FEDS Notes

December 20, 2024

How Well-Anchored are Long-term Inflation Expectations in Latin America?1

Patrice Robitaille, Tony Zhang, and Brent Weisberg

I. Introduction

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru (hereafter referred to as the Latin 5) adopted inflation targeting frameworks as their monetary policy strategy, allowing greater exchange rate variability than in the past. By taking this step, policy makers aimed to put an end to a historical record of high and variable inflation. In this note, we focus on one facet of the Latin 5's performance under inflation targeting: central banks' efforts to build monetary policy credibility. We measure monetary policy credibility by examining to what extent long-term inflation expectations have become "well-anchored" to inflation targets, drawing on the evidence from surveys of professional forecasters and from financial markets.

Anchoring long-term inflation expectations can be particularly challenging in emerging market economies (EMEs), in part because EMEs experience frequent disturbances from abroad that can push inflation away from the target for some time. With confidence in the central bank's commitment to low inflation, inflation should eventually return to the inflation target.2 Ahmed, Akinci, and Queralto (2021) quantify the extent to which EMEs with greater monetary policy credibility are more resilient to U.S. monetary policy shocks. The post-pandemic surge in inflation around 2022-23 to its highest level since the 1990s in the Latin 5 offers an opportunity to explore whether the history of de-anchored long-term inflation expectations is now behind them.

In this note, we focus on readings on inflation at least five years in the future from surveys and financial markets, in line with several other studies, which tend to focus on advanced counties' experiences.3 Five years in the future is long enough such that the effects of any temporary disturbances on inflation have faded. Our main source of survey data is the Consensus Economics survey, which has surveyed professional forecasters for their views on inflation six to ten years in the future for the Latin 5 since the mid-1990s. These surveys were conducted bi-annually (in April and October) before April 2014 and have been conducted quarterly since then (January, April, July, and October). For Mexico, we also examine the evidence from the monthly survey of professional forecasters from the Bank of Mexico, which began to query views on inflation 5 to 8 years ahead in 2008. Our financial market-based evidence is based on the evolution of far forward inflation compensation, often also referred to as break-even inflation, for Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico. Data are not available for Peru. We examine inflation compensation 5 to 10 years ahead. Inflation compensation in the far future captures both investor views on where inflation will settle and a premium that investors demand for the possibility of upside inflation surprises. We update inflation compensation for Brazil and Mexico from De Pooter, Robitaille, Walker, and Zdinak (DPRWZ 2014), while for Chile and Colombia, we draw on data from central banks' websites.

In the survey data, we deem long-term inflation expectations to be well-anchored if the average long-term inflation forecast across forecasters has been close to the inflation target; if the average long-term inflation forecast has not been sensitive to revisions to past inflation or to revisions to the shorter-term inflation forecasts; and if forecasters tend to agree about the long-term inflation outlook. The degree of disagreement in inflation forecasts among forecasters is related to inflation uncertainty. From the financial market readings, we define long-term inflation expectations to be well-anchored if far forward inflation compensation is close to the inflation target. Overall, our look at the evidence indicates that long-term inflation expectations have become better- anchored to targets, particularly over the past decade. That said, inflation expectations are more weakly anchored in Brazil. And, the high premiums that investors demand to hold long-term nominal debt in Brazil and Colombia (and to some extent Mexico) highlights that building anti-inflation credibility remains an ongoing challenge.

