FEDS Notes

January 19, 2024

Does the Ability to Work Remotely Alter Labor Force Attachment? An Analysis of Female Labor Force Participation

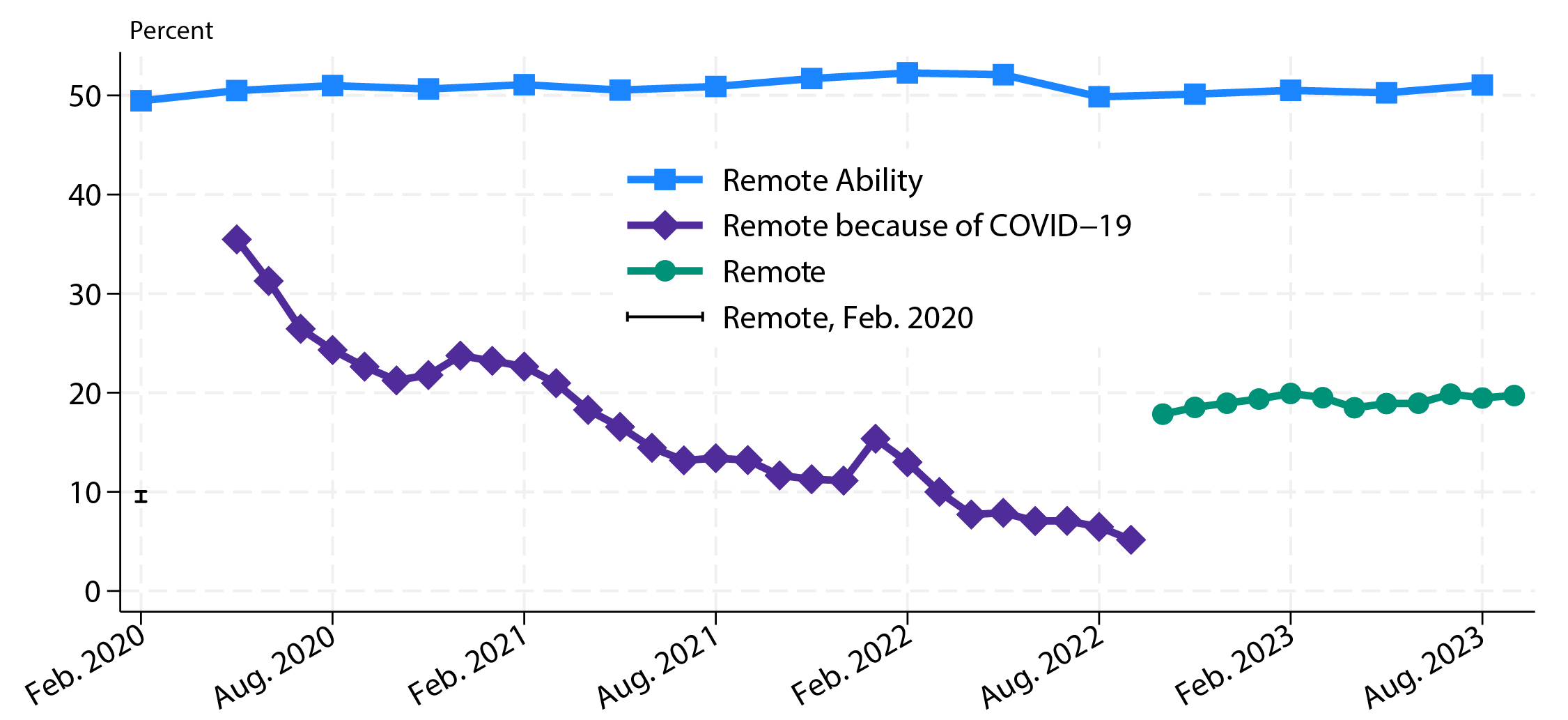

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, a large share of the employed switched to remote work. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)'s Current Population Survey (CPS), almost 40 percent of workers were working remotely in May 2020 because of the pandemic (figure 1, purple line), adding to the evidence from other individual- and firm-level surveys.2 Remote work because of the pandemic gradually declined over subsequent months, representing 5.2 percent of employment by September 2022. As the definition of remote work because of the pandemic became too narrow, starting in October 2022, the BLS added new supplemental questions to CPS that focused on remote work more generally and compared current trends with remote work as of February 2020.3 According to the responses to the new supplemental questions, in recent months, almost 20 percent of workers reported working remotely for all or part of the survey reference week (green line). Recent usage of remote work appears well above February 2020 levels (black line), which were between 9 and 10 percent.

Note: Comparison between the share of employment in occupations with the ability to work remotely and reports of remote work from survey respondents.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration (USDOL/ETA).

