FEDS Notes

February 14, 2025

Proportionate margining for repo transactions

R. Jay Kahn and Matthew McCormick

Introduction

The repurchase agreement (repo) market plays a central role in funding and leveraging securities positions, and sourcing securities. Traders in the repo market protect themselves from the default of their counterparties through margin collected via haircuts on repo transactions. Since the purpose of margin is to protect a firm from the default of a counterparty, when set appropriately these margins accurately reflect the risk and costs of counterparty default.1 Recent research showing that haircuts on many Treasury repo transactions are low or zero has raised concerns that margining practices in this market are insufficiently strict. These low haircuts are seen as encouraging highly leveraged positions in the Treasury market, which might exacerbate disruptions in the Treasury market such as those experienced in March 2020.

We consider the problem of setting appropriate margins on repo contracts. In our discussion below we leave aside the appropriate level of margin on repo transactions to focus on the form that margin collection takes. We consider margining of individual transactions, portfolios of repo transactions and portfolios of repo and derivatives transactions. Using these examples of common use-cases, we show that best practices for margining on repo should:

- provide appropriate net protection to all of the participants in a transaction,

- reflect both counterparty and collateral risk,

- take into account the full portfolio of exposures between counterparties.

We call margins that satisfy these principles "proportionate margins" since they align margins with the size of default risk. Along the way, we highlight occasions on which existing practice in non-centrally cleared repo markets does not adhere to these principles and provide an illustrative framework for how proportionate margining could be achieved. We find discussions of haircuts in Treasury repo can be informed by best practices in other markets for margining, including netting of exposures and (where practicable) cross-margining.

One proposal for raising margins and cutting down on leverage in the Treasury market has been for regulators to impose minimum haircuts.2 Minimum haircuts are thought to be advantageous in part as a means of controlling leverage while providing congruence: that is, treating similarly risky trades similarly. Higher haircuts could restrict leverage by requiring traders to keep more cash with their dealer for every dollar of securities exposure—though the extent to which overall leverage would be limited depends on whether current haircuts are a binding constraint on leverage.3

We consider this proposal but show that in many cases minimum haircuts would not lead to proportionate margining, and therefore could decrease liquidity in repo and securities markets without offering a substantial increase in protection. For instance, minimum positive haircuts could deny protection to dealers in trades where haircuts are typically negative because hedge funds are lending in repo to source specific securities. Meanwhile, in trades involving a portfolio of offsetting exposures, by not taking these offsets into account minimum haircuts could impose costs disproportionate to the risks involved in the trade, undermining the benefits of minimum haircuts for congruence. We discuss how proportionate margin schemes that borrow from the state-of-the-art in margining practices could be structured to increase protection for repo counterparties with a lesser impact on market liquidity.

Existing repo margining practices in the U.S.

Margining practices in the U.S. repo market differ significantly depending on whether a transaction is centrally cleared or non-centrally cleared, although transactions across both segments are generally similar in form.4 The Fixed Income Clearing Corporation (FICC) currently serves as the central counterparty for all centrally cleared repo in the U.S., clearing both trades between clearing members (largely dealers and banks) and trades between clearing members and some non-members like money market funds and hedge funds. Outside of central clearing, the non-centrally cleared market is split into two segments. The first is the tri-party repo market for which the Bank of New York serves as custodian, where typically banks and money market funds lend cash to dealers against general collateral.5 The second is the non-centrally cleared bilateral market (NCCBR), where trades are cleared and settled without a central counterparty or custodian. Activity in this market largely consists of dealers lending to hedge funds, and unlike tri-party, this market can be used to borrow specific securities.6