II. Central Bank Reform and Inflation Targeting

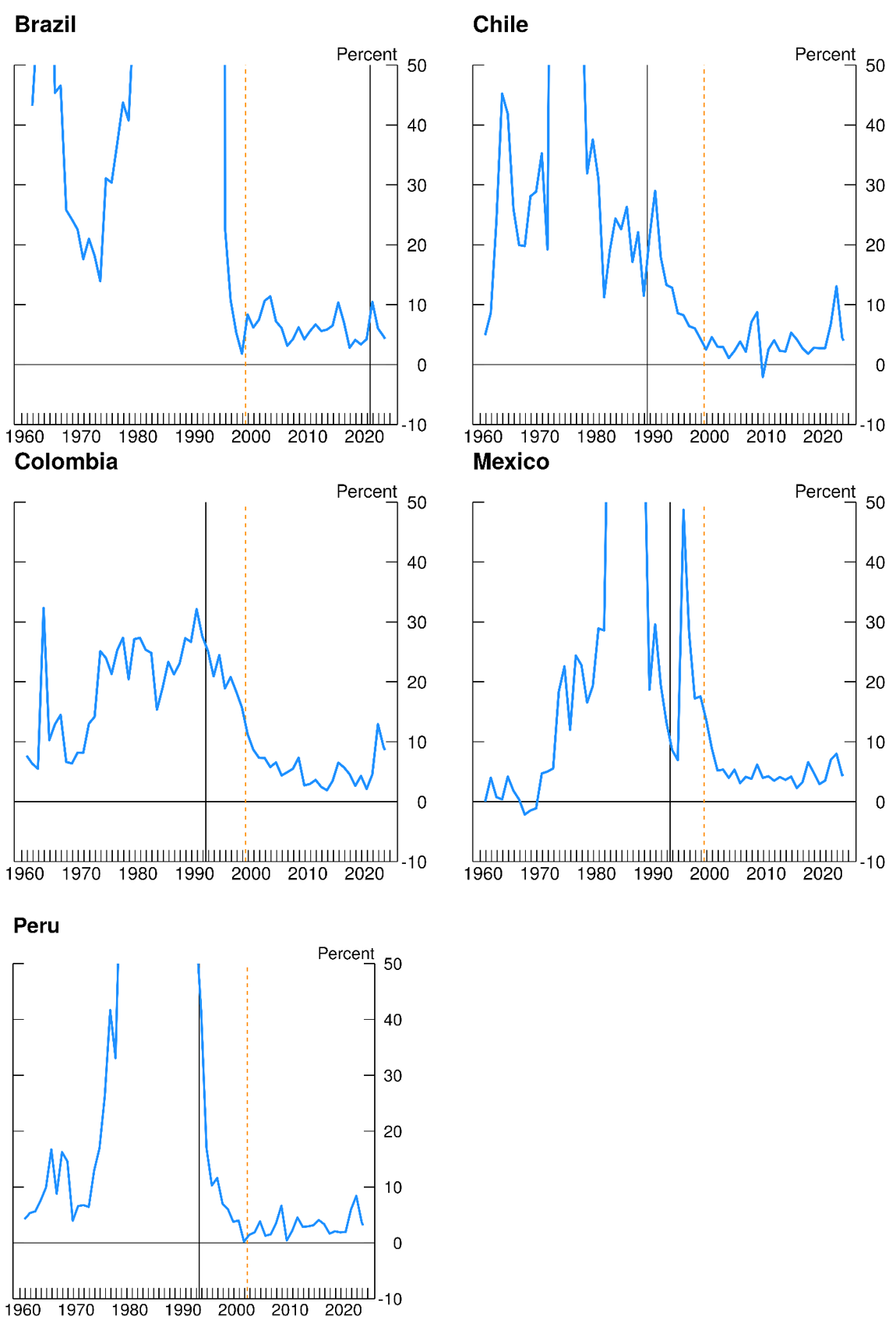

As can be seen by Figure 1, inflation in the Latin 5 was persistently high between the 1960s and 1990s, with Brazil and Peru suffering hyperinflations in the 1980s and early 1990s.4 In the figure, we omit inflation over 50 percent to make it easier to see when inflation fell to single digit levels in the 1990s. Persistently high inflation was ultimately the result of monetization of fiscal deficits, as monetary policy served fiscal goals.5 These historical experiences helped spur reforms in the late 1980s and early 1990s that granted greater independence to central banks in Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru (Table 1 and gray vertical lines in Figure 1). To free the central bank from fiscal demands, central bank reforms all either prohibited central banks from lending to the government or made it very difficult for central banks to do so (see Appendix 2).

Notes: Figure 1 displays the annual inflation rate, expressed as the Q4 over Q4 percent change in the CPI, computed from monthly data. Inflation rates above 50 percent are omitted for readability. Data for 2024 is 4-quarter inflation through the first quarter. For Mexico, inflation 1960-1969 is based on annual data. The vertical solid gray and dashed orange lines denote when the central bank became legally more independent and when the inflation targeting framework was announced.

Sources: Inflation data obtained from websites of the central Banks of Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru, and Haver Analytics. Details are in Appendix 1.

Table 1. Institutional Environment for Monetary policy

| Country | Year of Central Bank Independence | Inflation Targeting Framework Adopted |

|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 2021 | June 1999 |

| Chile | 1989 | Sept 1999 |

| Colombia | 1992 | Sept 1999 |

| Mexico | 1993 | Jan 2001 |

| Peru | 1993 | Jan 2002 |

Sources. International Monetary Fund's Central Bank Legislation Database, Haver Analytics.

Inflation targeting was adopted by the Latin 5, beginning with Brazil in June 1999, following the successful experiences of advanced countries, particularly New Zealand, the pioneer, but also motivated by dissatisfaction with alternative monetary policy strategies (see orange dashed vertical line in Figure 1 and Table 1). Although the Latin 5 reduced inflation in the 1990s, ending hyperinflation in Brazil, for Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico, disinflation was achieved under variants of fixed exchange rate regimes that were economically too costly to defend. Mexico and Peru experimented with money targets before adopting inflation targeting frameworks in 2001 and 2002 respectively—Mexico after having abandoned its fixed exchange rate policy during its currency crisis in 1994 (Mishkin and Savastano 2001). Although the Central Bank of Brazil was not granted greater political autonomy until 2021, under the inflation targeting framework, the central bank was empowered to direct its policy rate to the inflation goal, obtaining greater political independence.

As part of broader effort underway in the 1980s and 1990s to achieve greater macroeconomic stability, fiscal management also improved, and steps were taken to recapitalize banks and strengthen banking systems. Several fiscal and banking reforms are described in the country studies in Kehoe and Nicolini (2022). That said, fiscal challenges remain, particularly for Brazil and Colombia, where there have been concerns about the commitment to fiscal conservatism.6

III. Survey-Based Inflation Expectations for the Latin 5

For our purposes, the relevant inflation target is the long-term inflation goal. This presents complications because although the central banks of Chile, Mexico, and Peru stabilized their inflation target at 3 percent (2 percent for Peru) early, Colombia and Brazil underwent a longer disinflation.7 Mishkin and Schmidt-Hebbel (2007) classified Brazil and Colombia as undergoing disinflation. Colombia's central bank had set 3 percent as the long-term inflation target in late 2001. Nevertheless, balancing its desired inflation objective against other macroeconomic goals, the central bank continued to set higher medium-term inflation targets until 2009.8 3 percent is clearly the relevant inflation target for Colombia in our analysis. Brazil's government reviewed its target every year until a recent reform. Brazil's inflation target was initially gradually lowered in steps to promote gradual disinflation to about 3 percent, but then raised several times in the early 2000s (DPRWZ 2014). Between 2017 and 2021, Brazil's inflation target was gradually reduced from 4.5 percent to 3 percent. In June 2024, Brazil's government formalized that 3 percent is the stable inflation target, meaning that the inflation target will no longer be automatically reviewed every year. For Brazil, we use the longest-term official target at the time.

