive use of repos in dealers' intermediation activity indicates that Treasury repos account for a large share of their overall balance sheet and that costs associated with balance sheet capacity may affect their behavior in these markets.

Therefore, dealers would need to be compensated for allocating large fractions of their balance sheets to intermediate repo by only accepting a relatively lower rate when borrowing funds and a higher rate when lending funds. This insight is particularly salient for Treasury collateral given the limited risk associated with Treasury repo intermediation, limiting the scope for risk premia to play a meaningful role in determining the spread, suggesting that the spread between rates captures the balance sheet cost associated with this activity.

To accurately measure transactions that lead to an increase in the usage of a dealer's balance sheet capacity, it is important to measure dealer activity across different segments of U.S. repo markets. In effect, intermediating cash between lenders and borrowers that can only access specific repo market segments unequivocally increases a dealer's balance sheet—an activity known as matched book repo. In the U.S., the repo market contains two submarkets, tri-party and bilateral, each with different types of market participants. In this note, we specifically focus on two subsegments of these markets: tri-party and DVP. With this focus, we can filter the data to capture the economic incentives to participate in these markets, and thus, gauge the costs dealers face when intermediating across Treasury repo markets.

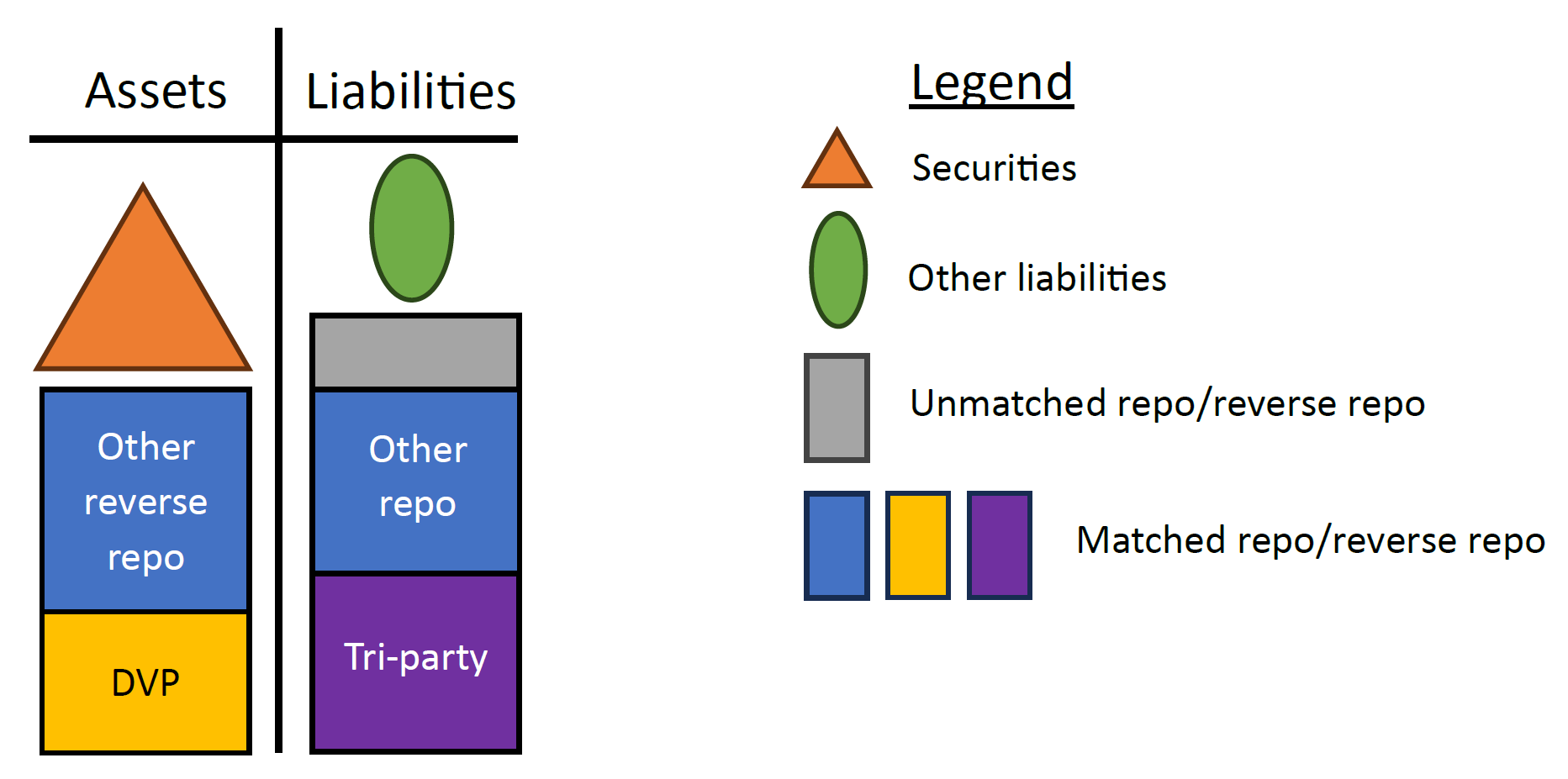

In the tri-party market, dealers enter repos with cash investors, such as money market funds. Dealers use the cash they receive from these transactions to finance their own securities holdings, and to a greater extent, reverse repos in other market segments. Most of the dealers' cash lending via repo is in the DVP and the bilateral uncleared markets. Dealers' matched book activity across the tri-party and DVP markets brings together cash-rich investors that want to lend cash and leveraged investors that want to borrow cash, represented by the purple and yellow bars in Figure 2. The figure underscores that matched book repo across market segments can significantly increase balance sheet size as the dealer re-uses the collateral to intermediate secured funding. Consequently, this activity increases balance sheet costs associated with size.

In principle, dealers can net down their matched book activity under certain conditions to reduce the balance sheet allocation to matched book activity.9 In fact, a large share of dealers' netting activity occurs in the DVP market, which is centrally cleared by the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation (FICC) that acts as both the borrower and lender. However, netting does not occur in the tri-party repo market because the market's cash lenders, such as money market funds, are one-directional traders and only lend. With no ability to net down transactions, the un-netted borrowing increases balance sheet costs related to size.

