FEDS Notes

October 07, 2020

The Corporate Bond Market Crises and the Government Response

Steven Sharpe and Alex Zhou†

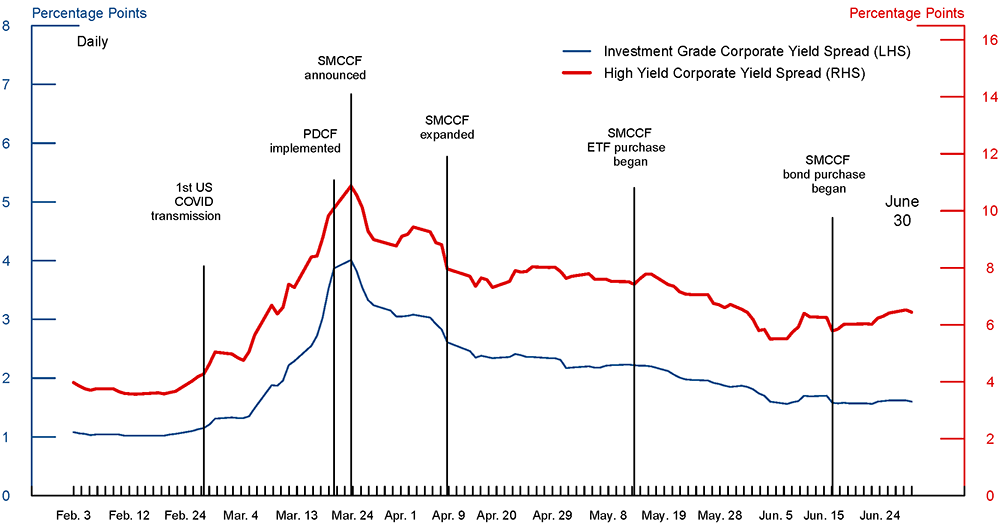

The Covid-19 pandemic led to acute stress in the global economy and, as a consequence, many parts of the global financial system. In the U.S., when concerns over the coronavirus escalated in March, many financial markets were hit by extraordinary selling pressure. Bond mutual funds suffered net outflows exceeding $250 billion in March, or about five percent of their assets under management. Even funds specializing in short-term investment-grade bonds experienced outflows in March totaling eight percent of assets, dwarfing the selling pressure they saw during the global financial crises. Underlying these developments, liquidity provision by security dealers deteriorated, as some dealers reportedly reached their balance sheet capacity and hence were unable to absorb more sales. Together with the surging demand for liquidity, the pullback by dealers led to severely constrained liquidity conditions in the corporate bond markets. Amid the broad risk-off sentiment, corporate bond yield spreads widened dramatically (Figure 1), while issuance of new bonds came to a halt.

This figure shows movements in ICE BofA option−adjusted yield spreads for US investment−grade (left) and high−yield (right) bonds around the onset of Covid−19 crisis.

Data source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

The Covid crisis spurred a variety of policy actions involving fiscal stimulus (including the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act) and monetary policy responses, including the creation of numerous liquidity and credit facilities. Among these was the unprecedented creation of facilities to purchase corporate bonds, funded by the Federal Reserve and backed with equity invested by the Treasury Department. In the study "Anatomy of a Liquidity Crisis: Corporate Bonds in the Covid-19 Crisis", O'Hara and Zhou (2020) analyze the impact of dealer and customer behavior on corporate bond market liquidity, as well as the effectiveness of Federal Reserve credit and liquidity facilities targeting the corporate bond markets. In this note, we review the events described in the study, highlight some key findings, and provide some additional analysis on the facilities' effects.