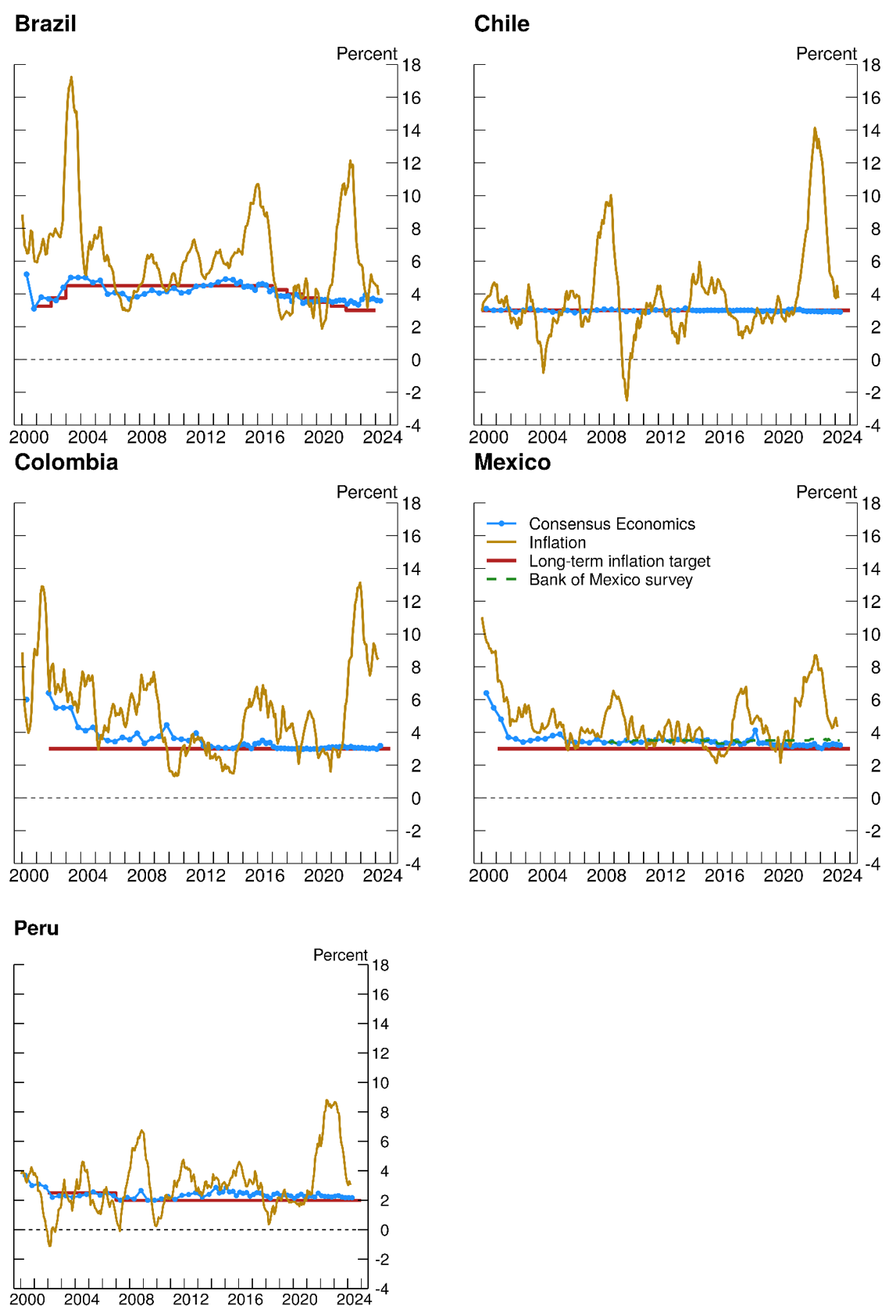

Figure 2 depicts 12-month headline inflation in each of the Latin 5 countries since 2000 (gold line), as well as the cross-sectional average forecast of long-term inflation (5- to 10- years ahead) from the Consensus survey (in blue ball and chain) and the inflation target (red line). For Mexico, Figure 2 also depicts the evolution of the median forecast for inflation 5 to 8 years ahead from the Bank of Mexico's monthly survey of professional forecasters (green dashed line).9 The inflation forecasts are compared to the inflation target.

Notes: In each chart, the gold line displays 4-quarter headline inflation between Q1 2000 and Q1 2024. Headline inflation is compared to the inflation target and to the cross-sectional average in professional forecasters' 6 to 10 year ahead inflation forecast from Consensus Economics (blue ball and chain). For Mexico, the green dashed line displays the cross-sectional average forecast for inflation 5 to 8 years ahead from the Bank of Mexico's monthly survey of professional forecasters. The inflation target for Colombia is the 3 percent "long-term" inflation goal announced by the central bank in late 2001, as is detailed in the text. For Brazil, the inflation target shown is the longest-term inflation target in effect at the time.

Sources: Consensus Economics, Central Bank of Brazil, Bank of Mexico, and Haver Analytics.

Levin, Natalucci, and Piger (LNP 2004) document the sharp fall in the average long-term inflation forecasts in the 1990s, which is not shown here. Figure 2 indicates that despite wide variations in inflation, the cross-sectional average long-term inflation forecast has moved relatively little for the Latin 5, even amid the post-pandemic inflationary surge. Long-run inflation expectations have been remarkably well-anchored to the 3 percent target in Chile. Long-term inflation forecasts have been well-anchored in Colombia to the central bank's 3 percent target since the December 2012 survey, suggesting that it took several years for professional forecasters to become more convinced that the central bank would pursue the 3 percent goal. For Mexico, the average forecast has been usually 1/4 to 1/2 percentage point above the 3 percent target in the Consensus Economics and Bank of surveys. For Brazil, the average long-term inflation forecast was more variable, drifting a little above the target in the mid-2010s and peaking at 4.9 percent in the December 2013 survey. More recently, after the inflation target declined to 3 percent, the average forecast was nearly 4 percent in the second quarter of 2023 but subsequently declined to about 1/2 percentage point above the target. The long-term forecast for Peru moved up to nearly 3 percent in 2014 and 2015, but has since then settled close to the 2 percent target. For perspective, over the 2004 to 2019 period, 4-quarter inflation averaged 5.6 percent in Brazil, 3.2 percent in Chile, 4.3 percent in Colombia, 4.1 percent in Mexico, and 2.9 percent in Peru.

More formally, following LNP (2004), we test whether the cross-sectional average long-term inflation expectations has been sensitive to past inflation by estimating the following equation:

ΔEtπt+j=α+β1Δ¯πt+β2×Dpost2013×Δ¯πt+ϵt,

where ΔEtπt+j denotes the change in the cross-sectional average forecast of long-term inflation (from the Consensus Forecast survey), Δ¯πt denotes the change in the trailing 3-year moving average of 12-month inflation, and ϵt is the disturbance term. The sample period is April 2000 to April 2024, bi-annual through 2013, and quarterly thereafter. We add an interactive dummy, Dpost2014×Δ¯πt to test whether the average long-term inflation forecast has become more or less sensitive to past inflation since 2014, the last 10 years of the sample.

As reported Table 2, the coefficients on past inflation are not statistically significant from zero in Brazil, Chile, and Peru. For Colombia and Mexico, although the coefficients are positive and statistically significant, the sensitivity of long-term inflation forecasts to past inflation can be traced to the pre-2014 period. A one percentage point rise in past inflation raises the long-term forecast by 0.89 percentage points for Colombia and 0.29 percentage points for Mexico, but that sensitivity disappears over the latter part of the sample, with the coefficient for both countries close to zero (=0.89-0.94= -0.05 percentage points for Colombia and 0.29-0.34= -0.05 percentage point for Mexico).

Table 2. Sensitivity of Long-term Inflation Forecasts to Past Inflation

| Brazil | Chile | Colombia | Mexico | Peru | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | -0.01 |

| (0.05) | (0.01) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Change Past Inflation | 0.06 | -0.01 | 0.89* | 0.29** | 0.11 |

| (0.08) | (0.03) | (0.23) | (0.12) | (0.11) | |

| Change Past Inflation X post-2014 | -0.03 | 0.00 | -0.94* | -0.34** | -0.09 |

| (0.13) | (0.03) | (0.25) | (0.14) | (0.13) | |

| Adjusted R squared | -0.03 | -0.03 | 0.47 | 0.33 | -0.01 |

| Observations | 69 | 69 | 66 | 69 | 69 |

* p value < 0.01, ** p value < 0.05, *** p value < 0.10

Notes: Sample period is April 2000 to April 2024. Reflecting the availability of survey data from Consensus Economics, the sample is bi-annual before 2014 and quarterly thereafter. For Colombia, there are 3 missing observations at the beginning of the sample, in October 2000, April 2001, and October 2001. The dependent variable is the cross-sectional average of 6- to 10- year ahead inflation forecasts from the Consensus Economics survey. The table reports the results of regressing the change in the average long-term inflation forecast on a constant, the change in past inflation, and an interactive dummy. Past inflation is the change in the 3-year trailing moving average of past 12-month CPI inflation. The interactive dummy is set to 1 for observations beginning January 2014. HAC-adjusted standard errors are shown in parentheses.