Thus, by borrowing from cash-rich investors in the tri-party market and lending in the DVP market, dealers engage in a balance sheet intensive and low yielding intermediation activity. The nature of this intermediation makes dealers' balance sheets sensitive to internal balance sheet constraints, such as value-at-risk, and external regulatory restrictions, such as the non-risk-weighted capital requirement from Basel III: the SLR.10 In theory, if a dealer is closer to breaching their constraints their ability to intermediate is limited.11 We hypothesize that these constraints, in turn, incentivize dealers to increase the price they charge for their intermediation services, which can be measured by the difference in lending and borrowing rates. Thus, from this perspective, we would expect the spread between borrowing in the tri-party market and lending in the DVP market to be the profit from a dealer expanding its balance sheet to intermediate cash. In equilibrium, this difference captures the intermediaries' balance sheet costs.

Methodology to Calculate the CMTR

To provide insights into the magnitude of dealers' balance sheet costs, we aim to calculate each individual dealer's repo spread across markets. Importantly, we focus on transactions that are likely driven by the incentive to intermediate cash. To do so, we synthesize four repo data sets that come from different sources and capture different aspects of repo market activity across market segments. Conceptually, measuring the difference between reverse repo lending rates and repo borrowing rates is a simple calculation. In practice, however, it involves matching repo market activity across different repo data sets and isolating trades that are motivated by borrowing and lending cash. The first hurdle is challenging because data sets across repo market segments have different reporting requirements, making it difficult to accurately identify a specific intermediary across each data set. Specifically, we use data from the FR 2052a, FR 2004, DVP data, and Matching data.12 The first two data sets allow us to capture total overnight Treasury repo market activity, which gives us the ability to match dealer activity across repo market segments. The second two data sets contain transaction-level data from which we can calculate an individual dealer's weighted average borrowing and lending rate in repo markets. The second hurdle is excluding trades that are motivated by sourcing collateral rather than cash, which would contaminate the interpretation of the spread. We overcome these challenges by (1) matching individual dealers' repo volume across various repo data sources to leverage different data fields across data sets, and (2) focusing on repo activity in the DVP repo market that is included in the Secured Overnight Funding Rate (SOFR) calculation which attempts to isolate transactions driven by borrowing and lending cash.

