FEDS Notes

January 08, 2020

Monetary Policy Space in a Recession: Some Simple Interest Rate Arithmetic

Summary

- Nominal interest rates are low in the United States and other advanced economies. Low nominal interest rates may constrain the ability of policymakers to provide accommodation through reductions in interest rates during an economic downturn.

- Model simulations have illustrated the magnitude of such constraints. Such results depend on modelling assumptions and can be difficult to understand. As an alternative, I present two recession scenarios in which interest rates change from October 2019 levels by the same amount as seen, on average, around the 1990 and 2001 recessions. These recessions were moderate by historical standards.

- In the scenarios, interest rates are at or below zero over maturities from one-day to seven or ten years. These paths are the result of the simple arithmetic underlying the scenarios. Negative interest rates have not been experienced in the United States and U.S. policymakers have emphasized alternative policy tools.

- Nonetheless, the scenarios illustrate that a recession may result in near-zero interest rates at long maturities, bringing U.S. experience closer to that seen in Europe and Japan. Such low levels of interest rates could imply limits on the ability of monetary policy to support a recovery.

Introduction

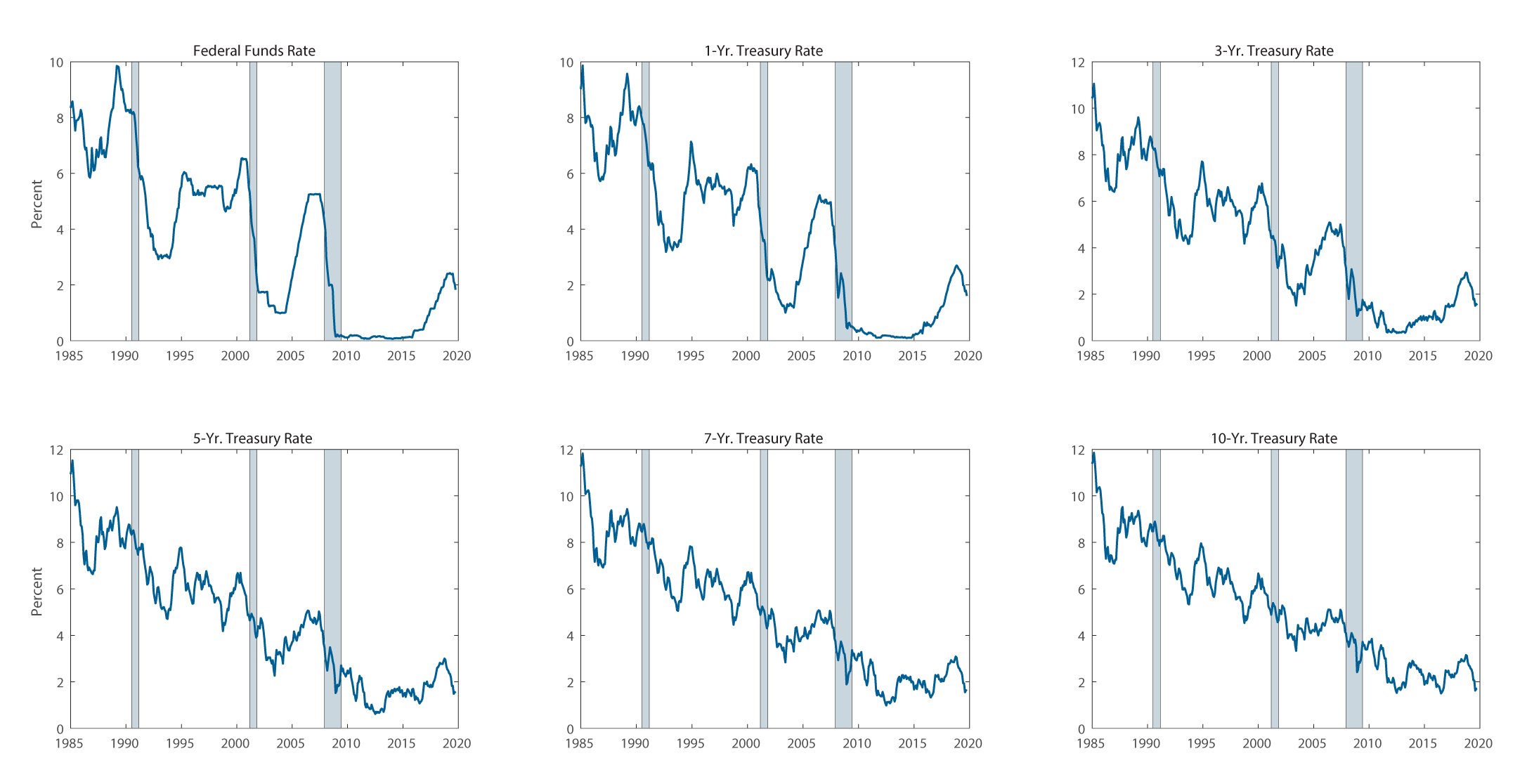

Nominal interest rates are low by historical standards. In October 2019, nominal interest rates from the overnight to a 10-year maturity averaged between 1.5 and 2 percent, as shown in figure 1. While interest rates at each maturity have been lower at some points in the past ten years, recent levels are very low by the standards of recent decades. Two important issues surface when considering the current level of rates. First, low interest rates are expected to persist for some time in the United States and in other advanced economies.2 Second, interest rates typically decline notably