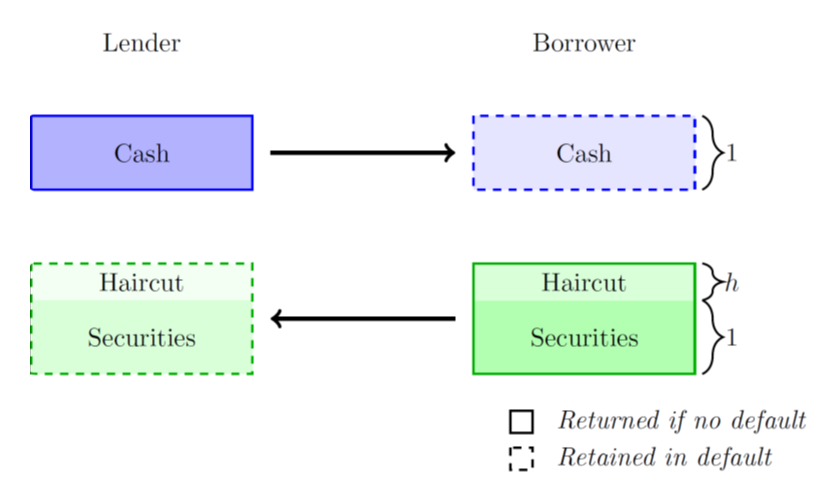

In non-centrally cleared markets, margin is determined bilaterally between participants and takes the form of overcollateralization, also known as haircuts. Repo is a temporary exchange of cash for securities; without a haircut, at the start of the trade the cash borrower receives cash equal to the value of securities it posts as collateral. As shown in Figure 1, a positive haircut means that the cash borrower posts collateral with value exceeding the cash it receives, so that if the borrower defaults the cash lender is likely able to liquidate the collateral posted to it and recover its original position without loss. This reflects the fact that in non-centrally cleared repo, margin is driven primarily by relative counterparty credit quality, and secondarily by potential changes in the value of collateral.

Note: This figure shows a transaction with a positive haircut of $$h$$, implying that the value of securities provided exceeds the value of cash with $$1+h$$ dollars of securities to every dollar of cash.

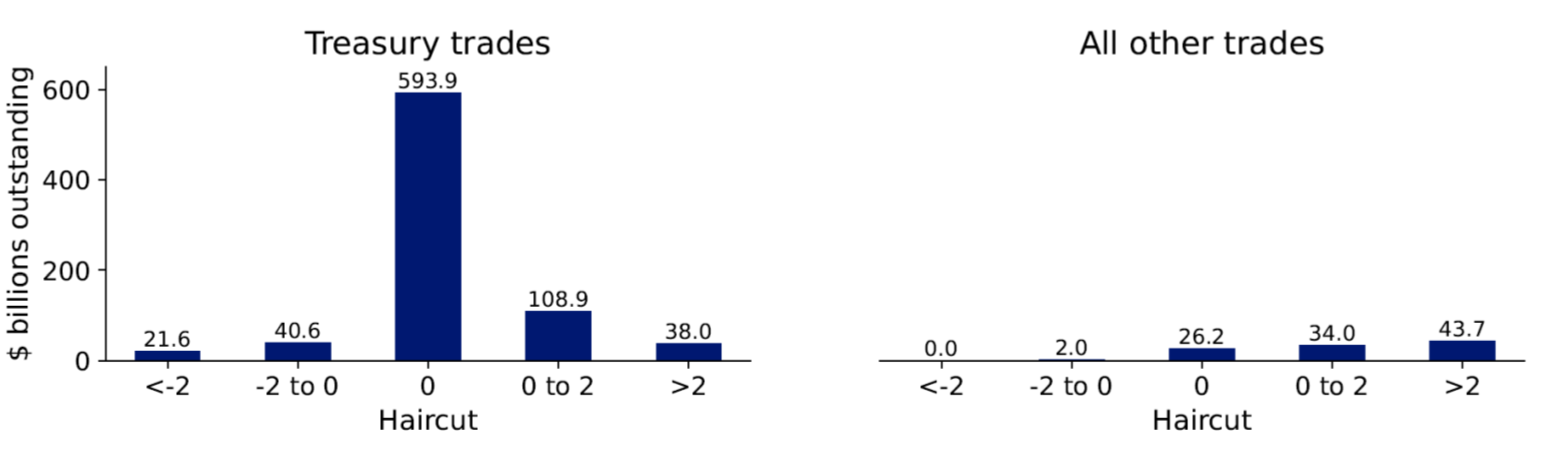

Recent evidence shows that haircuts differ greatly between the two non-centrally cleared markets. Tri-party repo haircuts for Treasury collateral have long hovered almost uniformly around 2%, as indicated by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York's Tri-party Statistics. Until recently, however, little was known about haircuts in NCCBR. Hempel et al. (2023b) used data from the Office of Financial Research's pilot collection to show that around 70% of Treasury transactions in this market segment are conducted without a haircut, implying cash lent in these repos is equal to the value of collateral transferred.7 Moreover, as shown in Figure 2 below, their results show that just under 10% of Treasury volumes in this market are transacted with a negative haircut, implying cash lent is larger than the value of the collateral.

Source: Hempel et al. (2023b).

