FEDS Notes

December 18, 2020

Natural Disasters, Climate Change, and Sovereign Risk

Enrico Mallucci1

Introduction

Unexpected shocks may tip countries with elevated fiscal vulnerabilities into default. The literature has emphasized the role of macroeconomic and financial shocks, such as a decline of commodity prices (Reinhart et al., 2016) or banking crises (Baltenau and Erce, 2018) in shaping sovereign risk. However, other types of shocks, such as political events or natural disasters, are equally important.2 Extreme weather events appear especially salient in light of the key role played by natural disasters in recent sovereign default episodes (i.e. Grenada 2004, and Antigua y Barbuda 2004 and 2009), the climate crisis, and the recent emphasis on incorporating natural-disaster risk as a component of macroeconomic risk management. In particular, the increase in the frequency and intensity of natural disasters, has led several economists and policy makers to advocate in favor of adopting "disaster clauses" that allow for a temporary debt moratorium when countries are hit by catastrophic events.

This note highlights how the work of Mallucci (2020) speaks to the debate on natural disaster, climate change, and sovereign risk. Using a quantitative model of sovereign default, I study the impact of major hurricanes and climate change on governments' access to financial markets in a sample of seven Caribbean countries: Antigua y Barbuda, Belize, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Honduras, and Jamaica. I find that governments face worse borrowing terms due to hurricane risk and, consequently, reduce borrowings. Disaster clauses reduce the cost of issuing debt allowing governments to borrow more and preserving access to financial markets amid increasing risk of natural disasters and climate change. That said, debt limits may be needed in conjunction with disaster clauses to avoid overborrowing and a decline of welfare.

Recent Evidence

An inspection of recent sovereign default episodes shows that extreme weather has often played a prominent role, especially in small agricultural countries, where extreme weather events affect a vast portion of the territory. Moldova, Suriname, and Ecuador offer three neat examples. Moldova and Suriname defaulted respectively in 1992 and 1998 following severe droughts that weakened the production of agricultural export goods. Ecuador defaulted in 1997 just a few months after floods caused major power shortages.

The nexus between sovereign vulnerabilities and natural disasters is especially strong in Caribbean countries, as they are small and are regularly hit by tropical storms. On September 22 1998, the Dominican Republic was hit by hurricane Georges. The devastation brought by the hurricane was so extensive that the Dominican government had to seek support from the IMF and other official lenders in that very same year. Antigua y Barbuda shares a similar story. Following a series of hurricanes in the late '90s, the government began to accumulate arrears and ultimately defaulted in the early 2000s. Finally, the case of Grenada is emblematic. Between 1999 and 2002, Granada's fiscal position deteriorated sharply with the debt-to-GDP ratio reaching 80 percent. Grenada's fiscal position ultimately became unsustainable when hurricane Ivan hit the island in September 2004. Tourism and agriculture, the two major sources of export earnings, were especially hit, as the hurricane damaged infrastructure and wiped out the entire nutmeg crop. By the end of 2004, Grenada debt-to-GDP ratio stood at 130 percent, forcing the government to restructure its debt.

Sovereign risk and natural disasters are so interwoven in the Caribbean that governments have started to introduce bonds featuring disaster clauses that provide liquidity relief during catastrophic events. The government of Grenada led the way. In 2013, Grenada restructured its debt for the second time in a decade. A key feature of the restructuring event is that new bonds included a hurricane clause, allowing the government to delay debt repayments for up to one year in the event of a major hurricane. Since 2013 several other countries, including Mexico and Barbados, have followed Grenada's example.

Methodology

I extend the standard quantitative sovereign default model with long-term bonds as in Hatchondo and Martinez (2009) to include natural disasters in the form of major hurricanes. In every period, the model economy is subject to the risk of being hit by a hurricane. Hurricane damages are modeled as normally distributed shocks that reduce available income. The model is calibrated to replicate the behavior of seven Caribbean economies that are frequently hit by major hurricanes: Antigua y Barbuda, Belize, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Honduras, and Jamaica. In particular parameters determining the frequency and the intensity of disaster shocks are chosen to replicate the economic impact of major hurricanes in each of the seven countries. The comparison between the empirics (Panel A of Table 1) and model simulations (Panel B of Table 1) shows that the model is able to replicate well key moments from the data.