We correctly identify the dealer-level transactions across data sets that report multiple legal entities associated with the same consolidated entity. Our strategy consists of manually matching aggregate Treasury repo volumes across market segments—which are reported in different data sets—of the nine largest dealers active in U.S. repo markets.13 We focus our attention on overnight repos of nominal Treasury securities and remove sponsored transactions.

Because we want to measure the profitability of intermediating repo across segments, we exclude trades that may be driven by the incentive to source collateral rather than funds. Repos for specific-issue collateral with rates below those for general collateral repos are said to be trading "special." These transactions are not motivated by the incentive to intermediate cash, and thus would capture other considerations beyond balance sheet costs. We use the same methodology as the Federal Reserve Bank of New York's (FRBNY's) calculation of the SOFR to remove these transactions, the so-called SOFR trim.14

We also exclude trades between affiliated entities under the same holding company in the tri-party market which may be part of the firm's liquidity management practice. This exclusion is also used in FRBNY's SOFR calculation. We also apply standard filters like excluding forward settlements and keeping "open" trades which are economically similar to overnight transactions.

Finally, we calculate each dealer's volume-weighted overnight repo and reverse repo rates and then take the spread between the DVP reverse repo rate and tri-party repo rate for each dealer. Our aggregate dealer balance sheet cost measure, the CMTR, is the simple average of the nine dealers' spreads which reflect the marginal cost of increasing the size of their balance sheet.

Main Findings

Through our matching procedure we are able identify each dealer in our sample across all our repo data sources. Specifically, in the tri-party market, aggregate volumes of our nine dealers in the FR 2052a and Matching data align closely with their primary dealers' FR 2004 totals. In the bilateral market, we can get a close match between cleared bilateral trades in DVP and FR 2004. Because historically the FR 2052a did not differentiate between cleared and uncleared bilateral trades, aligning cleared volumes in DVP and FR 2004 was impossible. However, the form revision adopted in May 2022 required identification of centrally cleared transactions. Since June 2023 aggregate cleared volumes across all three data sets align, while aggregate uncleared volumes differ slightly due to internal transactions being defined at the dealer-level in FR 2004 and the BHC- and IHC-level in FR 2052a.15 Matching volumes across the FR 2004 and FR 2052a confirms we identify the appropriate reporting party across data sets. The nine dealers in our sample account for roughly 68% of total primary dealer Treasury repo volumes. When aggregated, the volumes in the bilateral and tri-party markets line up but differences at the firm level do exist.

