FEDS Notes

March 31, 2025

The Effect of Export Market Access on Labor Market Power: Firm-level Evidence from Vietnam

Sydney Eck, Trang Hoang, Devashish Mitra, and Hoang Pham

Introduction

Many developing and developed countries have experienced a declining labor share of national output in recent decades (Karabarbounis and Neiman, 2014). Some blame the decline on globalization, although it is surprisingly unclear whether and how globalization is a key contributing factor (Grossman and Oberfield, 2022). This note contributes to this debate by studying how an export market expansion affects micro-level domestic labor markets. Specifically, our work offers insights on the share of a worker's wage in the additional firm revenue their employment creates via a unique mechanism: labor-market power.

To shed light on this question, we examine the effect of the 2001 U.S.-Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement (BTA) on the Vietnamese manufacturing sector, using firm-level data from 2000 to 2010. The BTA is a far-reaching free trade agreement that protects intellectual property rights, facilitates business transparency, and—most notably—reduces tariffs between the U.S. and Vietnam. We first estimate a measure of firm-level labor market power, i.e., the wedge between wages and the marginal revenue products of labor (MRPL), based on the method developed by Gandhi, Navarro, and Rivers (2020, hereafter GNR). Then, we explore how this measure of labor market distortion responds to the BTA.

Our findings show that firms in industries more exposed to the U.S. tariff reductions see a faster decline in their labor market distortion. This decrease in distortion is due to an increase in firm entry following the BTA, which increases competition in the local labor market. We further exploit information on the gender composition to estimate the MRPL-wage wedges separately for men and women. We find that the median distortion is higher for women relative to men, and the decline in distortion for women is the driver of the overall reduction in labor market distortion attributable to the BTA.

Background information

The BTA took about five years to negotiate and went into effect in December 2001. Following the BTA, the U.S. granted Normal Trade Relations (NTR) / Most Favored Nation (MFN) status to Vietnam and allowed Vietnam's exports immediate access to the U.S. market. As a result, Vietnam was moved from "Column 2" to "Column 1" (MFN) of the U.S. tariff schedule. The "Column 2" tariffs are those assigned to nonmarket economies under the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930. The MFN tariffs are those offered to all WTO members by the U.S. and were determined through a multilateral bargaining process with other countries long before 2001. Thus, although the BTA involved a lengthy negotiation process on both sides, the magnitude of changes to U.S. tariffs on imports of Vietnamese products were largely predetermined and not influenced by either the U.S. or Vietnam's bargaining positions.

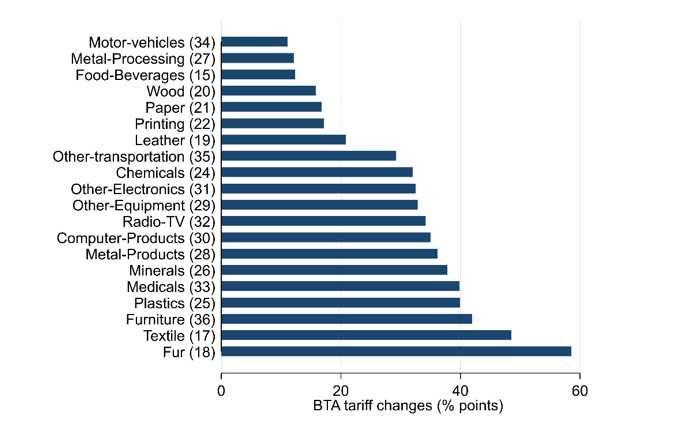

The BTA tariff reductions are large in magnitude. Following the BTA, the ad valorem U.S. tariffs on Vietnam's products went down from an average of 23.4 percent to 2.5 percent at the 2-digit industry level. The tariff decrease is the largest for the manufacturing sector, which went from an average of 33.8% to 3.6%. BTA tariff changes across 2-digit manufacturing industries are shown in Figure 1. Tariff reductions are much more modest for agriculture and other primary sectors.

Notes: The figure illustrates the tariff reductions across 2-digit manufacturing industries following the U.S.-Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement (BTA) in December 2001.