In centrally cleared repo, margin for trades between clearing members is determined by the central counterparty (CCP), which relies on a risk-based model—a form of Value-at-Risk (VaR)—to set margins. Notably, this margin is not the sole source of protection against counterparty risk in centrally cleared repo, since CCPs also establish minimum standards for direct clearing members and require clearing fund contributions that may be indexed to counterparty risk. As a result, margining in non-centrally cleared repo is fundamentally more complicated than margining of clearing members by a CCP since margins in non-centrally cleared repo must account for the heterogeneous riskiness of borrowers as well as the riskiness of collateral.

However, while trades between clearing members are subject to margining by the CCP, trades between direct clearing members and customers are often effectively margined bilaterally. Margin is charged to the direct clearing member by the CCP based on their position with customers, but the CCP does not collect margin directly from the customer.8 Instead, the clearing member is left to collect margin from their customer as they see fit, and anecdotal evidence suggests margining practices here are similar to non-centrally cleared repo.9 Therefore, while much activity is likely to move from non-centrally cleared to centrally cleared repo as part of the implementation of the SEC's central clearing rule, margining practices may not change substantially for a large portion of the market.

Proportionate margins

The problem of appropriate margining is an important one for both market participants and regulators. Low margins leave the firm unprotected and may lead to excessive risk taking. High margins impair liquidity and may encourage regulatory avoidance.

Margins should therefore be proportionate: the cash held against an exposure should reflect the associated risk. If margins are disproportionate and similarly risky exposures are margined differently, it encourages risks to build up in counterparties or trades that are treated favorably. Proportionate margins should also be consistent dynamically. If volatility increases or positions become larger or more concentrated, margins must rise to adequately protect the firm. If, instead, margins increase without an increase in risk, the sudden demand for cash from a counterparty may force the firm to offload securities at fire-sale prices. In the aggregate, this behavior can present a risk to financial stability as many firms offloading securities could lead to a "margin spiral," where prices fall and lead margins to rise for other firms, kicking off a vicious cycle of price decreases, margin increases and forced sales.10

These principles are not new and are in fact consistent with acknowledged best practices in other markets. For instance, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision Board's "Margin requirements for non-centrally cleared derivatives" states that margining practices should be consistent across entities and generally reflect the portfolio of exposures in between counterparties.11 Meanwhile, in cleared markets, our approach is generally consistent with requirements set by the SEC for margining at CCPs which include an "appropriate method for measuring credit exposure that accounts for relevant product risk factors and portfolio effects across products."12 Our discussion of proportionate margining also mirrors the discussion of "risk-based" margining for CCPs in Cox et al. (2016). Finally, while we make no attempt to describe optimal margins, proportionate margins are consistent with models of optimal margin setting such as Baer et al. (2004), where these margins are set by a trade-off between losses due to default and the opportunity costs of funds tied up as margin.

Margining individual repo transactions

We now turn to the issue of how to use haircuts to set margins in bilateral repo that are proportionate to the risk of a counterparty's default — on both sides of the trade. If the borrower in a repo defaults, the lender is left holding securities that may have fallen in value. But conversely, if the lender defaults, the borrower retains the cash but loses the posted securities, which may have risen in value. Thus, from the lender's perspective, the repo creates a long exposure to the collateral; from the borrower's perspective, it creates a short exposure. Both parties face risk, and a proportionate haircut on a repo will provide appropriate net protection to the lender, since the haircut is paid to the lender by the borrower. Crucially, in non-centrally cleared repo the use of haircuts for protection is essentially zero sum: since there is no trusted third-party like a CCP to collect gross margins, higher haircuts can only protect the lender by taking protection away from the borrower.