Taking an alternative approach, we follow Castelnuovo, Nicoletti-Altimari, Sergio and Rodriquez-Palenzuela (2003) by examining whether revisions to the average long-term inflation forecast comove with changes in the average one-year-ahead ("shorter-term") inflation forecast, estimating the following equation:

ΔEtπt+j=α+β1ΔEtπt+1+β2×Dpost2013×ΔEtπt+1+ϵt,

where ΔEtπt+1 is the change in the average one-year ahead inflation forecast and Dpost2014×ΔEtπt+1 is the interactive dummy term. Because the Consensus Forecast survey's shorter-term inflation forecasts are for calendar years, we construct pseudo one-year-ahead inflation forecasts by taking a weighted average of the current and following year forecast, with the relative weights determined by the number of months that remain in the current year. The results, displayed in Table 3, indicate that long-term forecasts have in recent years comoved with shorter-term forecasts only in Brazil. A one percentage point rise in one-year-ahead inflation forecast is associated with a 0.14 percentage point rise in the long-term inflation forecast. For Colombia, Mexico, and Peru, the sensitivity of long-term inflation expectations to changes in shorter-term inflation forecasts can again be traced to the pre-2014 period. Overall, the regression results suggest that long-term inflation expectations have been well anchored to the inflation targets over the past decade but have been more weakly anchored in Brazil.

Table 3. Relationship Between Long-term and Short-term Inflation Forecasts

| Brazil | Chile | Colombia | Mexico | Peru | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.01 | 0.00 | -0.05 | -0.02 | -0.01 |

| (0.05) | (0.01) | (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

| Change 1-Year Ahead Inflation Forecast | 0.14** | 0.03 | 0.51* | 0.39* | 0.24* |

| (0.06) | (0.01) | (0.19) | (0.05) | (0.06) | |

| Change 1-Year Inflation Forecast X post-2014 | 0.00 | -0.03 | -0.47** | -0.36* | -0.22** |

| (0.13) | (0.02) | (0.23) | (0.09) | (0.11) | |

| Adjusted R squared | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.43 | 0.17 |

| Observations | 69 | 69 | 66 | 69 | 69 |

* p value < 0.01, ** p value < 0.05, *** p value < 0.10

Notes: Sample period is April 2000 to April 2024. For Colombia, there are 3 missing observations near the beginning of the sample, in October 2000, April 2001, and October 2001. Data are bi-annual through 2013 and quarterly thereafter. The dependent variable is the cross-sectional average of 6- to 10- year ahead inflation forecasts from the Consensus Economics survey. Table 3 reports the results of regressing the change in the average long-term inflation forecast on a constant, the change in the one-year-ahead inflation forecast, and the interactive dummy. Because the Consensus Forecast survey's shorter-term inflation forecasts are for calendar years, we construct one-year ahead forecast by taking a weighted average of the current and following year forecast, with the relative weights determined by the number of months that remain in the current year. The interactive dummy is set to 1 for observations beginning January 2014. The standard errors are shown in parentheses.