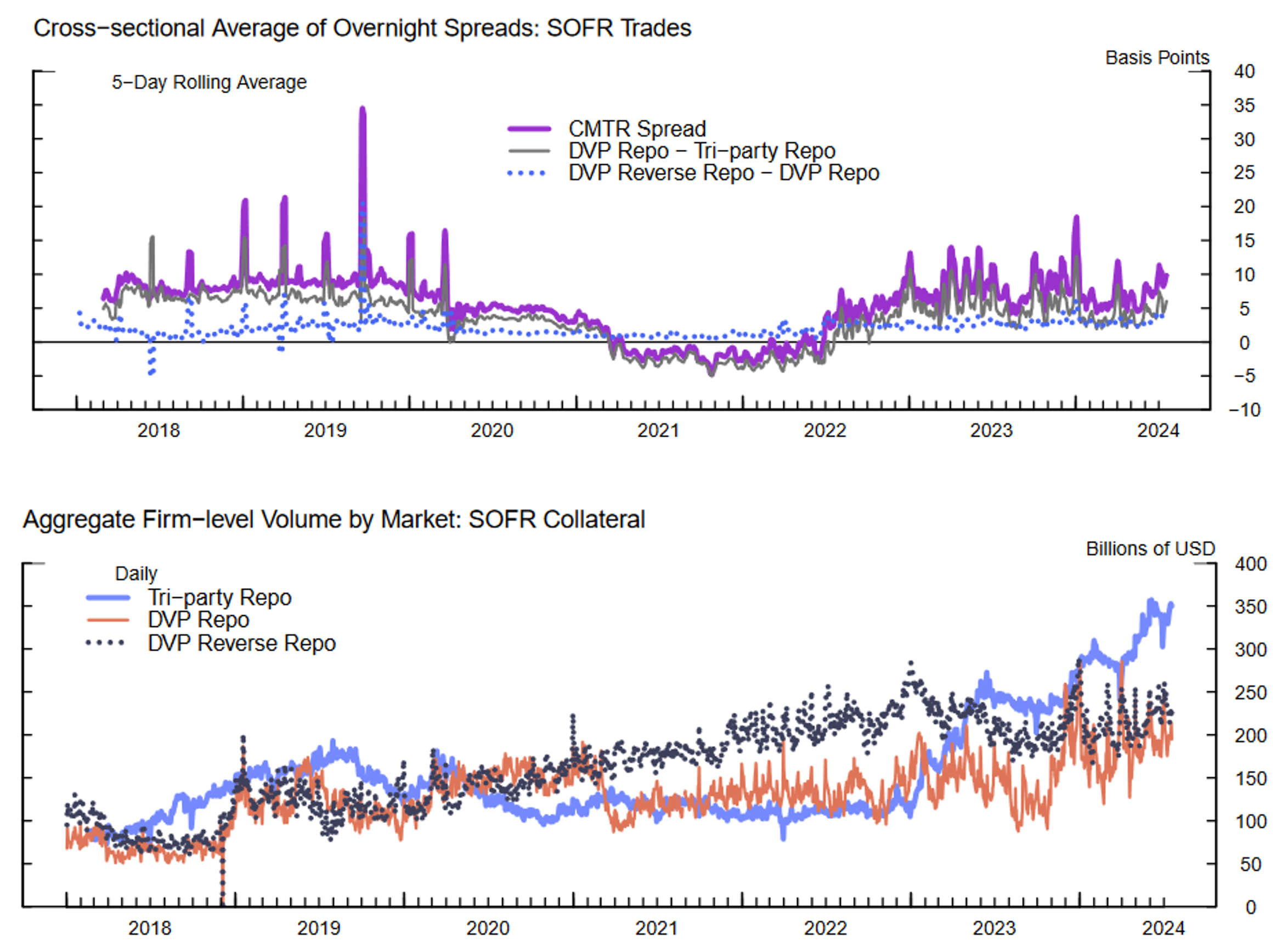

Having an approximate match for volumes in different repo market segments, we turn to calculating the repo spread across segments, the five-day rolling averages of which are shown in the top panel of Figure 3. The spread between DVP repo and tri-party repo (gray line) shows that borrowing in DVP is relatively more expensive than borrowing in tri-party. As a result, dealers primarily borrow in tri-party markets and lend in bilateral markets. The spread between DVP reverse repo and tri-party repo (purple line), is our CMTR spread and represents dealers' profit from cross-market intermediation. As dealers' balance sheets become constrained, the CMTR spread should increase as dealers demand more compensation to intermediate funding. As shown in the top panel of Figure 3, the CMTR spread is more profitable than within-market intermediation (DVP reverse repo and DVP repo, blue line). However, spreads between reverse repo and repo transaction within the DVP market do not accurately capture an increase in balance sheet costs because many of these transactions can be subject to netting.

The bottom panel of Figure 3 shows the repo volumes that make up our calculation. SOFR-eligible tri-party repo volumes (light blue line) make up roughly 51% of our sample's aggregate firm-level tri-party repo, and SOFR eligible DVP repo (orange line) and reverse repo (dark gray line) volumes make up roughly 73% of our sample's aggregate firm-level DVP volumes each. The sizable share activity in the tri-party and DVP repo market segments suggests that an important fraction of dealers' repo activity can be attributed to intermediating repo across markets.16 Repo volumes from our SOFR eligible sample make up roughly one fourth of the total transaction volume used to calculate SOFR.