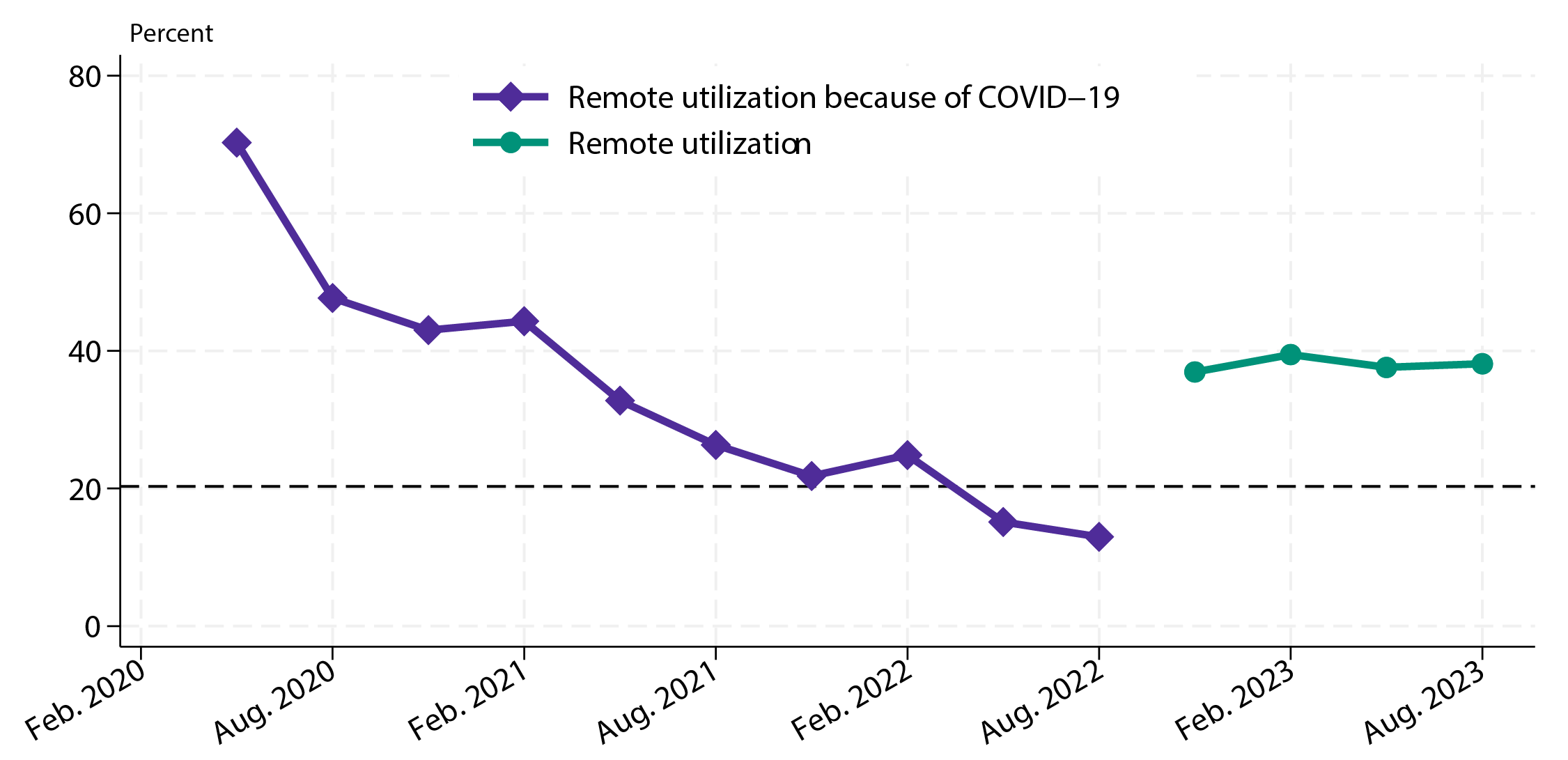

While remote work peaked in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic and was, in recent months, almost double the levels observed in February 2020, those usage indicators remain well below measures of remote ability. In particular, figure 1 also compares CPS definitions of remote work with a measure of remote ability built upon Montenovo et al. (2020).4 Even at the peak of remote usage in May 2020, the gap between ability and actual remote work remained more than 10 percentage points. To more quickly contrast notions of remote ability and current usage, I propose a measure of remote utilization, defined as the ratio of the share of employment performing remote work to the share of jobs characterized by remote ability. Figure 2 identifies the behavior of remote utilization over my sample period. With limited variation in remote ability over short time horizons, remote utilization mostly reflects actual usage of remote work: It reached 40 percent in recent months (green line), about double the pre-pandemic levels (dashed line).

Note: Ratio of remote usage to remote ability. Black dashed line represents remote utilization as of February 2020.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and USDOL/ETA.

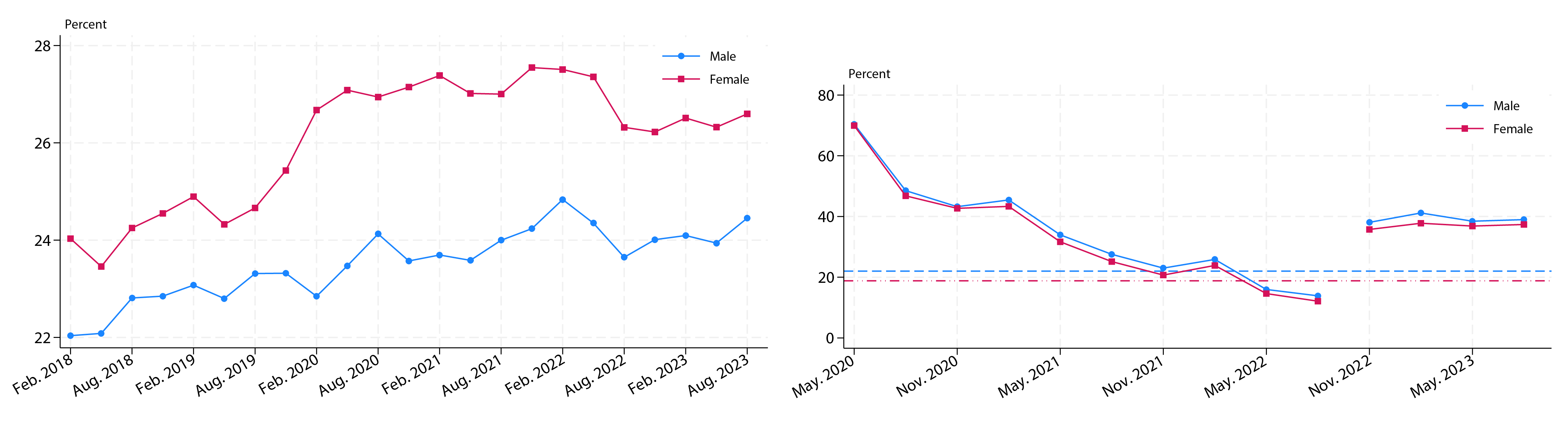

Did access to remote work and changes relative to the pre-pandemic period influence the labor market outcomes of different demographic groups? This note focuses primarily on differences by gender. To start with, figure 3 illustrates the features of remote ability and remote utilization across males and females. Historically, women have been employed in occupations with higher remote ability; a larger gap in ability between females and males opened up at the end of 2019 (left panel). The differences in ability explain why female remote utilization is slight below that of males (right panel); differences in utilization—of 3 percentage points (pp) as of February 2020—however, have become less pronounced over time.