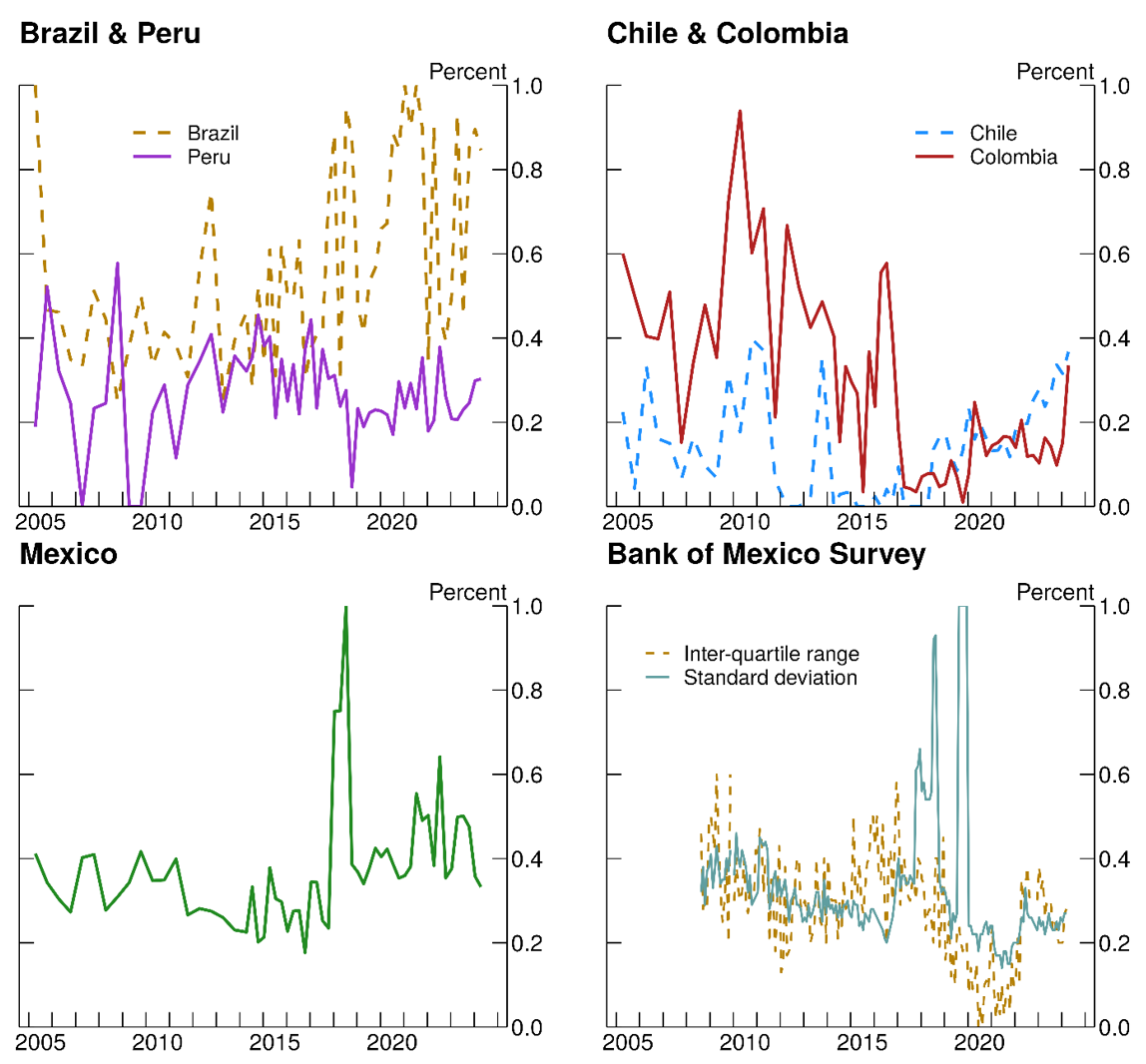

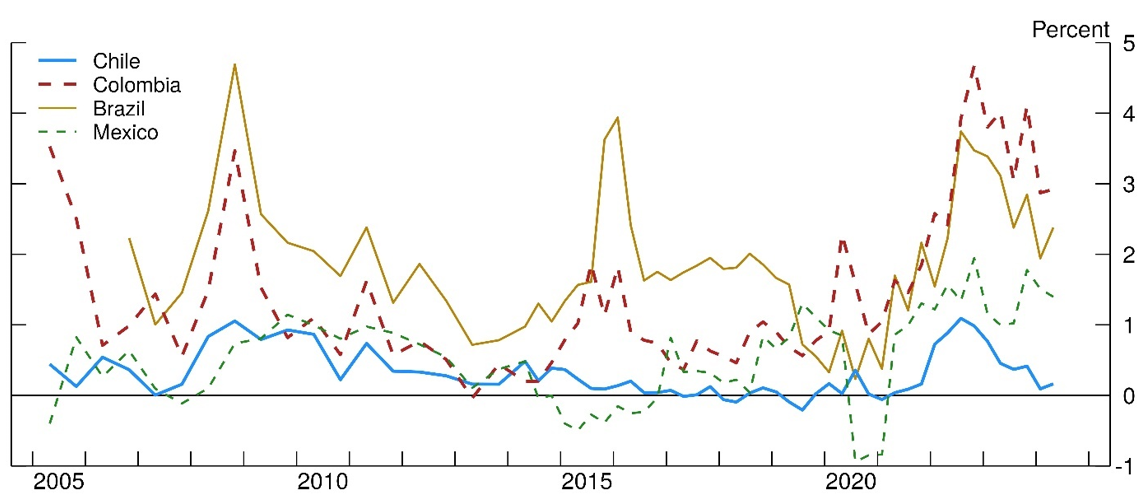

For inflation expectations to be well-anchored, there also should be a high degree of consensus among forecasters that inflation will eventually settle to the target (Beechly, Johannsen, and Levin 2011). The first three panels in Figure 3 plot the standard deviation of long-term inflation forecasts across forecasters from the Consensus Survey, beginning in 2005, when the data first become available. The last panel displays the standard deviation and interquartile range in forecasts for inflation 5 to 8 years in the future from the Bank of Mexico's monthly survey. The graphs for Mexico are truncated at 1.0 to facilitate comparisons between Mexico and other countries outside of certain periods (discussed below) when the decree of disagreement among forecasters spiked.

Notes: Shown in the first three charts is the cross-sectional standard deviation of long-term inflation forecasts from Consensus Forecasts. The data first become available in 2005. For Mexico, displayed in the fourth panel are two measures of dispersion in long-run inflation forecasts (5 to 8 years ahead) from the Bank of Mexico's monthly survey of professional forecasters, the cross-sectional standard deviation in long-term forecasts (teal line) and the interquartile range (dashed orange line). These data first become available in 2008.

Sources: Consensus Economics, Bank of Mexico.

For Brazil, and, for Colombia before 2014, professional forecasters disagreed about the long-term inflation outlook to a greater degree than in other countries. In the April 2024 survey, the standard deviation of the long-term inflation forecasts for Brazil was over 0.8 percent, more than double that of the other countries, further evidence that long-term inflation expectations for Brazil are more weakly anchored than for the other countries. For Colombia, the degree of cross-sectional dispersion in forecasts fell after 2016, suggesting that forecasters tended to agree to a greater extent that the central bank would pursue the 3 percent goal for inflation. Measures of dispersion in long-term inflation forecasts for Mexico spiked in 2017-18 and in 2019, possibly reflecting concerns that the commitment to fiscal and monetary discipline might wane under the incoming left-wing government, which was elected July 2018 and took office the following December.10 The standard deviation of long-term inflation forecasts in the Bank of Mexico surged to over 2.7 percent between August and December 2019, but owing to one outlier—an extremely high forecast of 20 percent (Bank of Mexico 2019). Amid the rise in inflation in recent years, the degree of dispersion in long-term forecasts has moved up for both Chile and Colombia.

IV. Evidence from Financial Markets

Evidence from financial market readings of long-term inflation, far-forward inflation compensation, from Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico, countries for which we have the required high frequency financial data, provides insights into the degree to which the distribution of long-term inflation expectations have been well-anchored. Chile's government first issued long-term nominal bonds in the late 1990s, while Colombia's, Mexico's, and Peru's governments first did so in the early 2000s and Brazil in mid-2006. The fact that all 5 countries have been able to issue long-term nominal bonds is a sign of improved anti-inflation credibility, as previously, governments did not issue these bonds because the premiums that investors demanded as compensation for inflation risk were exorbitantly high.