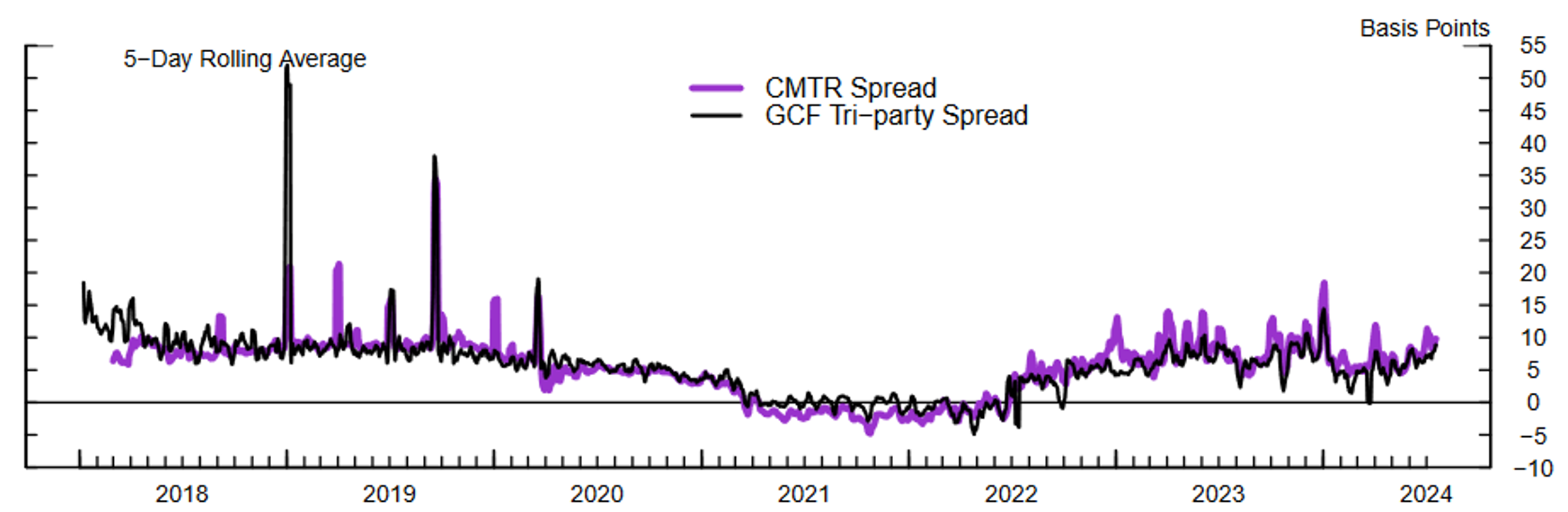

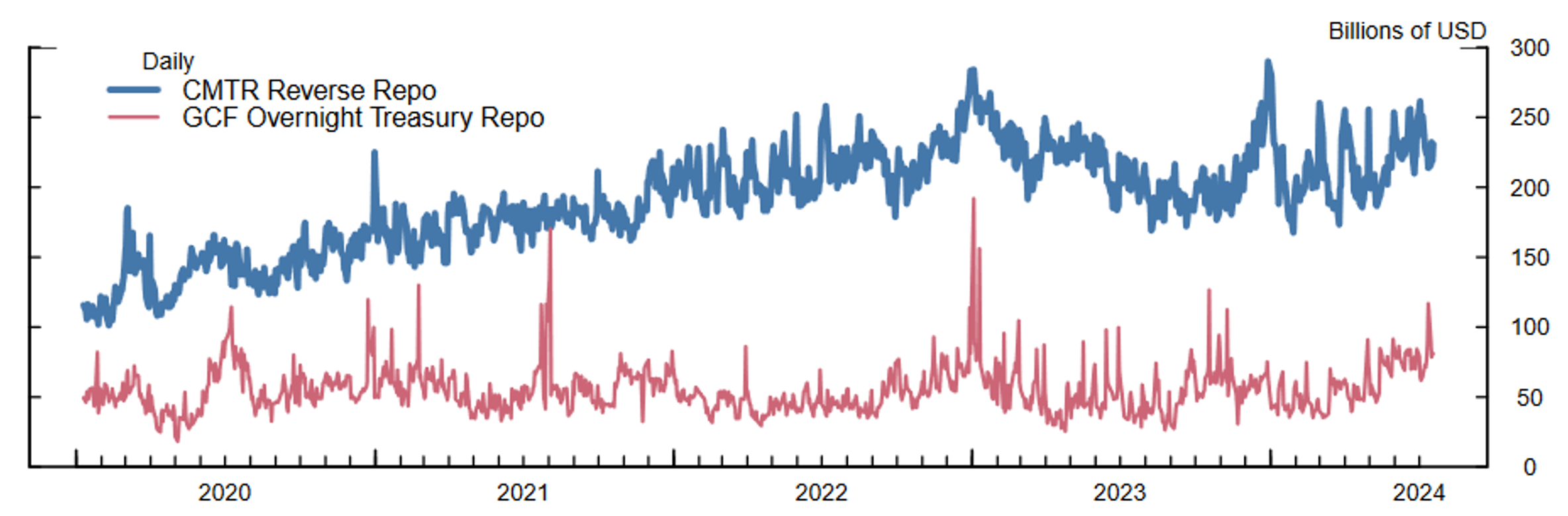

In Figure 4, we test the validity of our measure of balance sheet costs—the CMTR spread—by comparing it against the spread between GCF repo and tri-party repo.17 These two series track each other quite closely, with few differences in scale over the sample period. In fact, both series turn negative between March 2021 and July 2022, which we attribute to the ON RRP's effect on tri-party lending at the time.18