Figure 3a (Left Figure)

Note: Share of employment by gender in occupations that can be performed remotely.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and USDOL/ETA.

Figure 3b (Right Figure)

Note: Utilization of remote work by gender. Data through September 2022 refer to remote work because of the COVID−19 pandemic; data after October 2022 refer to remote work more generally. Dashed line denotes pre−pandemic utilization for males, while dash−dotted line is for females.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and USDOL/ETA.

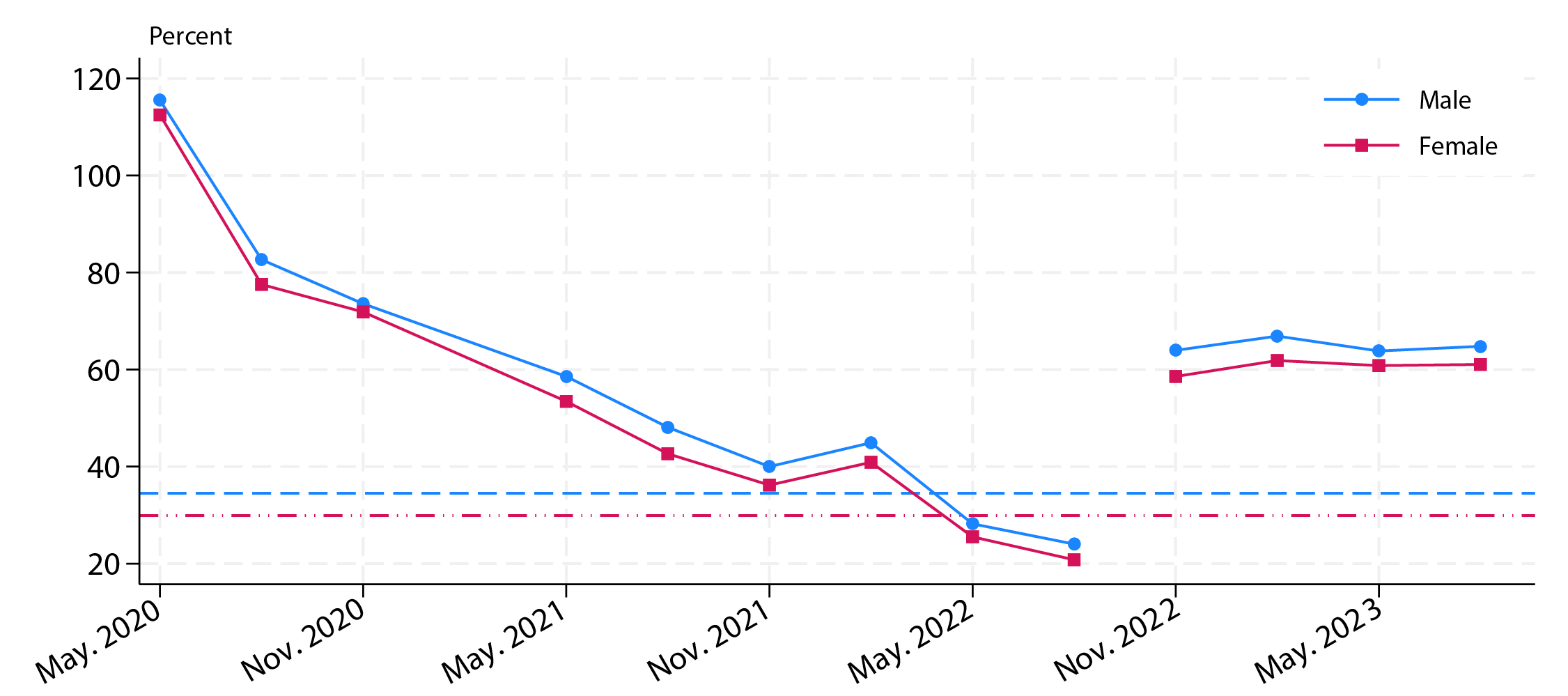

Prime-age individuals have relied more on remote utilization. As shown in figure 4, levels of remote utilization are 20 pp higher than for the overall working population. Two other features of this graph deserve more attention. First, remote utilization for both male and female prime-age individuals was above 100 percent in May 2020; this issue could either reflect the relative rigidity of the measure of remote ability—in contrast with some short-term adaptability of jobs that could not generally be performed remotely and that adopted "remote attributes" in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic—or missing observations.5

Note: Utilization of remote work by gender for prime−age individuals. Data through September 2022 refer to remote work because of the COVID−19 pandemic; data after October 2022 refer to remote work more generally. Dashed line denotes pre−pandemic utilization for males, while dash−dotted line is for females.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and USDOL/ETA.

Second, as with the entire working-age distribution, gaps in utilization have shrunk over the post-pandemic period, from 5 pp to a little over 3 pp. Interestingly, the gaps in utilization for prime-age groups are a touch higher than those for all employees.