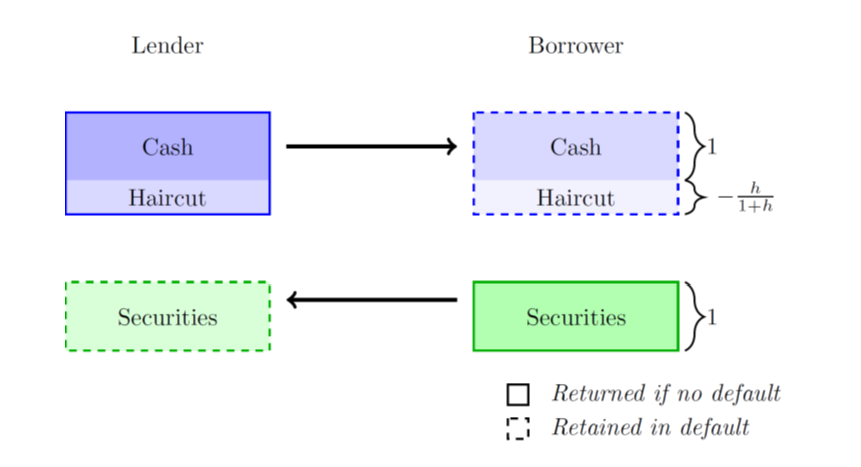

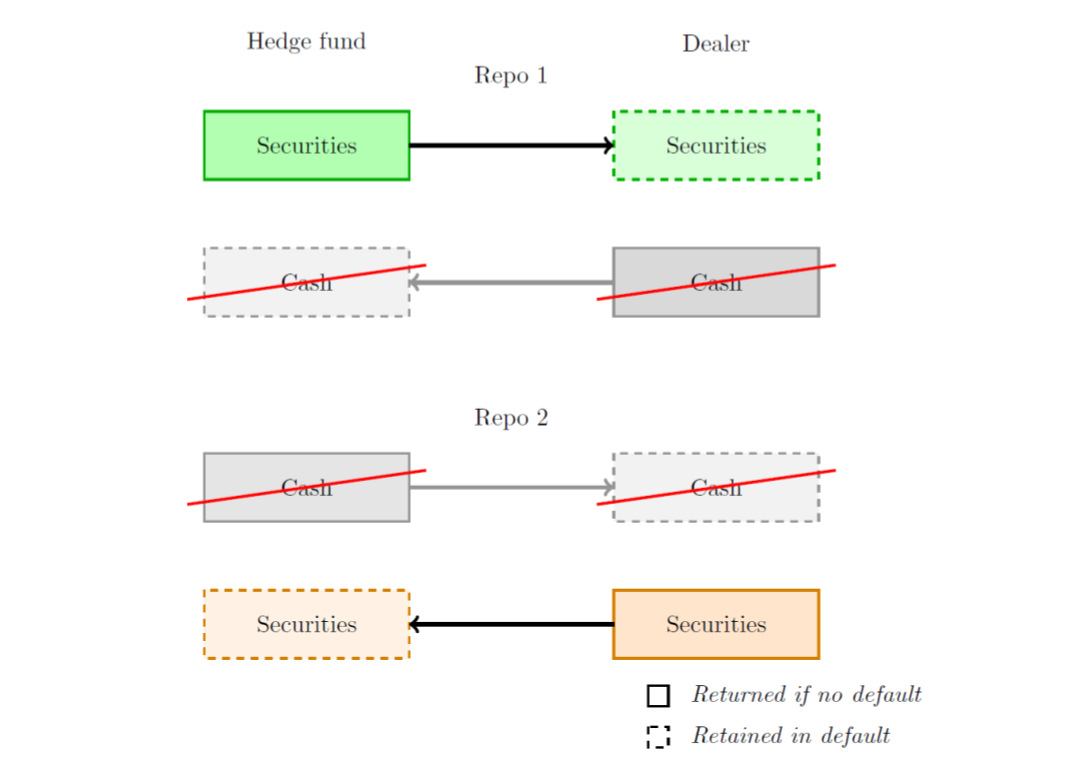

As a result, for many repo transactions a minimum haircut may not provide proportionate margins. Minimum haircuts ensure a lender is provided net protection against the borrower's default, but it is often the borrower who needs protection — particularly when the lender is the riskier party. In this case, the risk to the borrower of losing a valuable security may outweigh the risk to the lender of losing cash. For instance, hedge funds often lend cash to dealers through repo to obtain specific securities to short. In this case, it is the dealer who needs protection from a risky lender. As a result, many haircuts for non-centrally cleared repo are negative when hedge funds lend to dealers. As in Figure 3, this means more cash flows from the hedge fund to the dealer to protect them against losing a valuable security. A minimum (positive) haircut would undermine proportionate margining in this case by instead forcing a transfer from the dealer to the hedge fund. As a result, dealers might be less willing to provide specific securities to hedge funds, diminishing liquidity and price discovery in the Treasury market.

Note: This figure shows a transaction with a negative haircut of $$h$$, implying that the value of cash provided exceeds the value of securities with $$1-h/(1+h)$$ dollars of cash to every dollar of securities (this is mathematically equivalent to $$1+h<1$$ dollars of securities to every dollar of cash as in Figure 2).