Even though the CMTR spread and GCF tri-party spread exhibit similar trends, there are differences over the sample period. Table 1 provides summary statistics of both measures for comparison. The daily versions of each series are moderately correlated, with a correlation coefficient of 0.58. Most notably, Table 1 shows that the GCF tri-party spread is much more volatile with a standard deviation 1.5 times that of the CMTR spread and a maximum more than three times that of the CMTR. This volatility may be driven by the low trading volume in the GCF market, making the GCF spread more susceptible to outliers.

Table 1: CMTR and GCF Tri-party Spread Summary Statistics

| Mean (bps) |

Standard Deviation (bps) | Min (bps) |

Max (bps) |

N | Correlation of Levels | Correlation of Changes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily | CMTR Spread | 5.58 | 5.46 | -5.62 | 69.95 | 1,583 | 0.58 | 0.19 |

| GCF Tri-party Spread | 5.53 | 7.39 | -33.4 | 219.9 | 1,590 | |||

| 5-Day Rolling Average | CMTR Spread | 5.61 | 4.61 | -4.8 | 34.49 | 1,535 | 0.82 | 0.41 |

| GCF Tri-party Spread | 5.54 | 4.84 | -4.9 | 51.96 | 1,574 | |||

| Weekly Average | CMTR Spread | 5.71 | 5 | -4.2 | 34.89 | 339 | 0.56 | 0.51 |

| GCF Tri-party Spread | 6.04 | 12.37 | -3.86 | 219.9 | 339 | |||

In Figure 5, we compare aggregate Treasury repo volumes used in our CMTR spread and the GCF tri-party spread. The reverse repo volumes that make up the CMTR spread (blue line) are over four times the size of the volumes used in the GCF tri-party spread (red line). This observation suggests that the CMTR spread is a more robust measure of dealer balance sheet constraint. Specifically, given that our measure isolates cash intermediation via repo at the dealer-level, it is more likely to capture the costs of said activity.

Details on Individual Dealer Activity

So far we have focused on the average intermediation spread across the nine largest dealers; however, the dispersion across individual dealer activity is instructive to understand how representative our measure may be. Table 2 shows the cross-sectional summary statistics of the individual components of the CMTR spread (panel A) and aggregate volumes of reverse repo activity (panel B).

Table 2: Cross-sectional Summary Statistics

Panel A

Make Full Screen| CMTR Spread | Mean (bps) |

Standard Deviation (bps) |

1st Percentile (bps) |

99th Percentile (bps) |

Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 5.25 | 8.33 | -6.45 | 34.78 | N = 12323 |

| Between | 2.18 | 2.81 | 10.04 | n = 9 | |

| Within | 8.11 | -8.97 | 30.64 | T-bar = 1369.22 |

Panel B

Make Full Screen| DVP Reverse Repo Volume | Mean (Billions of USD) |

Standard Deviation (Billions of USD) |

1st Percentile (Billions of USD) |

99th Percentile (Billions of USD) |

Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 20.3 | 17.98 | 0.06 | 69.71 | N = 13150 |