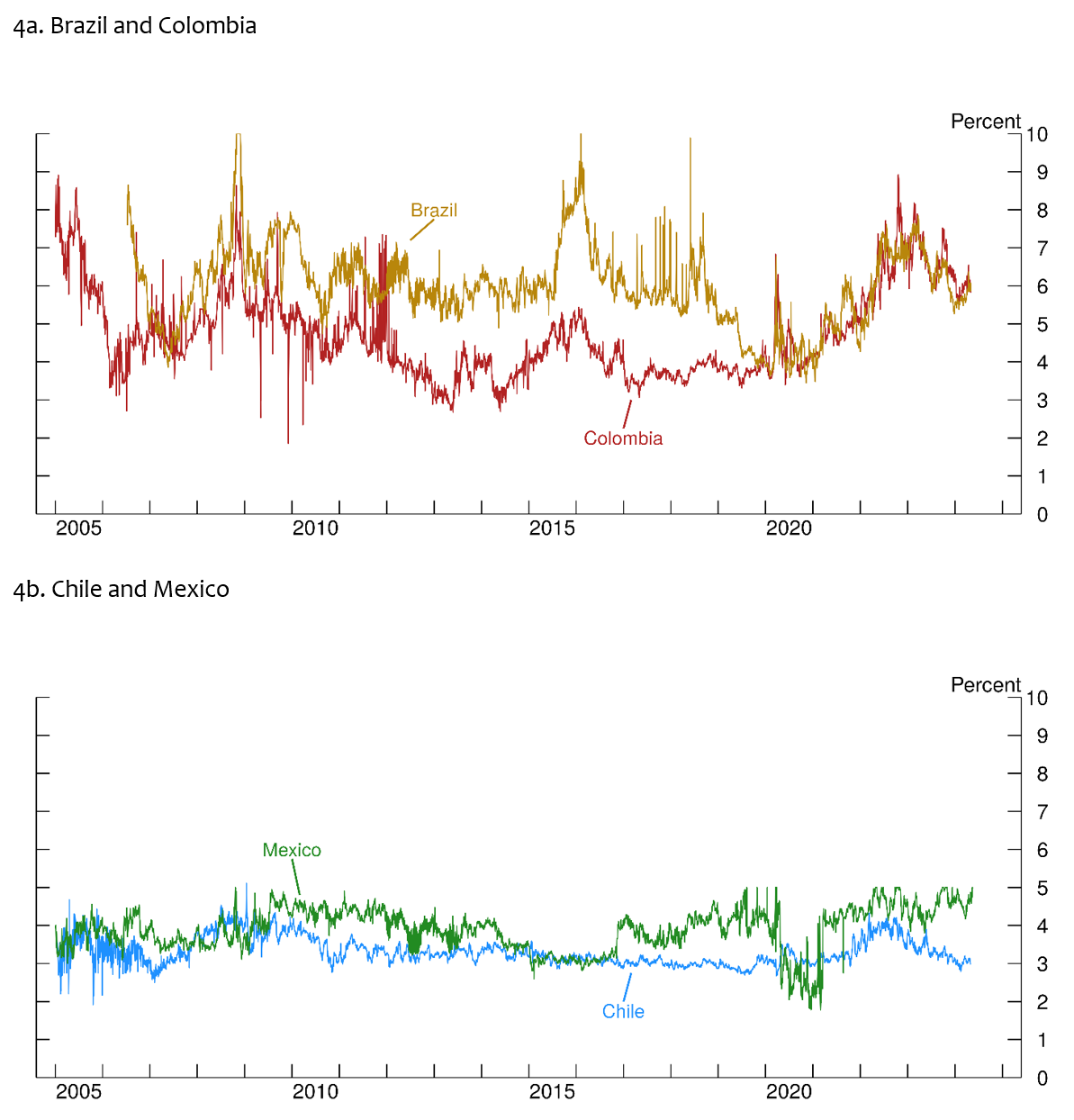

We focus on the 5-year forward rate for inflation compensation ending in 10 years. Inflation compensation is the difference between the yield on nominal bonds and inflation-linked bonds for Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico, whereas for Chile, we use far forward inflation compensation derived from inflation swaps. The evolution of far-forward inflation compensation is displayed in Figure 4 from January 1, 2005 (Brazil beginning in 2006) to April 30, 2024.

Notes: Shown is the 5-year forward rate for inflation compensation ending in 10 years, beginning whenever there were sufficient data to construct zero coupon yield curves to April 30, 2024.

Sources: Constructed by the authors, except for Chile, where inflation compensation is from the Central Bank of Chile's website. For Colombia, the Banco de la República posts daily data on zero coupon yields on nominal and inflation indexed data. We used these data, which we accessed via Haver Analytics, to construct far forward inflation compensation. For Brazil and Mexico, far forward inflation compensation was obtained from the data used by DePooter, Robitaille, Walker, and Zninek (2014) through 2011. Forward yields after that were constructed by the authors using bond yields data from Bloomberg for the period January 1, 2012 to April 30, 2024.

Far forward inflation compensation can be volatile, possibly reflecting liquidity issues or zero-coupon estimation errors, particularly during the Global Financial Crisis and in 2020, at the height of market stresses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Generally, as in DPRWZ, inflation compensation has been well above the inflation target in Brazil (gold line, Figure 4a). Even though Brazil's inflation target was gradually reduced to 3 percent between 2017 and 2021, far forward inflation compensation had ratcheted up since 2020 amid the rise in inflation, peaking at about 8 percent in 2022 before falling to about 6 percent. For Colombia, far forward inflation compensation (red line, Figure 4a) in recent years has also risen, but is down from its peak. Far forward inflation compensation on Mexican government bonds has been somewhat more stable and lower, but still was approaching 5 percent towards the end of our sample period (see also Beauregard, Christensen, and Fischer 2024). By contrast, far forward inflation compensation in Chile, also rising during the post-pandemic inflation surge, has been declining and recently has been close to the 3 percent inflation target.

For Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico, investors appear to have been demanding a premium for risk that inflation will be higher than the inflation target. A rough way of assessing the magnitude of the inflation risk premium is to subtract the average survey-based forecast of long-term inflation from inflation compensation. We first average inflation compensation over the same quarter as the survey, and then subtract the survey-based average (from Consensus Economics for all for countries). The evolution of this estimate of the inflation risk premium is shown in Figure 5. The inflation risk premium rose in all four countries in 2022, when inflation reached its highest level since the late 1990s (since 2003 for Brazil). The inflation risk premium subsequently declined to about zero for Chile. The inflation risk premium has declined elsewhere, but to 2 to 3 percent for Brazil and Colombia, and to about 1 percent in Mexico. Overall, the market perception of the distribution of long-run inflation outcomes has been fairly well anchored in Chile, but less so elsewhere.

Notes: Shown is the evolution of our estimate of the inflation risk premium, which we construct by subtracting from far forward inflation compensation (5-year inflation compensation ending in 10 years) the average long-term inflation forecast (6 to 10 years ahead) from the Consensus Forecast. Far forward inflation compensation was averaged over the same quarter as the Consensus Forecast survey as is described in the text. Observations prior to 2014 are bi-annual and quarterly thereafter.

Sources: As described in Figures 2 and 4.

V. Concluding Remarks

In this note, we explore whether long-term inflation expectations have become better-anchored in 5 Latin American countries that have a historical record of high inflation using both survey-based evidence and (for all countries but Peru) evidence from financial markets. Overall, Latin 5's historical record of very high inflation is seen as a relic of the past. Long-term inflation forecasts have been close to the inflation targets in recent years in all 5 countries, despite the post-pandemic surge in inflation. That said, long-term inflation expectations appear to be more weakly anchored in Brazil than in other countries, and the degree of dispersion in long-term inflation forecasts across professional forecasters has been relatively high for Brazil. Far forward inflation compensation has been relatively high in Brazil and Colombia, suggesting that investors place greater odds on the risk that inflation will settle to a higher-than-target level, whereas there the inflation risk premium for Chile has been generally much lower and recently about zero.