over the several years following a recession. This dynamic is apparent in the figure, with interest rates falling at all maturities in the years immediately following the 1990, 2001, and 2008-2009 recessions. The magnitude of declines in interest rates is sizable during each downturn. The magnitude of the declines across these recessions is significant even during the relatively moderate recessions experienced in 1990 and 2001. In other words, sizable and persistent declines in nominal interest rates following a downturn are not specific to large and persistent downturns such as that experienced following the Global Financial Crisis. Rather, such moves are the norm.

Note: Shaded regions indicate recessions as identified by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Source: Federal Reserve Board (retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis).

This typical behavior of nominal interest rates naturally raises two questions. The first is whether nominal interest rates may decline to historically unprecedented levels if another recession were to occur. The second is whether monetary policy would be constrained in its ability to provide support to a recovery, for example because nominal interest rates may face an effective lower bound near or somewhat below zero. Previous research has found a significant likelihood that short-term nominal interest rates would fall to their effective lower bound for an extended period and that such a constraint impedes economic performance a great deal (e.g., Kiley and Roberts, 2017; Bernanke et al, 2019; Reifschneider and Wilcox, 2019). However, these analyses used simulations of economic models, which involve a large number of technical assumptions that can be challenging for non-experts to understand. An alternative is simple scenario analysis that assumes a hypothetical future recession involving interest rate paths similar to those seen in earlier recessions. The following two sections lay out this approach and show the results.