| Between | 14.97 | 1.64 | 42.28 | n = 9 | |

| Within | 10.46 | -6.47 | 49.6 | T-bar = 1461.11 |

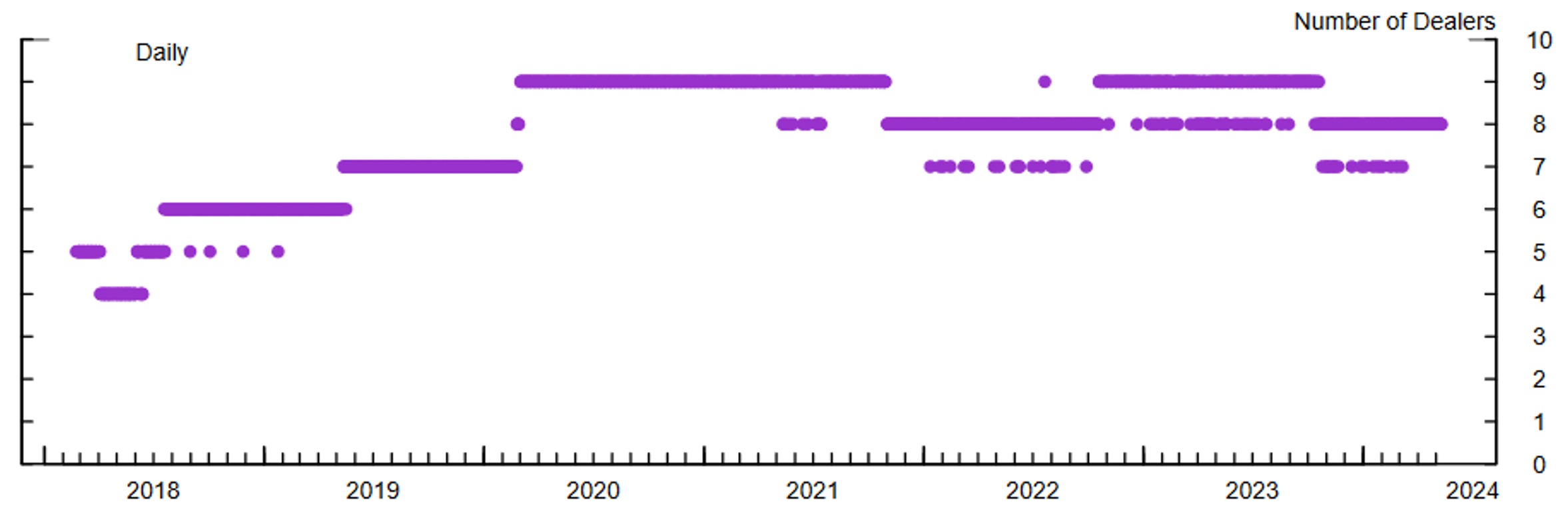

Panel A indicates the dispersion of intermediation spreads across dealers is relatively small (2.18 basis points), and the majority of the variation comes across time (8.11 basis points). Panel B indicates that there is a fair amount of dispersion in reverse repo volumes in the DVP market, which highlight the heterogeneity in dealer participation. Figure 6 shows that the number of dealers that make part of the CMTR varies over time. Together these observations suggest that while the intensity of intermediation activities across dealers does vary, the compensation they receive is fairly stable.

References

Afonso, Gara, Marco Cipriani, and Gabriele La Spada. Banks' Balance-Sheet Costs, Monetary Policy, and the ON RRP. Federal Reserve Bank (FRB) of New York Staff Report, No. 1041, 2022. URL https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4308896

Cochran, Paul, Sebastian Infante, Lubomir Petrasek, Zack Saravay, and Mary Tian. Dealers' Treasury Market Intermediation and the Supplementary Leverage Ratio. Finance and Economics Discussion Series (FEDS), Federal Reserve Board of Governors, 2023. URL https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3341.

Favara, Giovanni, Sebastian Infante, and Marcelo Rezende. Leverage Regulations and Treasury Market Participation: Evidence from Credit Line Drawdowns. SSRN, 2022. URL https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4175429

He, Zhiguo, Stefan Nagel, and Zhaogang Song. Treasury Inconvenience Yields During the COVID-19 Crisis. Journal of Financial Economics, 143:57-79, 2022. URL https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.05.044

Infante, Sebastian, Lubomir Petrasek, Zack Saravay, and Mary Tian. Insights From Revised Form FR2004 Into Primary Dealer Securities Financing and MBS Activity. Finance and economics discussion series (FEDS), Federal Reserve Board of Governors, 2022. URL https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3182

1. We thank David Bowman, Lubomir Petrasek, Zeynep Senyuz, and Min Wei for helpful comments and suggested edits. The views of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System or of any other person associated with the Federal Reserve System. Return to text