Proportionate haircuts for individual repo transactions need to reflect both the riskiness of the counterparty and the volatility of the collateral.13 For illustration, consider a transaction where the lender has a probability of default $$q$$ and the borrower has a probability of default $$p$$. The security used as collateral has a random return of $$r$$. If the borrower defaults, the lender holds the collateral (a long position). If the lender defaults, the borrower is effectively short the collateral. One way to set margins proportionately would be through a Value-at-Risk (VaR) framework. In this case the haircut would be:

$$$$h=-p\times\ r_\theta-q\times\ r_{1-\theta}$$$$

where $$r_\theta$$ is the $$\theta-percentile$$ of the collateral's return distribution, with $$r_\theta$$ generally negative and $$r_{1-\theta}$$ generally positive.14 The first term ($$-p\times\ r_\theta$$) is the gross $$\theta-percent$$ VaR margin for the lender's exposure to the borrower. The second term, ($$q\times\ r_{1-\theta}$$) is the gross $$\theta-percent$$ VaR margin for the borrower's exposure to the lender. The sign and magnitude of the haircut under this scheme depend on both the relative risk of the borrower and lender and the distribution of returns for the collateral. Meanwhile, if margins are deemed by regulators to be too low to account for spillovers from default, they can be increased while retaining proportionality across trades by lowering $$\theta$$.

As these examples illustrate, comparisons of bilateral haircuts to the 2% haircuts in tri-party repo are misleading. In the tri-party market dealers are borrowing from relatively safe counterparties like money market funds and depository institutions, so on net it is the lenders who need protection.15 Furthermore, since tri-party is a general collateral market, dealers usually use low-value collateral they are not concerned about losing.16 Finally, regulatory requirements for MMFs that repo be "collateralized fully" (inclusive of both the value of the security and transaction costs incurred in its sale) in order to qualify as an investment in the underlying security may be interpreted by MMFs to effectively require a positive haircut. Therefore, the fact that 2% haircuts are common in tri-party says little about appropriate haircuts for other types of repo. Indeed, uniformity of 2% haircuts in tri-party — regardless of market conditions or counterparty — may reflect that MMFs prefer a simple, convenient approach rather than truly risk-adjusted margins.

Margining a portfolio of repo transactions

When multiple repo transactions are linked (e.g., under a master netting agreement), proportionate margins should account for the total portfolio exposure, rather than just one transaction in isolation. For example, if a customer defaults on one repo transaction, agreements often allow the dealer to treat the customer as in default on all outstanding repos. In this case, the relevant risk is the entire portfolio, not just a single transaction. The portfolio risk may be higher than the risks of individual transactions because of concentration risk, or lower because of offsetting exposures. Proportionate margins should reflect this.17

As an example of this principle, consider margining of "netted packages," a portfolio that makes up over 60% of trading by hedge funds in non-centrally cleared bilateral repo, and is covered in depth in Hempel et al. (2023b). In a netted package, a dealer both lends and borrows cash with a single counterparty at the same time, but with different collateral. As shown in Figure 4, because there is no net transfer of cash, the main risk is that the collateral received could depreciate relative to the collateral given away. The risk therefore stems from changes in the spread between these two securities' values. If those securities move in tandem, the spread is small; if they diverge, the spread can widen.

Note: This figure shows an example of a netted package, where the cash legs of two repos offset each other, resulting in a temporary swap of securities.

A minimum haircut on each leg of a netted package would not be proportionate to the spread risk between the two securities and would have little net effect, since the cash in the trades offset. For example, if both legs carry a 2% haircut, the dealer receives 2% of the collateral's value on the reverse repo but returns it on the repo, yielding a net haircut of zero on the entire package. Nor would assigning a 2% haircut to one leg and –2% to the other solve the problem, as it fails to account for how collateral values may correlate or diverge across the two legs. Consequently, neither arrangement provides proportionate protection against adverse moves in the spread.

Instead, proportionate margins should reflect the risk posed by adverse moves in the value of collateral. This implies that margin should generally be collected on netted packages. Meanwhile, when the values of the two collateral legs are correlated, expected losses resulting from customer default are lower. Proportional margins should also take this offsetting risk into account.