Simple Interest Rate Arithmetic in Recession Scenarios

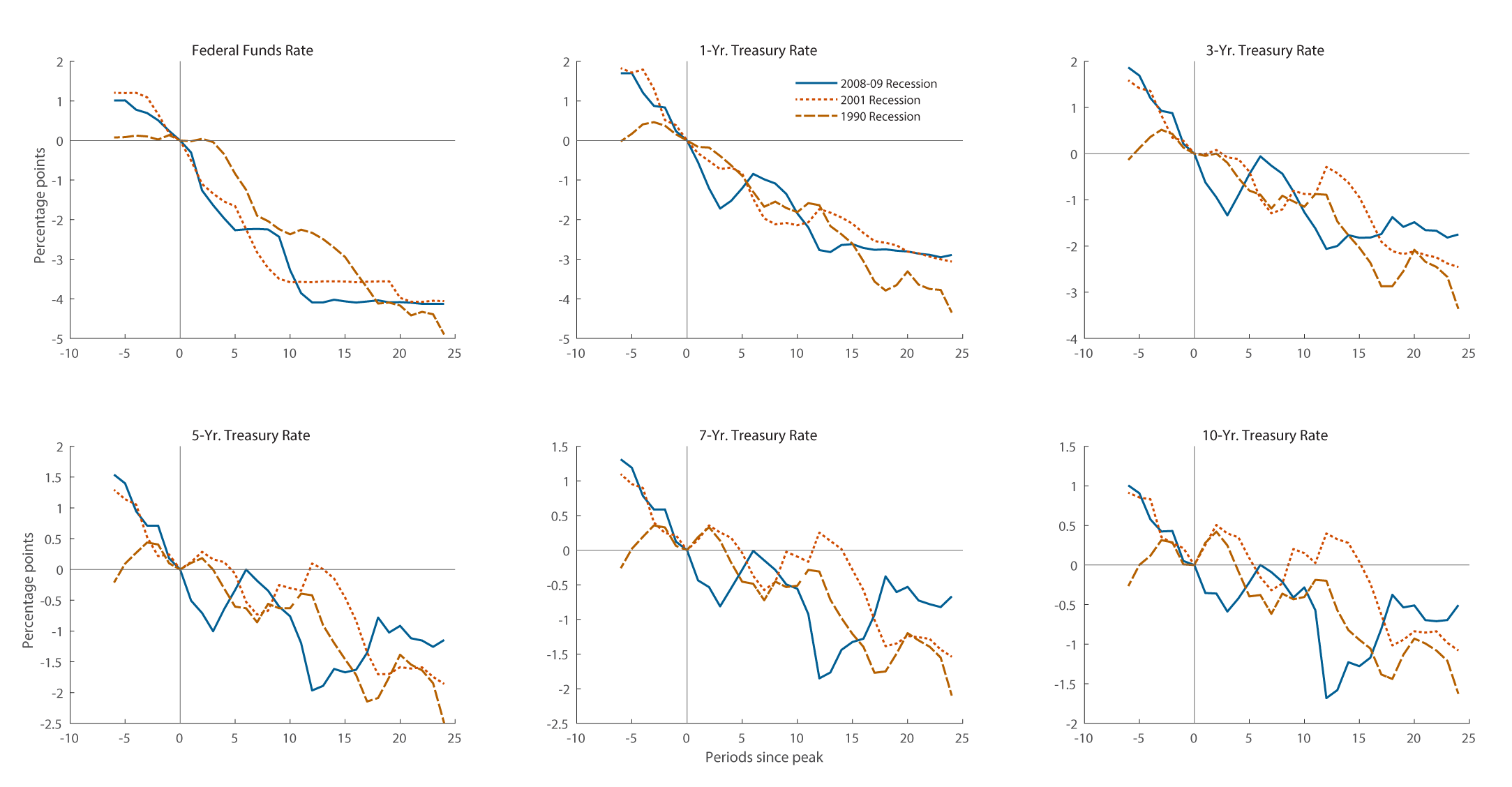

The approach is very simple. The first step involves characterizing potential paths of nominal interest rates in recession scenarios. As a start, figure 2 presents the paths of interest rates around the 1990, 2001, and 2008-2009 business-cycle peaks. Each line represents the level of the nominal interest rate relative to its level at the business-cycle peak (i.e., minus this level). For example, the path for the 2008-2009 recession is relative to the December 2007 level. The lines begin at period -6—i.e., six months before the business cycle peak—and end at period 24—i.e., two years after the peak. It is clear that interest rates for all maturities fall persistently following each recession. Indeed, the declines for maturities of three or more years are larger (in the second year following a recession) following the more moderate 1990 and 2001 recessions, which could indicate that declines in interest rates were constrained by effective-lower bound considerations following the more severe 2008-2009 recession. In addition, it is notable that interest rates begin declining as the business-cycle peak approaches, as the difference from the peak tends to be positive in the months preceding the onset of recession.

Source: Federal Reserve Board (retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis) and author's calculations.

Table 1 helps illustrate the quantitative magnitudes involved. First, the nominal federal funds rate tends to decline about 5 percentage points following a recession, as emphasized in Reifschneider (2016) and Reifschneider and Wilcox (2019). While declines are smaller for longer maturities, they remain sizable. For example, the average decline in the 10-yr. Treasury yield over the period from six months before the peak to two years after the peak over the 1990 and 2001 recessions was 1.7 percentage points. Given that nominal interest rates were between 1.5 and 2 percent in October 2019, these declines suggest that a recession scenario could involve negative to near-zero interest rates out to a 10-yr. maturity.