2. Throughout this note, we use "DVP" to refer to the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation's (FICC's) Delivery-versus-Payment (DVP) Repo Service. We also use "tri-party" to refer to uncleared tri-party transactions as opposed to FICC's General Collateral Finance (GCF) Repo Service which is the centrally cleared segment of the tri-party repo market. Return to text

3. A BHC is any company (including a bank) that has direct or indirect control of a bank. An IHC is a company established or designated as one by a foreign banking organization with average U.S. non-branch assets of $50 billion or more. BHC is defined in section 2(a) of the Bank Holding Company Act (12 U.S.C. § 1841(a)) and section 225.2(c) of the Board's Regulation Y. IHC is defined under subpart O of the Federal Reserve Board's Regulation YY. The BHCs and IHCs in our sample are Bank of America, Barclays, Citigroup, Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, Morgan Stanley, and Wells Fargo. Return to text

4. The ON RRP is a short-term funding facility available to eligible counterparties and is a supplementary policy tool to help control the federal funds rate and keep it in the target range set by the FOMC. More information can be found at: https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/overnight-reverse-repurchase-agreements.htm. Return to text

5. The start of this period coincides with the lifting of the exemption from the SLR rule, which increased dealers balance sheet intermediation costs and pushed activity out of private repo to the ON RRP facility. Return to text

6. Between March 2021 and March 2022 the tri-party general collateral repo rate (TGCR) and the ON RRP administered rate averaged 3.8 and 3.6 bps, respectively. Return to text

7. A reverse repo is a repo from the perspective of the cash lender. In other words, it is when a market participant lends cash in exchange for a security as collateral. Return to text

8. See Cochran et al (2023) and Infante et al (2022) for estimates on the shares of dealers' Treasury cash and repo market activity concentrated in Treasury collateral. Return to text

9. Banks subject to leverage regulations can net the regulatory size of their balance sheet if their repos and reverse repos are (a) with the same counterparty, (b) have the same maturity, and (c) are carried out over the same settlement systems. Return to text

10. He, Nagel, and Song (2022) found that the SLR restricted dealers from absorbing the Treasury supply shock seen in March 2020. Return to text

11. See Favara, Infante, and Rezende (2022) for a study on the effects of the SLR on dealers' Treasury market participation. Return to text

12. The DVP data is a Treasury repo reference rate data set from the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation (FICC), the central clearing counterparty of the cleared bilateral repo market segment. The Matching data is a repo rate data set from tri-party clearing banks which identifies the total amount borrowed by different reporting parties in the tri-party market. Return to text

13. The volumes across data sets do not match perfectly due to reporting errors, changes in surveys, and the nature of data collection. Return to text

14. In the SOFR calculation, DVP repo transactions with rates below the 25th volume-weighted percentile rate are removed from the distribution of DVP repo data each day. For more information on the FRBNY's SOFR calculation methodology, see https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/reference-rates/additional-information-about-reference-rates#tgcr_bgcr_sofr_calculation_methodology. Return to text

15. This new reporting of FICC transactions was mandated to U.S. dealers in May 2022 and foreign dealers in October 2022. The lag before volumes align across data sets may be due to respondents adjusting to the new form: https://www.federalreserve.gov/reportforms/formsreview/fr%202052a%20omb%20ss_final.pdf. Return to text

16. In early 2023, repo volumes in the tri-party market increased rapidly due to the reduction in net T-bills issuance, which made tri-party repo more attractive for money market investors. Return to text

17. Previous literature has used this spread to capture dealer regulatory balance sheet constraints. See for example He, Nagel, and Song (2022). The GCF repo rate series is downloaded from Bloomberg and the triparty rate series is downloaded from FRBNY. Return to text

18. ON RRP rate sets a floor for tri-party borrowing rates. When there was excess cash in the system in early 2021, uptake in the facility was high and the ON RRP rate floor was binding. This artificially maintained tri-party borrowing rates above DVP lending rates, resulting in a negative CMTR spread. Once cash in the system reached an equilibrium in mid-2022, ON RRP volumes flattened out, borrowing and lending rates became more competitive, and DVP lending rates rose above tri-party borrowing rates, leading to a positive CMTR spread. Return to text

Chabot, Lia, Paul Cochran, Sebastian Infante, and Benjamin Iorio (2024). "Dealer Balance Sheet Constraints: Evidence from Dealer-Level Data across Repo Market Segments," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, September 23, 2024, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3598.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.