The Bond Market Liquidity Crisis and the Government Responses

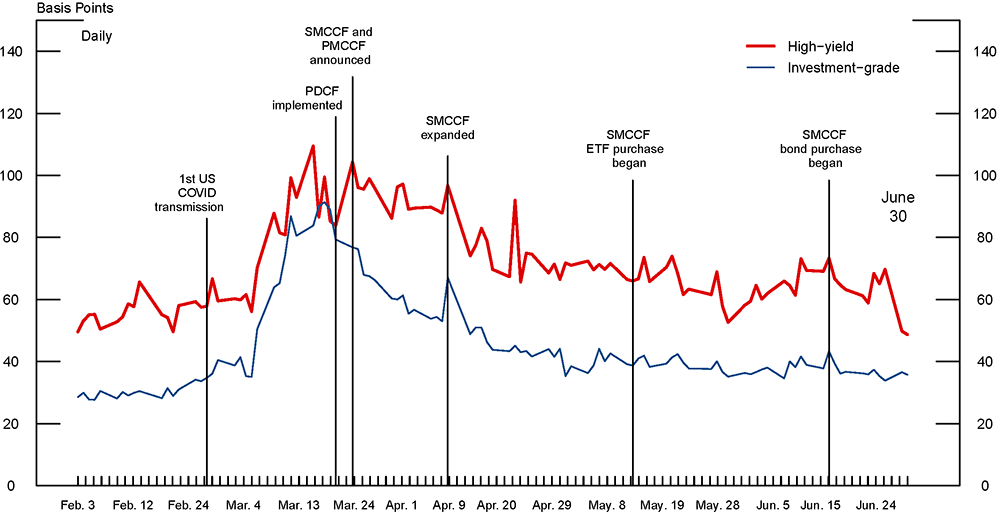

Liquidity conditions in corporate bond markets deteriorated precipitously in early March. As shown in Figure 2, bond transaction costs soared over a span of less than two weeks. Perhaps most dramatic was the near tripling in the average cost for investment-grade bond transactions, from around 30 basis points (per dollar of principal traded) in February to nearly 90 basis points in mid-March, levels not seen since the financial crises that precipitated the Great Recession.1

Data source: TRACE data provided by FINRA. See O'Hara and Zhou (2020) for details on estimating transaction costs.

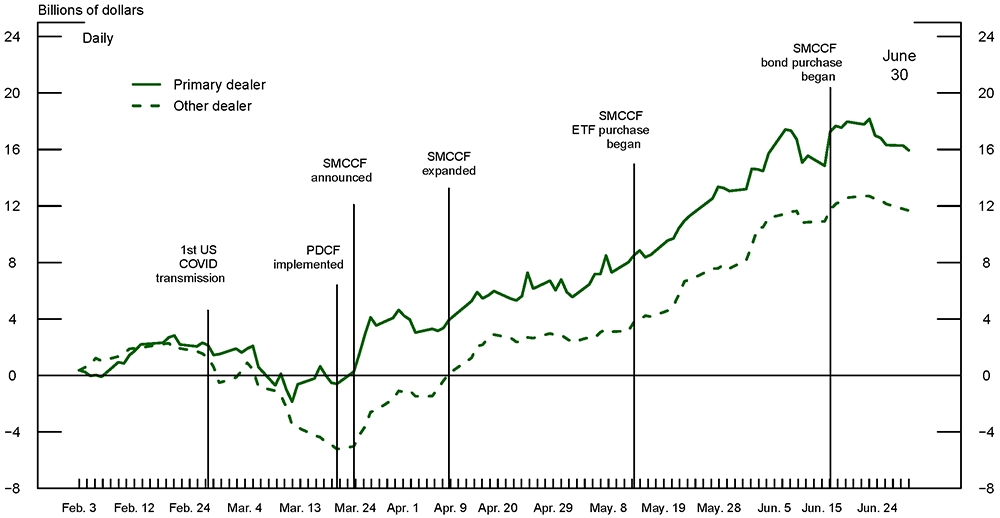

Underlying the spike in transactions costs, during the two weeks leading up to Fed interventions, dealers, particularly non-primary dealers, shifted from buying to selling, causing their inventories to plummet. As shown in Figure 3, cumulative inventory changes at primary dealers since the beginning of February were relatively stable before dipping into negative territory in early March. But net selling by non-primary dealers accounted for most of the overall decline in dealer inventories. As dealers stepped aside, trading in large quantities became particularly challenging. Transaction costs for block trades in investment-grade bonds, which were only 24 bps in February, had jumped to over 150 bps by March 23.

Figure 3. Cumulative inventory changes since the beginning of February for primary and other dealers

Data source: TRACE data provided by FINRA. See O'Hara and Zhou (2020) for details on constructing cumulative dealer inventory changes.