Where master netting agreements are in place, proportionate margins can be implemented through the use of "portfolio margining." 18 Portfolio margining allows a firm to consider the full set of exposures and offsets from transactions with each counterparty, rather than margining each exposure separately. Concretely, if a dealer has a portfolio of collateral with a counterparty, the dealer can model the portfolio return as:

$$$$\hat{r}=\sum_{i}\ w_ir_i$$$$

where $$w_i$$ is the weight of each collateral $$i$$, and return $$r_i$$ is the return on that collateral (with the sign of $$w_i$$ reflecting whether the dealer is lending or borrowing). The average haircut on these transactions could then be determined as above by calculating a $$\theta-percent$$ VaR over this portfolio and applying to it the probabilities of borrower and lender default. This is a natural extension of the idea that the risk of repo is fundamentally the creation of long and short positions in the underlying collateral in default.

We can apply this notion to netted packages by considering just two securities, with weights $$w_1=-w_2=1$$. The portfolio level return is then equal to the spread between the return on securities 1 and 2, $$s$$. If the dealer has a risk of default of $$p$$, and the hedge fund has a risk of default $$q$$, a proportionate net margin towards the dealer on these two transactions would be:

$$$$h=-p\times\ s_\theta-q\times\ s_{1-\theta}$$$$

Note that this formula for proportionate margins would not lead to zero haircuts on netted packages, since both the risk of the collateral and the probabilities of default will not usually cancel out in the above equation. As above, more stringent margining practices could be easily applied while retaining proportionality by simply lowering $$\theta$$ and taking account of deeper potential losses.

Margining portfolios across products

When repo transactions are paired with futures or other derivatives, cross-margining can extend the principle of proportionate margins across multiple products.19 Cross-margining accounts for offsets between products, but in general should be applied with caution since it works best for trades where the relationships between the products involved are well understood.

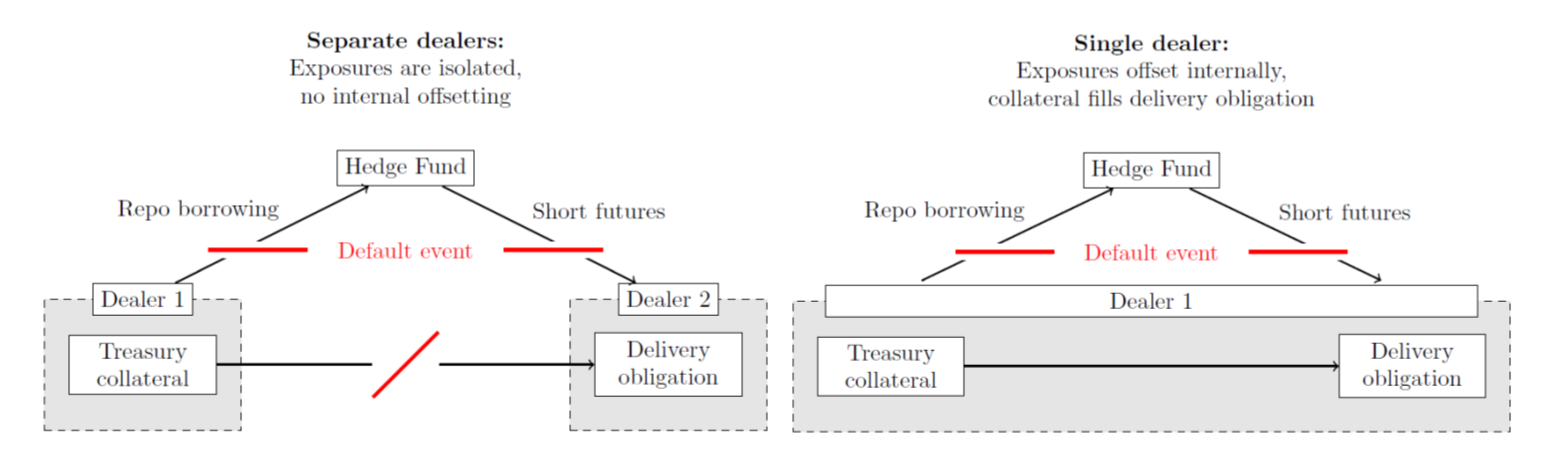

A prime example of a trade where cross-margining can lead to more proportionate margins is the cash-futures basis trade. In this near-arbitrage trade a Treasury is financed in repo and held to be delivered into an outstanding futures contract.20 Because the collateral that secures the repo also meets the futures delivery obligation, these two exposures offset in default if they go through the same dealer, as illustrated in Figure 5.21 Recognizing that these positions can offset in the event of a default leads to more proportionate (and lower) margin requirements than if each leg were viewed in isolation.