While the analysis of figures 3 and 4 highlights changes in remote utilization and in access to remote work for prime-age women, I now move to address the labor market implications of those changes. As measures of utilization are available only over a short sample period, I'll focus on how access to remote work has shaped the labor market prospects of prime-age women relative to prime-age men. Langemeier and Tito (2022) underscore that there are general labor market benefits associated with occupations that can be performed remotely; here, I will dissect the differential impact by gender. My baseline analysis links labor market flows to my preferred measure of remote ability and observable demographics of the group of interest,

$$$$ y_{i,j \rightarrow k,st} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 Female_{it} + \beta_2 Remote Ability_{st} + \beta_1 Female_{it} Remote Ability_{st} + \varepsilon_{it} \ (a)$$$$

where $$ y_{i,j \rightarrow k,st} $$ is an indicator equal to 1 if individual $$i$$ changes labor market status $$ (j \rightarrow k ) $$ at time $$ t, Female_{it} $$ is a dummy equal to 1 for prime-age women, and $$ Remote \ Ability_{st} $$ denotes occupations where, according to the O*Net classification, the usage of e-mail, memo, and phone is important or very important.6 In particular, I linked individuals across months and identified sequences of movements between inside and outside of the labor force as well as between employment and unemployment. The coefficient estimates of model (a) should be interpreted as indicating the probability of changing labor market status relative to an individual whose status does not change the following period. My analysis characterizes labor market flows across three dimensions: (1) for women, (2), for jobs that can be performed remotely, (3) for women in jobs that can be performed remotely; thus, the omitted category is that of men in jobs that cannot be performed remotely. Furthermore, I augment model (a) by controlling for a number of other demographic characteristics that are important correlates of remote ability as well as a large set of fixed effects (month, state-year, industry-year, and occupation-year) that absorb the variation in labor market flows common across months, geographies, industries, and occupations.

Table 1 summarizes the results for labor force flows (panel A) and employment flows (panel B) of prime-age individuals. Starting with panel A, the first three columns look at labor force entry flows—that is, from out of the labor force to into the labor force. We find that (1) prime-age women are less likely to enter into the labor force, although the coefficient estimates are not significantly different from zero; (2) the ability to work remotely tend to boosts labor force entry for all prime-age individuals with a marginally insignificant effect in the specification with all controls; and (3) there is no significant differential effect on labor force entry for women, as the coefficient on the interaction $$ Female \ast Remote \ Ability $$ becomes insignificant in the full specification (column 3).

Table 1: Remote Work and Labor Market Flows, Prime-Age Individuals

Panel A: Flows in and out of the Labor Force

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry$$_{t}$$ | Exit$$_{t}$$ | |||||

| Female | -0.005 | -0.006 | -0.003 | 0.005*** | 0.005*** | 0.005*** |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Remote Ability | 0.019*** | 0.014*** | 0.009 | -0.003*** | -0.002*** | -0.001** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.006) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Female * Remote Ability | -0.013* | -0.011* | -0.006 | -0.002*** | -0.002*** | -0.002*** |

| (0.007) | (0.006) | (0.007) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Worker Observables | n | y | y | n | y | y |

| Month FE | n | n | y | n | n | y |

| State-Year FE | n | n | y | n | n | y |

| Industry-Year FE | n | n | y | n | n | y |

| Occupation-Year FE | n | n | y | n | n | y |

| Obs. | 16,077 | 16,077 | 16,077 | 1,694,078 | 1,694,078 | 1,694,078 |

| R-squared | 0.003 | 0.014 | 0.121 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.004 |

Panel B: Flows in and out of Employment

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry$$_{t}$$ | Exit$$_{t}$$ | |||||

| Female | -0.004 | -0.005 | -0.021*** | 0.008** | 0.008*** | 0.014*** |

| (0.011) | (0.009) | (0.007) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.002) | |

| Remote Ability | 0.083*** | 0.051*** | 0.027*** | -0.029*** | -0.018*** | -0.008*** |

| (0.011) | (0.009) | (0.008) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.002) | |

| Female * Remote Ability | -0.011 | -0.008 | 0.005 | -0.003 | -0.004 | -0.009*** |

| (0.013) | (0.011) | (0.009) | (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.002) | |

| Worker Observables | n | y | y | n | y | y |

| Month FE | n | n | y | n | n | y |

| State-Year FE | n | n | y | n | n | y |

| Industry-Year FE | n | n | y | n | n | y |

| Occupation-Year FE | n | n | y | n | n | y |

| Obs. | 77,998 | 77,998 | 77,998 | 1,621,802 | 1,621,802 | 1,621,802 |

| R-squared | 0.010 | 0.064 | 0.102 | 0.006 | 0.024 | 0.036 |

Notes: OLS regressions, 2003-2023. Columns (2)-(3) and (5)-(6) include worker observables (age, race, ethnicity, education, marital status, citizenship, tenure, and metro dummies); columns (3) and (6) also add month, state-year, industry-year, and occupation-year fixed effects. Robust standard errors, clustered at the occupation level, are reported in parenthesis.

Entry$$_{t}$$: indicator equal to 1 if the individual moves from out of the labor force into the labor force (panel A) or from unemployment to employment (panel B) between time $$t$$ and $$t-1$$.

Exit$$_{t}$$: indicator equal to 1 if the individual moves from in the labor force to out of the labor force (panel A) or from employment to unemployment (panel B) between time $$t$$ and $$t-1$$.

Female: dummy equal to 1 for women.

Remote Ability$$_{t}$$: indicator equal to 1 for occupations that require high use of e-mails, memos, and telephone.

Legend: *** denotes significance at 1 percent level, ** significance at 5 percent, and * significance at 10 percent.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration (USDOL/ETA)

Columns 4-6 analyze exit flows from the labor force—that is, from in to out of the labor force. We continue to find that (1) prime-age women are less attached to the labor force and more likely to exit, and that (2) the ability to work remotely significantly increases labor force attachment for all prime-age individuals. A novel finding is the additional differential benefit of remote ability for prime-age women: in fact, in contrast with the specifications in the first three columns, I find that prime-age women with access to remote jobs enjoy a lower probability of leaving the labor force. All told, women's ability to perform a job remotely almost entirely offsets their ex-ante lower labor force attachment.