Hurricanes, Sovereign Risk, and Climate Change

To quantify the impact of hurricane shocks on sovereign risk, I solve a version of the model that eliminates hurricane risk and compare the results with the benchmark economy. Panels B and C in Table 1 compare average spreads, debt-to-GDP ratios, and default frequencies for each of the seven economies in our sample in the two scenarios. Absent hurricane risk, spreads and default frequencies are lower while debt-to-GDP ratios are higher. Countries that are more frequently hit by hurricanes, such as Antigua and Jamaica, benefit the most from the elimination of disaster risk. Altogether, these results clearly indicate that natural disasters negatively affect the governments' access to financial market.

With climate change, both the frequency and the intensity of natural disasters are expected to increase. Bhatia et al. (2018) project that the frequency of major hurricanes will increase 29.2 percent in the Atlantic by the end of the century and tropical cyclones will routinely reach wind speeds that are well above the category 5 threshold. The economic damages of hurricanes are poised to increase sharply. Acevedo (2016) for instance estimates that the economic cost of hurricanes will increase between 20 percent and 77 percent due to the intensification of wind speed.

Panel D in Table 1 reports key moments for the model economy in the climate change scenario that assumes, consistently with Bhatia et al. (2018), a 29.2 percent increase in the frequency of hurricanes and, consistently with Acevedo (2016), a 48.5 percent increase in their intensity, which is measured in terms of hurricanes' impact on income. Relative to the baseline scenario, spreads increase on average 30 percent and debt-to-GDP ratios decline 12 percent, indicating that climate change reduces the government's ability to borrow from abroad.

Table 1. Quantitative Analysis

Panel A: Moments from the Data

| Moment | Antigua | Belize | Dominica | Dominican Rep. | Grenada | Honduras | Jamaica |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Spread (bp) | 448 | 109 | 366 | 483 | 493 | 411 | 519 |

| Ext. Debt/GDP ratio | 0.36 | 0.78 | 0.56 | 0.25 | 0.53 | 0.35 | 0.49 |

| Default Frequency | 0.051 | - | 0.026 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.026 | 0.051 |

Panel B: Simulated Moments

| Moment | Antigua | Belize | Dominica | Dominican Rep. | Grenada | Honduras | Jamaica |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Spread (bp) | 466 | 143 | 378 | 497 | 499 | 423 | 526 |

| Ext. Debt/GDP ratio | 0.39 | 0.72 | 0.56 | 0.25 | 0.54 | 0.34 | 0.53 |

| Default Frequency | 0.044 | 0.014 | 0.033 | 0.04 | 0.047 | 0.028 | 0.043 |

Panel C: Simulated Moments - No Hurricanes

| Moment | Antigua | Belize | Dominica | Dominican Rep. | Grenada | Honduras | Jamaica |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Spread (bp) | 341 | 88 | 270 | 423 | 377 | 283 | 400 |

| Ext. Debt/GDP ratio | 0.51 | 1.04 | 0.63 | 0.28 | 0.6 | 0.38 | 0.67 |

| Default Frequency | 0.03 | 0.006 | 0.02 | 0.034 | 0.035 | 0.016 | 0.03 |

Panel D: Climate Change

| Moment | Antigua | Belize | Dominica | Dominican Rep. | Grenada | Honduras | Jamaica |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Spread (bp) | 655 | 185 | 494 | 591 | 613 | 618 | 658 |

| Ext. Debt/GDP ratio | 0.33 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.24 | 0.5 | 0.32 | 0.43 |

| Default Incidence | 0.057 | 0.017 | 0.044 | 0.047 | 0.056 | 0.045 | 0.057 |

Panel A reports key empirical moments for each of the seven Caribbean countries in my sample. Panel B reports moment obtained from the model economies. Panel C reports moment obtained eliminating hurricane risk. Panel D reports moments obtained increasing hurricanes' frequency 29.2 percent and hurricanes' intensity 48.5 percent.