Table 1: Changes in Nominal Interest Rates Around Recent Business Cycle Peaks

| Federal Funds | Treasury Yields | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Yr. | 3-Yr. | 5-Yr. | 7-Yr. | 10-Yr. | ||||||||

| Months from business cycle peak | 0 to 24 | -6 to 24 | 0 to 24 | -6 to 24 | 0 to 24 | -6 to 24 | 0 to 24 | -6 to 24 | 0 to 24 | -6 to 24 | 0 to 24 | -6 to 24 |

| 1990, 2001, & 2008-2009 Recessions | -4.40 | -5.10 | -3.40 | -4.60 | -2.50 | -3.60 | -1.80 | -2.70 | -1.40 | -2.20 | -1.10 | -1.60 |

| 1990 & 2001 Recessions | -4.50 | -5.10 | -3.70 | -4.60 | -2.90 | -3.60 | -2.20 | -2.70 | -1.80 | -2.20 | -1.40 | -1.70 |

Source: Federal Reserve Board (retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis) and author's calculations.

The developments summarized in figure 2 and table 1 guide the construction of our recession scenarios. The construction involves three steps.

- Step 1: Define typical recession developments. I assume that interest rates follow the average paths, relative to the business-cycle peak, around the 1990 and 2001 recessions. This involves averaging the yellow and red lines in figure 2.

- Step 2: Define scenario 1. In the first scenario, I assume the business cycle peak occurred in October 2019. The scenario involves a path for interest rates in the 24 months following October 2019 equal to the average computed in step 1 for horizons from 1 to 24 months.

- Step 3: Define scenario 2. In the second scenario, I assume the business cycle peak occurs in April 2020, six months following October 2019. The scenario involves a path for interest rates in the 30 months following October 2019 equal to the average computed in step 1 for horizons from -6 to 24 months.