Panel B expands the analysis by looking at flows in and out of employment. While the characterization of employment flows for (1) prime-age women and for (2) jobs that can be performed remotely is fairly similar to that of labor force movements on both entry and exit margins, the evidence on the differential effects of remote ability for prime-age women is less robust, with only a significant reduction in the probability of exiting employment in the full specification of column 6.

Table 2 explores whether the post-pandemic period brought changes in labor market flows across the same dimensions we highlighted above. Starting with panel A, except for an additional reduction in the probability of leaving the labor force for all prime-age individuals in the post-February 2020 period due to the ability to work remotely, we do not find other significant post-pandemic changes in labor force movements.

Table 2: Remote Work and Labor Market Flows, Comparison with Post-Pandemic Outcomes, Prime-Age Individuals

Panel A: Flows in and out of the Labor Force

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Exit | |||||

| Female | -0.008 | -0.008 | -0.006 | 0.005*** | 0.005*** | 0.005*** |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Female * Post Feb 2020 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.013) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Remote Ability | 0.017*** | 0.012*** | 0.010 | -0.003*** | -0.001*** | -0.001 |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.006) | (0.0005) | (0.0005) | (0.001) | |

| Remote Ability* Post Feb 2020 | 0.008 | 0.007 | -0.003 | -0.002*** | -0.002*** | -0.003*** |

| (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.013) | (0.0005) | (0.0005) | (0.001) | |

| Female * Remote Ability | -0.013* | -0.012* | -0.008 | -0.002*** | -0.002*** | -0.002*** |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.008) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Female * Remote Ability * Post Feb 2020 | -0.001 | 0.001 | 0.004 | -0.001 | -0.001 | -0.001 |

| (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Worker Observables | n | y | y | n | y | y |

| Month FE | n | n | y | n | n | y |

| State-Year FE | n | n | y | n | n | y |

| Industry-Year FE | n | n | y | n | n | y |

| Occupation-Year FE | n | n | y | n | n | y |

| Obs. | 16,077 | 16,077 | 16,077 | 1,694,078 | 1,694,078 | 1,694,078 |

| R-squared | 0.003 | 0.015 | 0.121 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.004 |

Panel B: Flows in and out of Employment

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Exit | |||||

| Female | -0.009 | -0.008 | -0.028*** | 0.006 | 0.006** | 0.014*** |

| (0.011) | (0.009) | (0.007) | (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.002) | |

| Female * Post Feb 2020 | 0.018 | 0.011 | 0.028** | 0.007** | 0.008** | 0.001 |

| (0.016) | (0.015) | (0.014) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| Remote Ability | 0.079*** | 0.043*** | 0.016* | -0.029*** | -0.017*** | -0.005* |

| (0.010) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| Remote Ability* Post Feb 2020 | 0.026* | 0.035*** | 0.042*** | -0.002 | -0.003 | -0.011*** |

| (0.014) | (0.013) | (0.016) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.004) | |

| Female * Remote Ability | -0.005 | -0.001 | 0.004 | 0.001 | -0.001 | -0.009*** |

| (0.012) | (0.010) | (0.009) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.003) | |

| Female * Remote Ability * Post Feb 2020 | -0.021 | -0.021 | -0.035* | -0.010*** | -0.009*** | -0.002 |

| (0.020) | (0.019) | (0.018) | (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| Worker Observables | n | y | y | n | y | y |

| Month FE | n | n | y | n | n | y |

| State-Year FE | n | n | y | n | n | y |

| Industry-Year FE | n | n | y | n | n | y |

| Occupation-Year FE | n | n | y | n | n | y |

| Obs. | 77,998 | 77,998 | 77,998 | 1,621,802 | 1,621,802 | 1,621,802 |

| R-squared | 0.013 | 0.066 | 0.109 | 0.006 | 0.024 | 0.039 |

Notes: OLS regressions, 2003-2023. All columns include the Post Feb. 2020 dummy. Columns (2)-(3) and (5)-(6) include worker observables (age, race, ethnicity, education, marital status, citizenship, tenure, and metro dummies); columns (3) and (6) also add month, state-year, industry-year, and occupation-year fixed effects. Robust standard errors, clustered at the occupation level, are reported in parenthesis.

Entry$$_{t}$$: indicator equal to 1 if the individual moves from out of the labor force into the labor force (panel A) or from unemployment to employment (panel B) between time t and t-1.

Exit$$_{t}$$: indicator equal to 1 if the individual moves from in the labor force to out of the labor force (panel A) or from employment to unemployment (panel B) between time t and t-1.

Female: dummy equal to 1 for women.

Post Feb. 2020: indicator equal to 1 for months after Feb. 2020.

Remote Ability$$_{t}$$: indicator equal to 1 for occupations that require high use of e-mails, memos, and telephone.

Legend: *** denotes significance at 1 percent level, ** significance at 5 percent, and * significance at 10 percent.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and USDOL/ETA.

Looking at employment flows in panel B, I document two main differences relative to the baseline analysis reported in table 1. First, prime-age men in jobs that can be performed remotely enjoyed an even higher likelihood of becoming employed in the post-pandemic period (columns 1-3). The same result does not apply to prime-age women as the coefficient on the interaction Female*Remote Ability* Post Feb 2020 is negative and mostly offsets the impact of Remote Ability*Post Feb 2020. Second, all prime-age individuals enjoy a lower probability of leaving the labor force in the post-pandemic period (columns 4-6), an effect that is significant only in the last column, but I do not find an additional differential impact of remote work for women in the post-pandemic period.

Taken together, these results suggest that changes to labor market flows for prime-age women brought by an increase in the share of jobs that can be performed remotely are not limited to the post-pandemic period but are likely reflective of broader labor market trends.