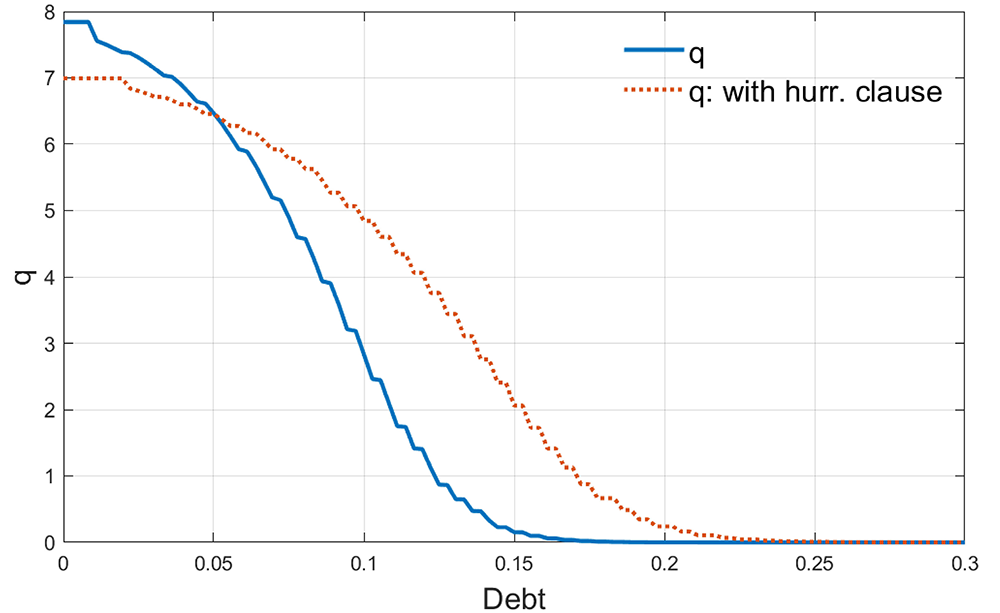

Disaster Clauses

To verify whether disaster clauses can effectively mitigate the impact of natural disasters on sovereign risk, I modify the theoretical model allowing governments to delay servicing debt whenever disasters hit. Figure 1 compares the price schedule q for Antigua y Barbuda's government bonds in the baseline scenario without disaster clauses (solid blue line) and in the scenario with such clauses (red dotted line).3 The price of government debt is generally higher in the scenario with disaster clauses, as they reduce default risk allowing governments to postpone payments when disasters hit. Only for very low levels of debt, the price of government bonds is higher in the baseline scenario than in the scenario with disaster clauses. For such low levels of debt, default risk is zero. Hence, while investors do not face any risk in the baseline scenario, they are subject to the risk of delayed repayments in the scenario with disaster clauses and need to be compensated accordingly. All told, Figure 1 suggests that borrowing terms generally improve with the introduction of disaster clauses.

The blue line plots the price schedule q for Antigua y Barbuda’s government bonds in the benchmark model. The red dashed line plots the price schedule q for Antigua y Barbuda’s government bonds in the model with the disaster clause.

Panel A of Table 2 reports key long-run moments for the economy with disaster risk. A comparison with Panel B of Table 1 shows that disaster clauses allow governments to borrow more and sustain higher debt-to-GDP levels. At the same time, however, spreads increase, despite the improvement of borrowing terms highlighted in the Figure 1 and the fact that the frequency of defaults remains stable. Together these results explain how governments modify their borrowing behavior following the introduction of hurricane clauses. Governments take advantage of the better borrowing terms and expand their borrowings up until the point that default risk reaches levels similar to those observed in the economy without disaster clauses. Spreads, however, are higher, as governments need to compensate investors for the risk of delayed repayments. Of note, the overall borrowing cost is little affected by the risk that repayments are delayed. Spreads increase due to delay risk, but the expected cost of servicing debt declines, as governments expect to postpone repayments. Hence, with the introduction of disaster clauses, governments tolerate higher spreads, as they have little impact on the overall borrowing costs.