Results

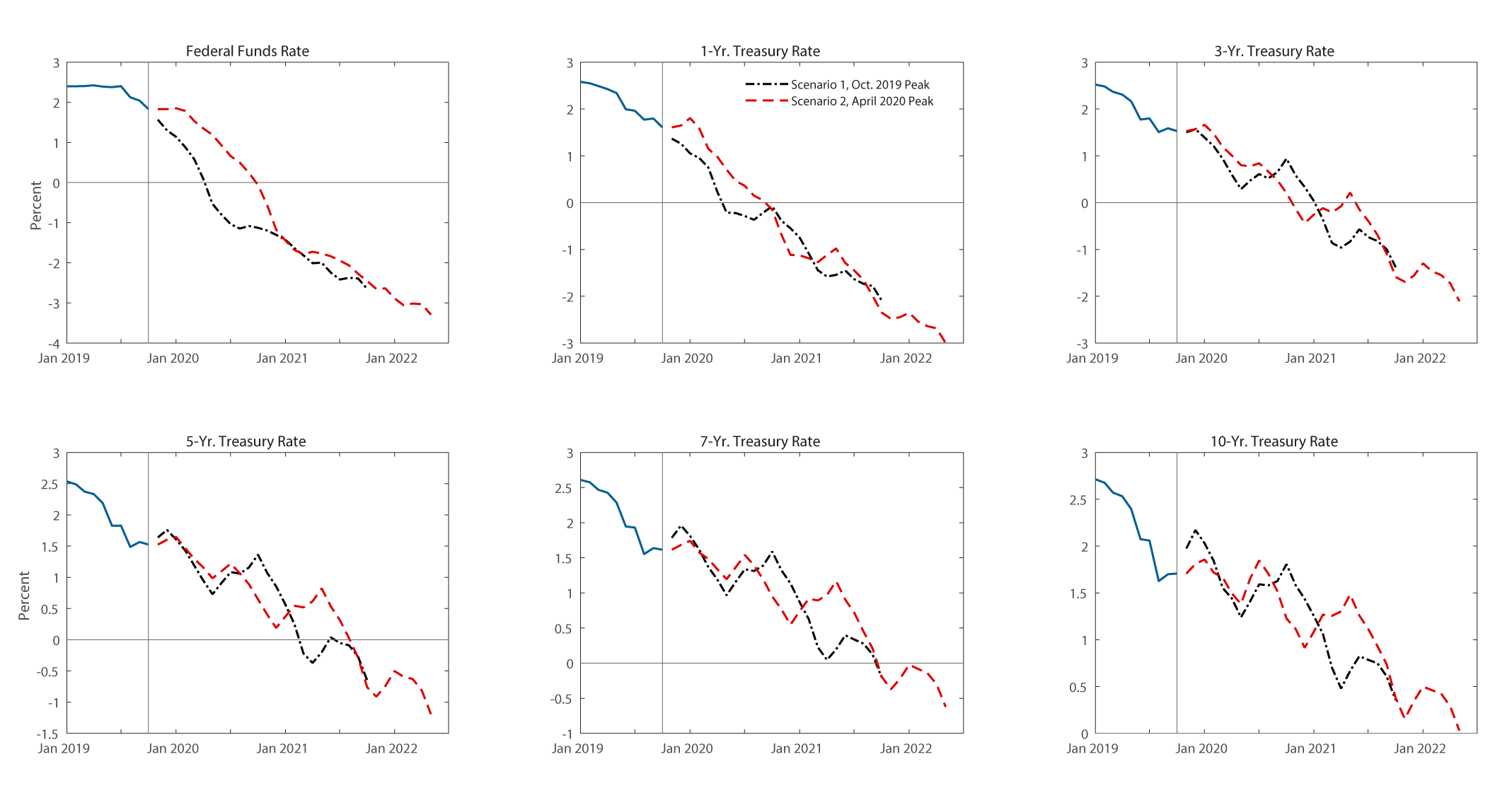

Figure 3 presents the results. In each scenario, the nominal federal funds rate falls to very negative values. Such negative values fall outside the range witnessed in the United States, Europe, or Japan. This is suggestive of a sizable constraint on monetary policy in these scenarios. More generally, the scenarios show Treasury yields below -1 percent at maturities up to five years. Rates this deeply negative have not been seen in advanced economies. Moreover, the scenarios involve rates that are negative out to seven years in both cases and a 10-yr Treasury yield of about zero percent in scenario 2 (involving a decline in the 10-yr. Treasury yield of 1.7 percent, as shown in the last column and row of table 2).

Source: Federal Reserve Board (retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis) and author's calculations.

Conclusions

I considered simple recession scenarios to illustrate the possible course of nominal interest rates in a recession. The scenarios are constructed using simple arithmetic and involve interest rates changing from October 2019 levels in a manner similar to that seen in the moderate recessions of 1990 and 2001. In the scenarios, interest rates are at or below zero over maturities from one-day to seven or ten years.

Negative interest rates have not been experienced in the United States and U.S. policymakers have emphasized alternative policy tools. Nonetheless, these scenarios highlight the possibility that a recession in the United States would bring nominal interest rates to unprecedented levels, potentially implying limits on the ability of monetary policy to support a recovery.

References

Bernanke, B. S., Kiley, M. T., & Roberts, J. M. (2019). Monetary Policy Strategies for a Low-Rate Environment. In AEA Papers and Proceedings (Vol. 109, pp. 421-26), May.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US) (2019), H.15 Selected Interest Rates, retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/release/tables?rid=18&eid=289#snid=324, November 12.

Kiley, M. T., & Roberts, J. M. (2017). Monetary policy in a low interest rate world. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2017(1), 317-396.

Kiley, M. T. (2019). The Global Equilibrium Real Interest Rate: Concepts, Estimates, and Challenges, Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2019-076. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, https://doi.org/10.17016/FEDS.2019.076.

Reifschneider, D. (2016). Gauging the Ability of the FOMC to Respond to Future Recessions, Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2016-068. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, http://dx.doi.org/10.17016/FEDS.2016.068.

Reifschneider, D. and D. Wilcox (2019). Average Inflation Targeting Would Be a Weak Tool for the Fed to Deal with Recession and Chronic Low Inflation. Petersen Institute for International Economics Policy Brief 19-16, November.

1. Federal Reserve Board. Email: [email protected]. The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect those of the Federal Reserve Board or its staff. Return to text

2. For a review of economic research in this area, see Kiley (2019). Return to text

Kiley, Michael T. (2019). "Monetary Policy Space in a Recession: Some Simple Interest Rate Arithmetic," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, January 8, 2020, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.2484.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.