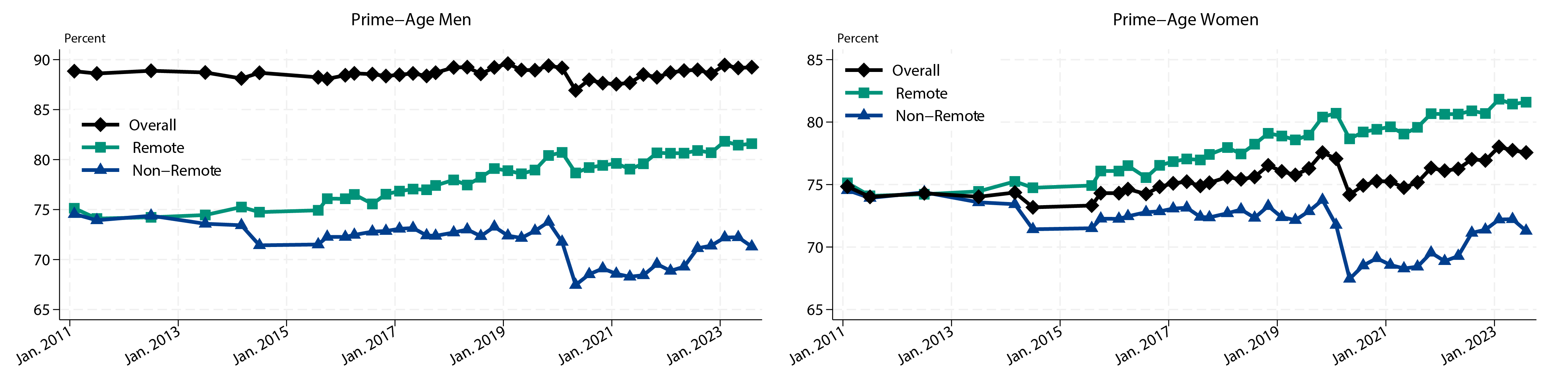

What are the direct implications for labor force participation? Figure 5 takes a reduced-form approach and compares labor force participation rates between the group of jobs that can be performed remotely (Remote, green line) and the group of jobs that cannot be performed remotely (Non-Remote, blue line) for both prime-age men (left panel) and women (right panel). Interestingly, since 2011, the overall improvement in labor force participation for all prime-age individuals is entirely linked to occupations that can be performed remotely; conversely, participation in non-remote occupations was flat or slightly declining. More recently, however, the relative importance of the two groups in explaining participation across prime-age men and women has changed. While the gap in participation for prime-age men between remote and non-remote jobs had mostly closed just before the COVID-19 pandemic and, subsequently, participation rates for the two groups of jobs have moved roughly in parallel, prime-age women in remote jobs continued to experience gains in participation from access to remote work throughout 2021; as the labor market continued to tighten into 2023, gains in participation accrued more rapidly to women in jobs that could not be performed remotely. This evidence is consistent with my findings from tables 1 and 2 suggesting that gains in labor force attachment reflect longer-term trends in the labor market rather than just post-pandemic developments.

Figure 5a (Left Figure)

Note: Labor force participation rate for prime−age men in jobs that can be performed remotely vs. jobs that cannot be performed remotely.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and USDOL/ETA.

Figure 5b (Right Figure)

Note: Labor force participation rate for prime−age women in jobs that can be performed remotely vs. jobs that cannot be performed remotely.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and USDOL/ETA.