Some observers worry that cross-margining basis trades might encourage excessive leverage by lowering effective haircuts on one or both legs of the trade. However, one of the principal risks to the trade comes from increases in margin when volatility is high.22 Accounting for offsets involved in the trade means the odds and extent of these margin calls is greatly reduced, which can make the trade safer.

Conclusion

Designing an effective margining framework for the repo market requires balancing two critical objectives: protecting firms against counterparty default and allowing them to trade at low cost. These objectives can be in tension, so a well-structured margin regime should ensure lower-risk trades are not unnecessarily burdened while higher-risk trades remain properly collateralized. Therefore, margins should be proportionate to the counterparty risk involved in a trade. We lay out some principles of "proportionate" margining that rely on best practices recognized for margining in other markets, such as portfolio margining and cross-margining. We also show that minimum haircuts would often fail to meet this standard, because they either impose excessive collateral requirements on relatively low-risk exposures or leave high-risk positions under-margined.

We propose an illustrative approach to proportionate margining grounded in VaR-based portfolio margining. This approach shares several features with the margining framework currently employed by centrally cleared repo markets. One advantage of adopting a similar approach for non-centrally cleared repo would be providing greater congruence in practices between these two segments.

A reason that flexible proportionate margin approaches such as VaR techniques may currently be unpopular is the data and modelling required to implement them. Expansion of central clearing under the SEC's rule mandating clearing of Treasury repo provides an opportunity for regulators and market participants to more easily provide proportionate margins in dealer-to-customer trades. Once the rule goes into full effect, most trades are likely to be novated to FICC. Therefore, even if a CCP does not directly margin both sides of the trade—such as in many dealer-to-customer transactions—it will still have full visibility into the terms of each transaction. A CCP could therefore harness its margining expertise and data resources to provide a service that recommends proportionate margin levels for customers based on the collateral to their trades, allowing dealers to limit their decisions to counterparty risk. This provides one possible avenue for regulators and market participants to advance a comprehensive, consistent framework for margining the repo market - one that fosters both liquidity and stability.

Bibliography

Banegas, Ayelen, and Phillip Monin (2023). "Hedge Fund Treasury Exposures, Repo, and Margining," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, September, 08, 2023.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and the International Organizations of Securities Commissions, 2020. "Margin requirements for non-centrally cleared derivatives."

Herbert L. Baer, Virginia G. France and James T. Moser, 2004. "Opportunity cost and prudentiality: An analysis of collateral decisions in bilateral and multilateral settings (PDF)," Research in Finance, (21), pp. 201-227.

Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems and Technical Committee of the International Organization of Securities Commissions, 2012. "Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures (PDF)."

Adam Copeland and R. Jay Kahn, 2024. "Repo Intermediation and Central Clearing: An Analysis of Sponsored Repo," Staff Reports 1140, Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Robert Cox, Richard Heckinger and David A. Marshall, 2016. "Cleared Margin Setting at Selected Central Counterparties," Economic Perspectives, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, issue 4.

Group of 30 Working Group on Treasury Market Liquidity, "U.S. Treasury Markets: Steps Toward Increased Resilience (PDF)" (2021).

R. Jay Kahn and Vy Nguyen, 2022. "Treasury Market Stress: Lessons from 1958 and Today," Briefs 22-01, Office of Financial Research, US Department of the Treasury.

Paul H. Kupiec, 1997. "Margin requirements, volatility, and market integrity: what have we learned since the crash?"

Samuel J. Hempel, Calvin Isley, R. Jay Kahn and Patrick E. McCabe, 2023a. "Money Market Fund Repo and the ON RRP Facility," FEDS Notes 2023-12-15-2, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.).

Samuel Hempel, R. Jay Kahn, Robert Mann and Mark Paddrik, 2023b. "Why is so much repo not centrally cleared? (PDF)" Briefs 23-01, Office of Financial Research, US Department of the Treasury.

Infante, Sebastian, 2019. "Liquidity windfalls: The consequences of repo rehypothecation," Journal of Financial Economics, Elsevier, vol. 133(1), pages 42-63.

Miruna-Daniela Ivan, Joshua Lillis, Eduardo Maqui and Carlos Cañon Salazar, 2024. "'No one length fits all' — haircuts in the repo market," Bank Underground, Bank of England.