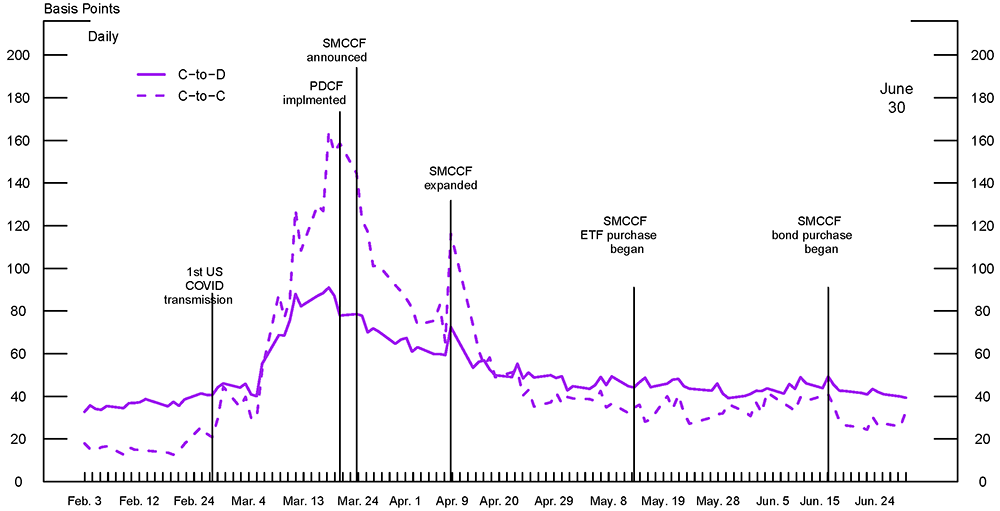

Growth in electronic trading over the past couple of years has brought additional sources of liquidity to the corporate bond market by facilitating customers, including asset managers, insurance firms, and hedge funds, trading directly with each other. Such liquidity provision by customers can be particularly valuable when the dealer community is unable or unwilling to make markets. However, as electronic customer-to-customer (C-to-C) trading increased amidst the dealer pullback in March, such trades occurred at prohibitively high costs. As shown in Figure 4, in February transaction costs for C-to-C trades were lower than costs for customer-to-dealer (C-to-D) trades; however, by mid-March, the trading cost differential had reversed and widened sharply, with C-to-C trade costs reaching 165 bps, more than double the cost for C-to-D trades.

Figure 4. Transaction costs for customer−to−dealer (C−to−D) and customer−to−customer (C−to−C) trades

Data source: TRACE data provided by FINRA. See O'Hara and Zhou (2020) for details on estimating transaction costs for C−to−D and C−to−C trades.

In mid-March, the Federal Reserve took several actions to improve market functioning. A number of liquidity and credit facilities were created to either enhance the supply of liquidity or to directly increase the demand for debt securities. The facilities that had the most direct impact on secondary market liquidity in the corporate bond markets were the Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF), and the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF).

The Fed announced the creation of the PDCF on Tuesday, March 17, with credit extended to primary dealers starting on March 20. The PDCF offers overnight and term funding with maturities up to 90 days to primary dealers at the discount rate offered by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. All credit extended by the PDCF can be collateralized by a broad range of investment-grade debt securities, including investment-grade corporate and municipal bonds and commercial paper. In contrast with the PDCF established in 2008 in response to the subprime mortgage crisis and collapse of Bear Stearns, which offered only overnight loans to primary dealers, the newly launched PDCF provided 90-day term funding, meant to be helpful for funding illiquid corporate bond inventories. But any improvement in funding conditions brought by the PDCF alone might not have been sufficient to induce increased liquidity provision. If excessive selling pressure were to persist, dealers might be reluctant to take bonds into inventories given potential future challenges to turning them over.

On Monday, March 23, for the first time in its history, the Federal Reserve, together with the Department of the Treasury, created a facility to directly purchase investment-grade corporate bonds of U.S. companies in the secondary markets. Under the SMCCF, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York would provide recourse loans to a special purpose vehicle (SPV) that would purchase eligible investment-grade corporate bonds at fair market value. Eligibility was limited to bonds with a remaining maturity of five years or less. The Department of Treasury would provide a $10 billion equity investment, and the SMCCF could leverage Treasury's equity at up to a 10 to 1 ratio.