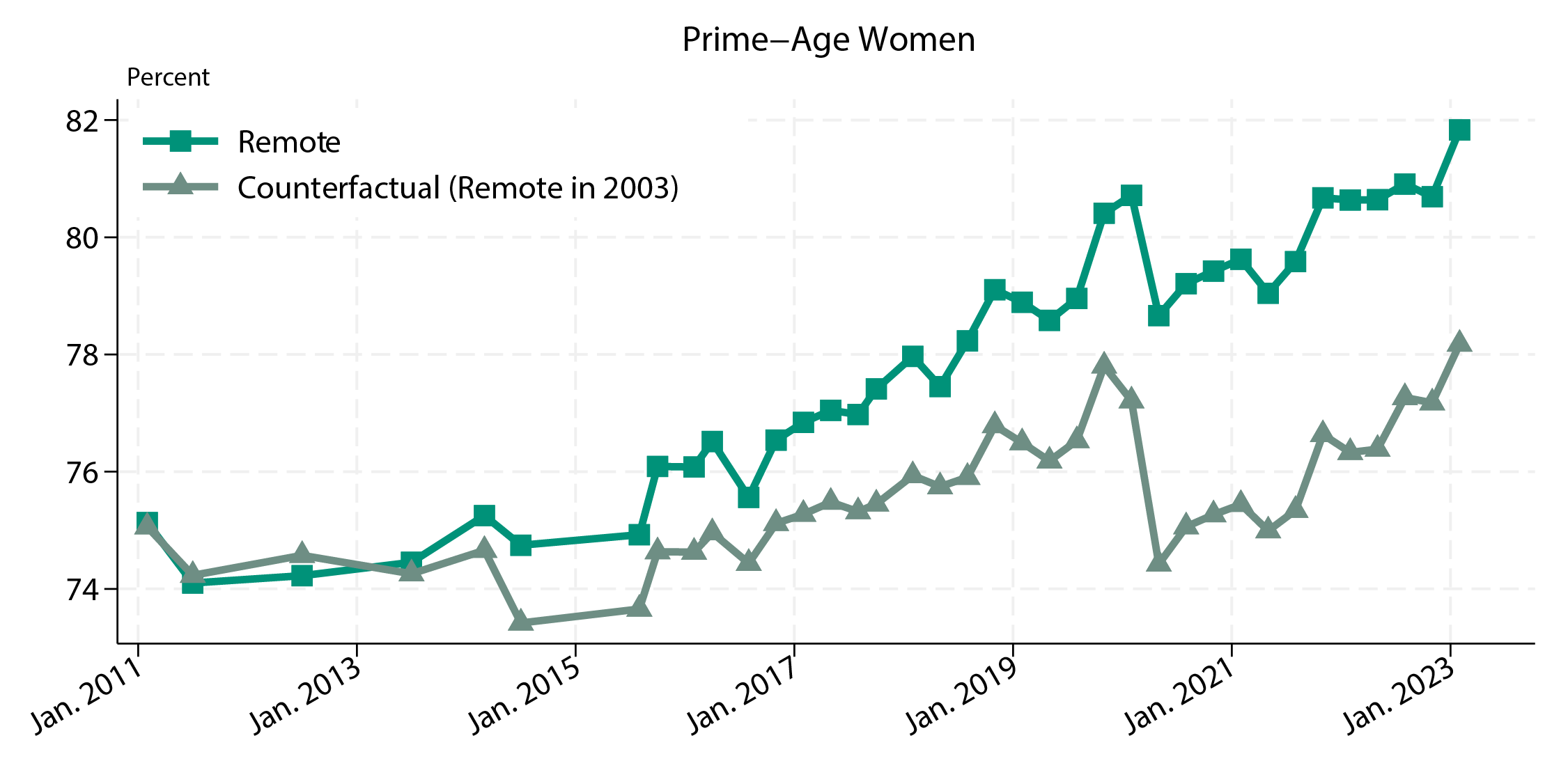

The improvement in remote participation summarized in figure 5 reflects two factors: (1) the selection of individuals into jobs that could traditionally be performed remotely and (2) the expansion in the number of occupations with remote ability over time. To disentangle between these two factors, I propose a counterfactual experiment. I construct a measure of labor force participation for prime-age women in jobs that could be performed remotely as of April 2003, the first month Langemeier and Tito (2022) develop the O*Net-based remote classification of jobs. The comparison with this counterfactual measure highlights what would have happened to prime-age female participation if there hadn't been any further advancement in remote ability after April 2003. Figure 6 compares the counterfactual measure of prime-age female participation (teal line) with the actual participation (green line) that takes on board the expansion in the set of jobs that can be performed remotely.

Figure 6. Counterfactual Experiment: Prime-Age Female Labor Force Participation, Current Remote Ability vs. Remote Ability as of April 2003

Note: Labor force participation rate for prime−age women in jobs that can be performed remotely vs. jobs that can be performed remotely as of April 2003.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and USDOL/ETA.

The counterfactual experiment confirms the importance of remote ability in shaping long-term trends. While participation in remote jobs improved since 2011, even for those that were already considered remote as of April 2003, the adoption of remote features in other occupations implied an even faster improvement for the prime-age women labor force participation rate. In the post-pandemic period, the improvement in the counterfactual measure (teal line) becomes more salient, particularly after 2022.

The last two exercises provide useful benchmarks to quantify the contribution of remote ability to the prime-age female labor force participation rate. In particular, the gap between participation in remote jobs and either non-remote participation or participation in occupations defined remote in the April 2003 classification identify differences that can be attributed to remote ability and its expansion over time. Table 3 summarizes the differences between prime-age female participation in remote jobs and the two benchmarks; it also calculates the additional contributions—Add.l Contribution in columns (2) and Add.l Counterfactual Contribution in column (4)—from each gap to the aggregate prime-age female labor force participation rate: in particular, if remote participation and the benchmarks were to move at similar rates, they would imply equal contributions to the aggregate measure; instead, since remote participation has been moving up more, the gap from the benchmarks identifies the additional contribution to the aggregate measure.7 The contribution to participation from remote ability, reported in column (2), has gradually increased over time, peaking in 2020, likely reflecting the effect of the pandemic. As shown in column 4, about 30 percent of the boost to participation from remote ability is due to the novel adoption of remote features in other occupations. More recently, instead, labor market improvements appear related to gains in participation in jobs that cannot be performed remotely, with the improvements in remote participation smaller than that of the overall prime-age female participation rate.

Table 3: Contribution of Remote Ability to Prime-Age Women Labor Force Participation

| Period | (1) Remote vs. Non-Remote (pp) | (2) Add.l Contribution (pp) | (3) Counterfactual (pp) | (4) Add.l Counterfactual Contribution (pp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012-2015 | 1.73 | 0.73 | 0.54 | 0.23 |

| 2016-2019 | 4.91 | 1.46 | 1.91 | 0.63 |

| 2020 | 10.29 | 2.72 | 4.01 | 1.06 |

| 2021 | 11.03 | 0.38 | 4.13 | 0.06 |

| 2022 | 10.55 | -0.25 | 3.93 | -0.10 |

| 2023 | 9.71 | -0.43 | 3.66 | -0.14 |

Note: Excess contribution of the ability to work remotely to changes in the prime-age women's LFPR. Column (2) reflects the impact of the Remote vs. Non-Remote gap from column (1), while columns (4) reports the effect of the Counterfactual gap from column (3).

Remote vs. Non-Remote: Difference between LFPR at jobs that can be performed remotely vs. jobs that cannot be performed remotely for prime-age women.

Counterfactual: Difference between LFPR at jobs that can be performed remotely vs. LFPR at jobs that could be performed remotely in April 2003.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and USDOL/ETA.

The COVID-19 pandemic shifted the attention to remote work, normalizing remote utilization. While the shift towards higher remote utilization is relatively recent, the ability to work remotely—which has significantly increased over the past few decades—has long influenced labor market outcomes and has created favorable conditions for particular demographic groups—such as, prime-age women.8 My analysis suggests that prime-age women have been capitalizing on the remote ability of their jobs and have been experiencing an increase in labor force attachment through a lower probability of exiting the labor force. Those gains, while particularly important at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, are the results of long-term trends rather than recent changes; in fact, in recent years, the improvement in prime-age women labor force participation mostly reflects gains in occupations that cannot be performed remotely, as the labor market continued to tighten. Even so, the influence of remote ability on a wide variety of labor market outcomes is here to stay, despite ongoing questions about the implications for productivity.9

References

Atkin, David, Antoinette Schoar, and Sumit Shinde (2023). "Working from Home, Worker Sorting and Development," NBER Working Paper Series 31515. Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, July (revised December), https://www.nber.org/papers/w31515.