Disaster clauses also affect the way governments modify their policies in response to climate change. Panel B of Table 2 shows that governments do not reduce their debt-to-GDP ratios amid climate change when there are disaster clauses. Moral hazard explains the result. With climate change, the frequency of hurricanes increases. Governments therefore engage in ``gambling for debt-servicing suspension'' behavior. They continue to issue high quantities of debt paying higher yields, as they expect to reduce the overall cost of borrowing activating the disaster clause more frequently. This result is in sharp contrast with the one presented in Table 1, showing that, absent disaster clauses, climate change reduces the government's ability to issue debt.

All told, our analysis indicates that disaster clauses can be an effective tool to preserve governments' access to financial markets, amid rising risk of natural disasters. However, they come with a cost, as they incentivize governments to borrow more and pay higher yields.

Table 2. Hurricane Clauses

Panel A: Simulated Moments - Hurricane Clauses

| Moment | Antigua | Belize | Dominica | Dominican Rep. | Grenada | Honduras | Jamaica |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Spread (bp) | 628 | 311 | 394 | 647 | 620 | 317 | 700 |

| Ext. Debt/GDP ratio | 0.57 | 1.33 | 0.6 | 0.29 | 0.65 | 0.39 | 0.76 |

| Default Incidence | 0.047 | 0.03 | 0.034 | 0.054 | 0.054 | 0.012 | 0.04 |

Panel B: Climate Change – Hurricane Clauses

| Moment | Antigua | Belize | Dominica | Dominican Rep. | Grenada | Honduras | Jamaica |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Spread (bp) | 962 | 506 | 436 | 697 | 720 | 332 | 883 |

| Ext. Debt/GDP ratio | 0.61 | 1.24 | 0.6 | 0.31 | 0.68 | 0.39 | 0.69 |

| Default Incidence | 0.039 | 0.025 | 0.018 | 0.036 | 0.045 | 0.003 | 0.036 |

Panel A reports moments obtained calibrating the model economy with the hurricane clause to each of the seven Caribbean economies in the sample, and simulating each economy for 9,500 periods. Panel B reports moments obtained increasing hurricanes' frequency 29.2 percent and hurricanes' intensity 48.5 percent.

Welfare Analysis and Debt Limits

Do disaster clauses increase welfare? To answer this question, I compute consumption-equivalent welfare changes required to make an agent in the disaster clause economy indifferent between that economy and the one without the disaster clause.4 Results are reported in Panel A of Table 3. Welfare equivalent consumption changes are negative implying that countries are worse off after the introduction of disaster clauses. This is true both in the baseline scenario and in the scenario with climate change. The explanation for this seemingly counterintuitive result lies in the fact that government debt is ex-ante optimal, but ex-post inefficient. At time t, governments want to borrow from abroad to boost consumption. However, in the following periods they regret past borrowings, as part of the income needs to be used to repay the debt. Sizable increases of the debt-to-GDP ratios, such as the ones reported in Table 2, are therefore associated with a decline of consumption and welfare.

The trade-off between the size of government debt and welfare, suggests that a combination of policies that reduce borrowing costs, such as disaster clauses, and keep debt levels under control, such as debt limits, may improve welfare over the cycle. I analyze the case of an economy that adopts hurricane clauses while simultaneously capping government debt to the levels observed in the economy without them. Welfare gains for such economy (Panel B of Table 3) are positive, confirming the intuition that debt limits must be introduced together with disaster clauses to avoid a decline in welfare.