Mark Paddrik, Carlos Ramirez and Matthew McCormick, 2021. "The Dynamics of the U.S. Overnight Triparty Repo Market," Briefs 21-02, Office of Financial Research, US Department of the Treasury.

Chase P. Ross, 2022. "The Collateral Premium and Levered Safe-Asset Production," Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2022-046, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.).

Lester G. Telser, 1981 "Margins and Futures Contracts," Journal of Futures Markets 1.2.

Joshua Younger, 2021. "Cross-Margining and Financial Stability," Yale Program on Financial Stability Blog, June 22, https://som.yale.edu/blog/cross-margining-and-financial-stability

1. Economists have had this understanding of the role of margin for many years, see for example Tesler (1981). Return to text

2. For example, the G30 report on Treasury Market Liquidity notes: "In principle, if all repos were centrally cleared, the minimum margin requirements established by FICC would apply market wide, which would stop competitive pressures from driving haircuts down (sometimes to zero), which reportedly has been the case in recent years." (Group of 30, 2021). Regulation of margin is not a new concept. Similar minimum margin requirements for Treasury repo were considered and then abandoned after the 1958 Treasury market stress (see Kahn and Nguyen (2022)). Kupiec (1997) also reviews discussions of regulating of margin requirements for equities under Regulation T in the wake of the 1987 stock market crash. Return to text

3. See Banegas and Monin (2023) for a discussion of haircuts and leverage for U.S. hedge funds. Return to text

4. In contrast, in derivatives markets substantial fundamental differences exist between contracts that are centrally cleared and those that are not, causing non-centrally cleared derivatives contracts to be generally riskier and less liquid than centrally cleared ones. Return to text

5. As the custodian, BNY ensures that margin that has been bilaterally negotiated is posted from cash borrowers to cash lenders but does not set margins. Return to text

6. For further background on NCCBR see Hempel et al. (2023b). Return to text

7. Market participants have provided various explanations for the prevalence of zero haircuts, including offsetting repo or derivatives trades, as discussed below, and competitive pressures pushing haircuts down. Return to text

8. For instance, as covered by Copeland and Kahn (2024), in the sponsored repo market (an important venue for customers) the direct clearing member in the trade will be margined by the CCP but any customer margin is determined bilaterally between the direct clearing member and customer. Return to text

9. The December 2023 Senior Credit Officer Opinion Survey on Dealer Financing Terms (PDF) found that only one-fifth of dealers surveyed generally collected margin from customers in FICC sponsored repo, while market participants have noted that hedge funds often receive zero haircuts in this segment. Return to text

10. See Brunnermeier and Pedersen (2009). Return to text

11. See Basel Committee on Banking Supervision Board (2020). These standards in turn reflect part of the U.S. implementation of the Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures, see Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems and Technical Committee of the International Organization of Securities Commissions (2012). Return to text

12. See 17 CFR 240.17ad-22(e)(6). Return to text

13. Infante (2019) considers optimal haircuts in a similar setting with strategic default and finds that haircuts can be negative when customers are sourcing specific securities from dealers. Return to text

14. Ideally, these percentiles would also take into account transaction costs associated with selling or buying the security, and some adjustment might be made to account for the correlation between default and returns on the security. Return to text

15. See Paddrik et al. (2021) and Hempel et al. (2023a) for a breakdown of lenders and borrowers in the tri-party market. Return to text

16. See Ross (2022). Additionally, as a practical matter, the collateral is held in custody at the Bank of New York and is not at risk of not being returned. Return to text

17. This is consistent with the standard in Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2020) that "offsetting risks… can and should be reliably quantified for the purposes of calculating initial margin requirements." Return to text

18. This has been recognized for some time in the context of derivatives, see Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2020) and Cox et al. (2016). Return to text

19. In a cleared context, the importance of cross-margining for these types of positions was recently noted by the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee. See Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee, "Inter-Agency Working Group's efforts on Treasury Market Resilience (PDF)," October 29, 2024, page 31. Return to text

20. For more details, see Barth and Kahn (2021). Similar arguments for cross-margining exposures in the basis trade are made by Younger (2021). Return to text

21. Specifically, the dealer would be the futures commission merchant to the trader on the futures contract. Return to text

22. As outlined in Barth and Kahn (2021) margin and rollover risk are the principal risks of the trade. Return to text

Kahn, R. Jay, and Matthew McCormick (2025). "Proportionate margining for repo transactions," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, February 14, 2025, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3722.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.