By promising a liquidity backstop for corporate bonds, the announcement of the SMCCF not only reduced investors' concerns, but provided some assurance to dealers regarding their ability to turn over inventories, thereby increasing their willingness to intermediate bond trading. Finally, the Federal Reserve simultaneously announced the creation of the Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility (PMCCF), structured similarly to the SMCCF but with the charge of purchasing newly issued bonds directly from corporate issuers. By reducing the risk that issuers would later be unable to rollover maturing debt, the PMCCF reduced a major source of future negative tail risks, which almost surely bolstered market sentiment as well as dealers' willingness to provide liquidity.

The Impact of Fed Facilities on Bond Liquidity

The creation of these Federal Reserve liquidity and credit facilities had a swift and significant impact on corporate bond liquidity. Dealers started to increase their inventories following the implementation of the PDCF on March 20 and the announcement of the SMCCF on March 23. Initially, inventory accumulation by primary dealers was almost entirely in investment-grade bonds, suggesting that the credit available under the PDCF had eased their funding conditions. Meanwhile, customer-to-customer electronic trading activity declined as dealers intermediated more trades.

Bond transaction costs turned lower immediately following the implementation of the PDCF on Friday March 20, and declined further following the announcement of the PMCCF and SMCCF the following Monday (Figure 2). Most of the initial declines in transaction costs occurred in the investment-grade sector, consistent with high-yield bonds not being eligible for either the PDCF or the SMCCF according to their initial terms. The days following the SMCCF announcement also saw a rebound in corporate bond prices, resulting in a substantial easing in the yield spreads on both investment-grade and high-yield bonds (Figure 1); as a result, public issuance of new corporate bonds soared.

The scale and scope of both the SMCCF and PMCCF were increased on April 9. Treasury's planned equity investment in the SMCCF was raised from $10 billion to $25 billion. At the same time, eligible assets for purchase for the SMCCF were expanded to include high-yield bonds rated at least BB-/Ba3 that had been downgraded from investment-grade after March 22 ("recent fallen angels") as well as ETFs whose primary investment objective is exposure to high-yield U.S. corporate bonds.2 The increase in capitalization and purchase capacity amounted to a very sizable boost in government backing for the program; whereas the expansion in asset eligibility was quantitatively less substantial, it appeared to be taken as a signal of deeper commitment.3 Indeed, following the announced expansion of the SMCCF, transaction costs in high-yield bonds also began to drift downwards, while those in investment-grade bonds continued to decrease.4 By the end of April, average transaction costs appeared to stabilize, albeit at still somewhat elevated levels.

The design of the SMCCF also facilitates an analysis to differentiate its impact from other government actions taken around the SMCCF announcement. Because the SMCCF, in its initial design, was only authorized to accept investment-grade bonds with remaining maturities of 5 years or less, any liquidity improvement induced directly by the facility should have been stronger among bonds maturing in less than 5 years. Indeed, the study finds that, compared to investment-grade bonds with remaining maturities just above the 5-year boundary, those with remaining maturities just below that boundary exhibited an additional 21 basis points decline in transaction costs during the week following the announcement of the SMCCF. Nonetheless, subsequent analysis indicates that, in fairly short order, the improvement in transactions costs diffused throughout the market to non-eligible bonds. In particular, the extra decline in transaction costs for bonds maturing in just under 5 years shrank to 15 basis points in the second week after the SMCCF announcement and to only (a statistically insignificant) 9 basis points in the week after that.

Notably, these liquidity benefits, and the concomitant easing in corporate bond yield spreads, took place before a single bond was actually purchased by the facility. Indeed, as shown in Figures 2 and 4, the commencement of actual purchases by the SMCCF, which only began on May 12 for bond ETFs, and on June 16 for individual bonds, had relatively little discernible incremental impact on transactions costs as gauged by the O'Hara-Zhou measure. Moreover, a statistical test of a differential benefit for eligible bonds (again, investment-grade bonds just inside the 5-year maturity eligibility boundary) by eligible sellers (i.e., primary dealers) finds no discernible difference in liquidity changes surrounding the start of individual bond purchases.