All told, the welfare analysis shows that disaster clauses, while effective at preserving governments' access to financial markets, may induce overborrowing. Debt limits, are needed to avoid a decline of welfare.

Table 3. Welfare Analysis

Panel A: Welfare Analysis - Disaster Clause

| Moment | Antigua | Belize | Dominica | Dominican Rep. | Grenada | Honduras | Jamaica |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆WC | -2.76% | -7.09% | -0.96% | -1.22% | -1.60% | -1.57% | -1.41% |

| ∆WC,CC | -2.87% | -11.56% | -0.82% | -1.21% | -1.75% | -2.10% | -2.18% |

Panel B: Welfare Analysis - Disaster Clause and Debt Limit

| Moment | Antigua | Belize | Dominica | Dominican Rep. | Grenada | Honduras | Jamaica |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆WC | 2.02% | 3.63% | 0.26% | 1.34% | 1.06% | 1.19% | 1.87% |

| ∆WC,CC | 2.10% | 3.10% | 0.06% | 1.28% | 0.93% | 0.50% | 1.84% |

Panel A reports consumption equivalents that make agents indifferent between the economy featuring disaster clauses and the economy without them. ∆WC are consumption equivalents computed in the baseline scenario. ∆WC,CC are consumption equivalents computed in the economy with climate change. Panel B reports consumption equivalents that make agents indifferent between the economy with disaster clauses and debt limits and the economy without neither.

References

Arellano, Cristina, Yan Bai, and Gabriel Mihalache, "Deadly Debt Crises: COVID-19 in Emerging Markets," Staff Report 603, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis May 2020.

Balteanu, Irina and Aitor Erce, "Linking Bank Crises and Sovereign Defaults: Evidence from Emerging Markets," IMF Economic Review, December 2018, 66 (4), 617–664.

Bhatia, Kieran, Gabriel Vecchi, Hiroyuki Murakami, Seth Underwood, and James Kossin, "Projected Response of Tropical Cyclone Intensity and Intensification in a Global Climate Model," Journal of Climate, 2018, 31.

Hatchondo, Juan Carlos and Leonardo Martinez, "Long-duration bonds and sovereign defaults," Journal of International Economics, September 2009, 79 (1), 117–125.

Mallucci, Enrico, "Natural Disasters, Climate Change, and Sovereign Risk," International Finance Discussion Papers 1291, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.) July 2020.

Reinhart, Carmen M., Vincent Reinhart, and Christoph Trebesch, "Global Cycles: Capital Flows, Commodities, and Sovereign Defaults, 1815-2015," American Economic Review, May 2016, 106 (5), 574–580.

1. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washing, D.C. 20551 U.S.A.. E-mail: [email protected] Return to text

2. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is also an example of a disaster that may exacerbate existing fiscal weaknesses as highlighted by the recent work of Arellano et al (2020) Return to text

3. The price schedules of the other economies are similar. Return to text

4. Formally, let $$c^{\ast}$$ equilibrium consumption in the benchmark economy and let $$c^{\ast}_{WC}$$ be equilibrium consumption with disaster clauses. The consumption welfare change $$\Delta_{WC}$$ that makes agent $$i$$ indifferent between the two scenarios solves: $$W(c^{\ast}(1+\Delta_{WC}) = W(c^{\ast}_{WC})$$.

Symmetrically, let $$c^{\ast,CC}$$ equilibrium consumption in the benchmark economy with climate change and let $$c^{\ast,CC}_{WC}$$ be equilibrium consumption with disaster clauses in the climate change scenario. The consumption welfare change $$\Delta_{WC,CC}$$ that makes agent $$i$$ indifferent between the two scenarios solves: $$W(c^{\ast,CC}(1+\Delta_{WC,CC})) = W(c^{\ast,CC}_{WC})$$.

Mallucci, Enrico (2020). "Natural Disasters, Climate Change, and Sovereign Risk," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, December 18, 2020, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.2813.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.