These differences among the Latin 5, at least for the past decade, do not appear to reflect differing priorities for inflation objectives versus other macroeconomic objectives. The recent findings of Guerra, Kamin, Kearns, Upper, and Vakil (2024, Table 8) indicate that these central banks were very responsive to deviations in inflation from target, particularly the Central Bank of Brazil. Further work could explore differences in central bank behavior and examine other potential explanations for our results. Candidate explanations include concerns that the inflation target might be eventually raised to pursue other macroeconomic objectives and concerns that monetary policy might eventually accommodate fiscal pressures.

Appendix 1: Sources of Inflation Data

Brazil. Data were obtained from the Central Bank of Brazil (https://www.bcb.gov.br/). Prior to 1980, inflation is the consumer price index from Sao Paulo (IPC-Fipe, Series 193). From 1980 on, national CPI is the Broad Nacional CPI (series 433).

Chile. From 1960 to February 1974, the national consumer price index is from the Central Bank of Chile (https://www.bcentral.cl). Thereafter, the national CPI is obtained from Haver Analytics (series N228PC@EMERGELA).

Colombia. 1960-2018 is derived from national consumer price index that was downloaded from Banco Central de la Republica de Colombia (https://banrep.co), Table 1.2.2, Series Índice de precios al consumidor (IPC)_Base diciembre 2008. From 2018 on, the national CPI is obtained from Haver Analytics (series N233PC@EMERGELA).

Mexico. Inflation 1960 to 1969 is based on the annual CPI for Mexico City, from INEGI (2014), Table 18.21. The national CPI begins in 1969 and is obtained from Haver Analytics (series N273PC@EMERGELA), which was used to compute headline inflation 1970.

Peru. 1960-1990 is based on the monthly CPI for metropolitan area of Lima, from Banco de la Reserva (https://estadisticas.bcrp.gob.pe/estadisticas/mensuales/inflacion, Series PN0127PM). From 1991 on, national CPI is obtained from Haver Analytics (series N293PC@EMERGELA).

Appendix 2: Central Bank Reforms and Restrictions on Lending to the Government

A central objective of the constitutional reforms in Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru in the late 1980s and early 1990s was to limit fiscal pressures on the central bank. The central bank reforms differed in terms of the institutional environment, but the reforms all either prohibited central banks from lending to the government or made it very difficult for the central bank to do so. Legislative details below were obtained from the IMF's database on central bank legislation (known as the CBLD) and for Brazil, also from the Central Bank of Brazil's website.

Chile. Under Chile's 1989 constitution, the central bank cannot lend to the government (Title III, Subtitle One, Section 27, and Klug, Calvo, Geraats, Kohn, and Mendoza 2019).

Colombia. Under the 1991 constitution, Colombia's central bank can make a loan to the government only with the unanimous approval of the executive board (Article 373). Colombia's central bank has yet to make a loan to the central government (Perez-Reyna and Osorio-Rodriguez 2021 and Banco de la Republica de Colombia 2021).

Mexico. Under Mexico's 1993 constitutional reform, no one can compel the Bank of Mexico to lend (article 28). The Bank of Mexico's organic law specifies that the central bank can buy government securities subject to certain provisions (Bank of Mexico 1993 Organic Law, Article 9). The objective is to support the Bank of Mexico's monetary management, rather than being for the purpose of extending credit to the government (Bank for International Settlements, undated). There are also limits on overdrafts by the government on its account with the Bank of Mexico (Bank of Mexico 1993 Organic Law, Articles 11 and 12).

Peru. The Bank is prohibited from conceding financing to the state treasury, except for the purchase, in the secondary market, of securities emitted by the Public Treasury, within the limits specified in its Organic Law (Article 83 of the Constitution of Peru of 1993).

Brazil's 1988 constitution banned the central bank from directly or indirectly lending to the national treasury (Article 164, paragraph 1 of the 1988 Constitution of Brazil). Nevertheless, the Brazil continued to suffer very high inflation under the late 1990s. The 2021 central bank autonomy law (Complementary Law No. 179) better- insulates the central bank from fiscal demands in part by making explicit that the central bank's primary objective is to ensure price stability (Article 1). In addition, the Central Bank of Brazil "is a special nature agency characterized by the absence of ties or hierarchical subordination to any Ministry by its technical, operational, administrative, and financial autonomy." (Complementary Law No. 179, Article 6). The law was challenged, but the following August, the Brazilian supreme court declared the law to be constitutional in an 8 to 2 vote (Reuters 2021).

As is the case for the central banks of Chile, Colombia, and Mexico, Brazil's central bank board members serve fixed and staggered terms in office. Chile's central bank board members serve by far the longest term, 10 years. Although the 5-year tenure of the board of Peru's central bank is tied to that of the executive, the central bank president has been in office since 2006, despite several changes in government.

Selected References

Ahmed, Shaghil, Ozge Akinci, and Albert Queralto. "US monetary policy spillovers to emerging markets: both shocks and vulnerabilities matter." FRB of New York Staff Report, no. 972 (2021).

Banco de la República de Colombia, "Metas de Inflación para 2002 y 2003." November 22, 2001.

Bank of Mexico, Survey of Expectations of Specialists in Economics in the Private Sector (in Spanish), August 2019, https://www.banxico.org.mx/publicaciones-y-prensa/encuestas-sobre-las-expectativas-de-los-especialis/encuestas-expectativas-del-se.html.

Beauregard, Remy, Jens H.E. Christensen, Eric Fischer, and Simon Zhu. "Inflation Expectations and Risk Premia in Emerging Bond Markets: Evidence from Mexico." Journal of International Economics 151, no. 103961 (2024).

Beechey, Meredith J., Benjamin K. Johannsen, and Andrew T. Levin. "Are Long-Run Inflation Expectations Anchored More Firmly in the Euro Area than in the United States?" American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 3, no. 2 (2011): 104–29.

Brock, Philip L. "Reserve Requirements and the Inflation Tax." Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 21, no. 1 (1989): 106–21.

Capurro, Maria Eloisa, "Brazil's Widening Fiscal Deficit Pressures Budget Goals." Bloomberg, January 5, 2024.

Castelnuovo, Efrem, Sergio Nicoletti Altimari, and Diego Rodriguez-Palenzuela. "Definition of price stability, range and point inflation targets: The anchoring of long-term inflation expectations." European Central Bank Working Papers, no. 273 (2003).