Going forward, what happens?

As of July 31st, the SMCCF so far had employed only a very small fraction of its capacity, just over $12 billion of the allotted $250 billion. Moreover, data from the weekly H.4.1 statistical release indicate that SMCCF purchases in August had slowed to a pace of only around $100 million per week, well under a tenth of the pace when the facility first opened. At the same time, the PMCCF has yet to purchase new bonds from a single issuer, while the vigorous pace of new bond issuance to private investors in the second-quarter far outran previous records. While such a broad-based and speedy rebound in the multi-trillion corporate bond market might seem improbable given the relatively modest resources actually deployed, ideally, this is how a backstop is supposed to work. It restores market functioning by halting investor runs that can result in a self-fulfilling equilibrium involving serial defaults, widespread bankruptcies, as well as the collateral damage to defaulting firms' employees and suppliers. Such an equilibrium almost surely would have deepened the economic contraction, causing more extensive damage to employment and economic output.

In essence, the Federal Reserve took on a new role of "market maker of last resort", as advocated by Buiter and Sibert (2007). Going forward, however, it is important to consider that this action potentially could have some longer-term effects on the overall market. In particular, to the extent that this episode creates an expectation that such interventions could be contemplated in the future, it may encourage firms to employ bond financing to obtain greater leverage. Weighing somewhat in the other direction, the experience might also be seen as pointing to a new advantage of maintaining an investment-grade rating. Finally, through its acceptance of corporate bonds as collateral for funding as well as its outright purchases, the Federal Reserve will inevitably influence the assessment and pricing of credit risks and instruments (Small and Clouse (2005)). Whether and how such Fed actions ultimately affect the longer-term allocation of credit in the economy remains to be seen.

References

Buiter, Willem, and Anne Sibert (2007). "The Central Bank as the Market Maker of last Resort: From Lender of last resort to market makers of last resort," Vox CEPR Policy Portal, August 13, 2007.

Hendershott, Terry, and Anand Madhavan (2015). "Click or call? Auction versus search in the Over-the-Counter market," Journal of Finance 70, 419–447.

O'Hara, Maureen, and Alex Xing Zhou (2020). "Anatomy of a Liquidity Crisis: Corporate Bonds in the Covid-19 Crisis," Journal of Financial Economics, forthcoming.

Small, David, and James Clouse (2005). "The Scope of Monetary Policy Actions Authorized under the Federal Reserve Act," Topics in Macroeconomics 5(1), 1–45.

* We thank FINRA for providing the data used in this study. Frank Ye provided excellent research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors or its staff. All errors are our own.

†. Both authors are at the Federal Reserve Board. E-mails: [email protected], and [email protected]. Return to text

1. A 90 basis point cost for transacting would indicate that the initiator of a trade would need to spend $90 per $10,000 of bonds traded. For bonds that pay a 4 percent interest rate, for example, this would thus amount to losing nearly a quarter of the interest earned in the first year. Transactions costs are estimated following Hendershott and Madhavan (2015). Return to text

2. The SMCCF will leverage Treasury's equity at 7 to 1 when acquiring high-yield corporate bonds. Return to text

3. The preponderance of ETF purchases were still slated to be of bond ETFs focused on investment-grade debt. Similarly, bonds of recent fallen angels were expected to constitute only a small fraction of individual bond purchases. Nonetheless, removing the hard eligibility boundary between investment-grade and high-yield debt was seen as a way to soften potential "cliff effects", whereby the creation of a facility prohibited from purchasing any below-investment-grade bonds conceivably could have made the high-yield bond sector even less attractive to private investors than in the absence of the SMCCF. Return to text

4. Although transaction costs spiked on April 9 after S&P downgraded a total of 143 bonds, that move was more than retraced in the days that followed and transactions costs continued to trend back down. Return to text

Sharpe, Steven A., and Alex X. Zhou (2020). "The Corporate Bond Market Crises and the Government Response," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, October 07, 2020, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.2769.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.