Bauer, Lauren, and Sarah Yu Wang (2023). "Prime-Age Women Are Going Above and Beyond in the Labor Market Recovery," Brookings Institution, The Hamilton Project (blog), August 30, https://www.hamiltonproject.org/publication/post/prime-age-women-are- going-above-and-beyond-in-the-labor-market-recovery/.

Bartik, Alexander W., Zoe B. Cullen, Edward L. Glaeser, Michael Luca, and Christopher T. Stanton (2020). "What Jobs are Being Done at Home during the COVID-19 Crisis? Evidence from Firm-Level Surveys," NBER Working Paper Series 27422. Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, June, https://www.nber.org/papers/w27422.

Bloom, Nicholas, James Liang, John Roberts, and Zhichun Jenny Ying (2015). "Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment," Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 130 (February), pp. 165–218.

Brynjolfsson, Erik, John J. Horton, Adam Ozimek, Daniel Rock, Garima Sharma, and Hong-Yi TuYe (2020). "COVID-19 and Remote Work: An Early Look at US Data." NBER Working Paper Series 27344. Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, June, https://www.nber.org/papers/w27344.

Choudhury, Prithwiraj, Cirrus Foroughi, and Barbara Larson (2021). "Work‐from‐Anywhere: The Productivity Effects of Geographic Flexibility," Strategic Management Journal, vol. 42 (April), pp. 655–83.

Dingel, Jonathan I., and Brent Neiman (2020). "How Many Jobs Can Be Done at Home?" Journal of Public Economics, vol. 189 (September), 104235.

Gibbs, Michael, Friederike Mengel, and Christopher Siemroth (2023). "Work from Home and Productivity: Evidence from Personnel and Analytics Data on Information Technology Professionals," Journal of Political Economy Microeconomics, vol. 1 (1), pp. 7–41.

Hynes, Kathryn, and Marin Clarkberg (2005). "Women's Employment Patterns during Early Parenthood: A Group‐Based Trajectory Analysis," Journal of Marriage and Family, vol. 67 (February), pp. 222–39.

Langemeier, Kathryn, and Maria D. Tito (2022). "The Ability to Work Remotely: Measures and Implications." Review of Economic Analysis, vol. 14 (2), pp. 319–33.

Lu, Yao, Julia Shu-Huah Wang, and Wen-Jui Han (2017). "Women's Short-Term Employment Trajectories Following Birth: Patterns, Determinants, and Variations by Race/Ethnicity and Nativity," Demography, vol. 54 (1), pp. 93–118.

Montenovo, Laura, Xuan Jiang, Felipe Lozano Rojas, Ian M. Schmutte, Kosali I. Simon, Bruce A. Weinberg, and Coady Wing (2020). "Determinants of Disparities in COVID-19 Job Losses." NBER Working Paper Series 27132. Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, May (revised June 2021), https://www.nber.org/papers/w27132.

Morikawa, Masayuki (2020). "Productivity of Working from Home during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from an Employee Survey,", Covid Economics 49: 123–139.

U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps.html.

U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration (USDOL/ETA), O*Net 28.0 Database and Archives, used under the CC BY 4.0 license. O*NET® is a trademark of USDOL/ETA.

1. I would like to thank Chris Nekarda for generously sharing his data and Mariel Schwartz for her insightful comments. The views expressed in the article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve System. Return to text

2. In the CPS, whether a person worked remotely was determined through answers to the following question: "At any time in the last 4 weeks, did you telework or work at home for pay because of the coronavirus pandemic?" Among other survey measures, see Bartik et al. (2020) and Brynjolfsson et al. (2020). Return to text

3. People who reported to working remotely are those who indicated they teleworked or worked at home for pay at any time during the survey reference week. Return to text

4. Montenovo et al. (2020) characterize occupations as displaying the ability to work remotely if email, phone, and memo usage is very important; thus, their measure, appears to identify occupations featuring "remote communications". See Langemeier and Tito (2022) for a discussion of an alternative measure proposed by Dingel and Neiman (2020) as well as implications on aggregate labor market outcomes. Return to text

5. Occupation codes are missing for about one-third of my CPS sample; furthermore, I am not able to assign a "remote" classification for an additional 5 percent of the observations in the CPS. Other than for the May 2020 episode, the measure of remote utilization appears well-behaved over the rest of the sample period and across different demographic dimensions. Return to text

6. $$ y_{i,j \rightarrow k,st} $$ is equal to 1 if the individual moves from status $$j$$ to $$k$$. The comparison is for people that do not change status; thus, I set it equal to 0 if the individual remains in status $$j$$. My sample is restricted to individuals aged 25 to 54 years. Return to text

7. The contributions take into account the shares of remote, non-remote, and counterfactual components into the aggregate. Return to text

8. Following the disaggregation proposed by Bauer and Wang (2023) and their findings about the female labor force participation rates by the presence of young children, I repeat my analysis to take the presence of young children into account and confirm the importance of the ability to work remotely for that group. Return to text

9. Pre-pandemic studies, such as Bloom et al. (2015) and Choudhury et al. (2021) point to productivity gains associated with remote work, while, more recently, Morikawa (2020), Atkin et al. (2023), and Gibbs et al. (2023) find a negative impact on productivity. Return to text

Tito, Maria D. (2024). "Does the Ability to Work Remotely Alter Labor Force Attachment? An Analysis of Female Labor Force Participation ," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, January 19, 2024, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3433.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.