Consensus Economics, Inc. Consensus Forecasts Subscription, http://www.consensuseconomics.com/.

The Economist, "Under Lula, Brazil is walking on the financial wild side." July 18, 2024.

FitchRatings, "Colombia's Fiscal Consolidation Plans Still Face Significant Challenges," July 3, 2024.

Garcia, Juan Angel, and Sebastian Werner. Inflation news and Euro area inflation expectations. International Journal of Central Banking, September 2021.

Gómez-Pineda, Javier G., Jose Dario Uribe, and Hernando Vargas. "The implementation of inflation targeting in Colombia." Borradores de Economía, no. 202 (2002).

Guerra, Rafael, Steven Kamin, John Kearns, Christian Upper, and Aatman Vakil. "Latin America's non-linear response to pandemic inflation." BIS Working Papers, no. 1209 (2024).

Gürkaynak, Refet S., Andrew T. Levin, Andrew N. Marder, and Eric T. Swanson. "Inflation Targeting and the Anchoring of Inflation Expectations in the Western Hemisphere." Economía Chilena 9, no. 3 (2006): 19–52.

Gürkaynak, Refet S., Andrew Levin, and Eric Swanson. "Does inflation targeting anchor long-run inflation expectations? Evidence from the US, UK, and Sweden." Journal of the European Economic Association 8, no. 6 (2010): 1208-1242.

Hamann, Franz, Marc Hofstetter, and Miguel Urrutia. "Inflation targeting in Colombia, 2002–12." Economía 15, no. 1 (2014): 1-37.

International Monetary Fund, Article IV Consultation for Colombia, March 2024a.

___, Article IV Consultation for Brazil, July 2024b.

Levin, Andrew T., Fabio M. Natalucci, and Jeremy M. Piger. "The macroeconomic effects of inflation targeting." Review (Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis) 86, no. 4 (2004): 51-80.

Kehoe, Timothy and Pablo Nicolini, eds. A Monetary and Fiscal History of Latin America, 1960-2017. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2022.

Mishkin, Frederic S., and Miguel A. Savastano. "Monetary policy strategies for Latin America." Journal of Development Economics 66, no. 2 (2001): 415-444.

Miskin, Frederic S., and Klaus Schmitt-Hebbel. 2007. "Does Inflation Targeting Make a Difference?" In Monetary Policy under Inflation Targeting. Central Banking, Analysis, and Economic Policies Book Series. 291–372. Santiago, Chile: Central Bank of Chile.

Morandé, Felipe. "A Decade of Inflation Targeting in Chile: Developments, Lessons, and Challenges." Central Banking, Analysis, and Economic Policies Book Series 5 (2002): 583-626.

De Pooter, Michiel, Patrice T. Robitaille, Ian Walker, and Michael Zdinak. "Are long-term inflation expectations well anchored in Brazil, Chile and Mexico?" International Journal of Central Banking 10, no. 2 (2014): 337-400.

Reuters, "Brazil's top court upholds central bank autonomy amid rising inflation," August 26, 2021.

Svensson, Lars EO. "Inflation targeting." In Handbook of Monetary Economics, vol. 3, pp. 1237-1302. Elsevier, 2010.

1. Patrice Robitaille (Patrice.robitaille@frb.gov), Tony Zhang (Tony.Zhang@frb.gov), and Brent Weisberg (Brent.g.Weisberg@frb.gov) are with the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The views expressed in this note are our own, and do not represent the views of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, nor any other person associated with the Federal Reserve System. We thank Shaghil Ahmed and Eva Van Leemput for helpful comments and suggestions. Return to text

2. How long it takes to return to the target depends on initial conditions and on the source and the severity of the shock (see Svensson 2010). Return to text

3. On studies looking at the advanced countries, see Gürkaynak, Levin, and Gürkaynak, Levin, Marder, and Swanson (2010) and Beechey, Johannsen, and Levin (2011). For EMEs, Gürkaynak, Levin, Marder, and Swanson (2006) examines the early evidence from Chile, and De Pooter, Robitaille, Walker, and Zdinak (2014) study the evidence from Brazil, Chile, and Mexico. Garcia and Werner (2024) find that for the euro area, far forward inflation compensation became more responsive to economic data releases after 2013. Return to text

4. Different sources were used to compile the inflation series, as detailed in Appendix 1. Return to text

5. Governments implicitly raised revenue through the inflation tax in various ways, such as by setting high required reserve ratios (Brock 1989). Return to text

6. See FitchRatings (2024), Capurro (2024), The Economist 2024, and the International Monetary Fund (2024a, 2024b). Brazil and Colombia last lost investment grade credit risk rating status in 2015 and 2021, respectively. Brazil's public debt to GDP ratio is projected be nearly 88 percent of GDP this year, one of the highest among the major emerging market economies and high for a country with a historical record of defaults. Return to text

7. Peru's inflation target was reduced from 2.5 to 2 percent in early 2007. Inflation targets have been occasionally changed in other countries, including Korea and Indonesia. Return to text

8. In late 2001, Banco de la República de Colombia (BanRep), announced that it intended to reduce inflation to a long-term goal of 3 percent (BanRep 2001), BanRep nonetheless continued to set annual inflation targets. Gómez-Pineda, Uribe, and Vargas (2002 p. 10) state that Colombia's inflation history and widespread indexation argued for a gradual disinflation "to maintain the society's support and avoid extremely high disinflation costs." According to Hamann, Hofstetter, and Urrutia (2014), BanRep was concerned, at times facing political pressures, about the need to build up its international reserves and limit upward pressures on the real exchange rate. Urrutia was BanRep's governor between 1993 and 2005 and Uribe served as BanRep's governor between 2005 and 2017. BanRep reduced the inflation target gradually from 10 percent for 2000 to 4 percent for 2008. In late 2008, the target was raised to 5 percent for 2009, a move that clearly reflected stabilization concerns. Return to text

9. For our purposes, it does not appear to matter that Consensus Economics surveys participants around the middle of the month, while the Bank of Mexico's conducts its survey in the last week of the month. Return to text

10. For Mexico, the standard deviation of long-term inflation forecasts in the Consensus survey peaked at 2.1 percent in the third quarter of 2018 (not shown in the figure). In the Bank of Mexico survey, the standard deviation doubled to 0.6 percent in the fourth quarter of 2017 and remained at or above that level through the third quarter of 2018. Return to text

Robitaille, Patrice, Tony Zhang, and Brent Weisberg (2024). "How Well-Anchored are Long-term Inflation Expectations in Latin America?," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, December 20, 2024, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3636.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.