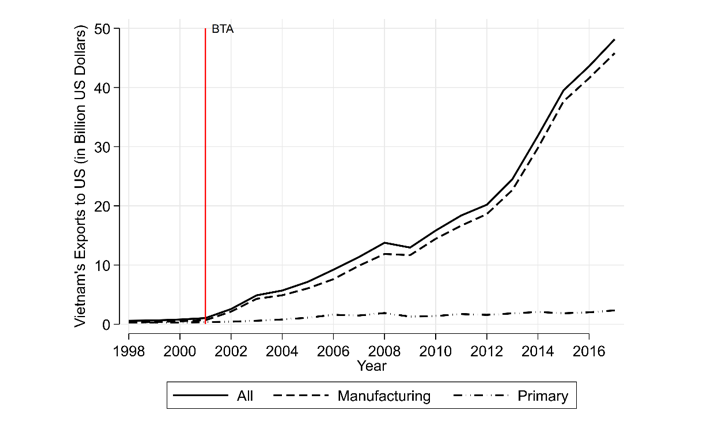

The BTA was followed by immediate and extensive growth in Vietnam's manufacturing exports to the U.S. Figure 2 illustrates Vietnam's export value to the U.S. from 1998 to 2016. In 2001, before the BTA, exports to the U.S. were about 1.04 billion U.S. dollars, representing only 6.5% of total exports (and 3.2% of GDP). In 2002, immediately after the BTA came into force, exports to the U.S. grew to 2.6 billion U.S. dollars, a two-and-a-half fold increase in one year. By 2016, Vietnam exported 43.6 billion U.S. dollars' worth of its products to the U.S., which represented 20% of total exports (and nearly 21% of GDP). Figure 2 shows that manufacturing represents the bulk of the increase in Vietnam's exports to the U.S. The share of the U.S as a destination of Vietnam's manufacturing exports increased from an average of 40% before the BTA to around 87% in 2006 and 92% in 2016, respectively.

Data Descriptions

We use the Vietnam Enterprise Survey (VES) data for 2000-2010, which are collected annually by Vietnam's General Statistics Office (GSO).1 The VES contains a wide range of information, including firm identification (ID), ownership types, industry classification, geographical information, sales, employment, total labor compensation, material expenditures, and capital stock. An important advantage of the VES is that it contains consistent information about labor composition, particularly gender composition, which we exploit to estimate MRPL separately for men and women. Our BTA tariff data are obtained from McCaig and Pavcnik (2018) and McCaig, Pavcnik, and Wong (2022).

Measuring Labor Market Distortions

Labor market distortion, denoted by χ, is defined as the wedge between MRPL and wages. Let R and L denote revenue and number of employees, respectively and r and l are log of R and L. With simple derivations, we can rewrite χ as follows:

χ= MRPLwage= (∂r∂lLR)wage= (∂r∂l)(wage×LR)

where the numerator is the revenue elasticity of labor, and the denominator is the labor share of total revenue. We can compute the labor share of revenue directly using data on revenue and total labor compensation. To estimate the revenue elasticity of labor, we employ the first-order condition method introduced by Gandhi, Navarro, and Rivers (2020).

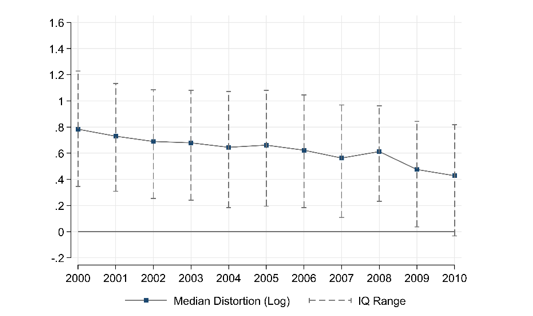

We find that the median labor market distortion during our sample period is 1.7, implying that a worker got paid 59% of the marginal revenue that he (she) brought to the median firm. We see distortions across all industries, suggesting that there was pervasive market distortion in the Vietnamese manufacturing sector during the 2000-2010 period. That said, the log of median distortion declined over time, as shown by the figure below.

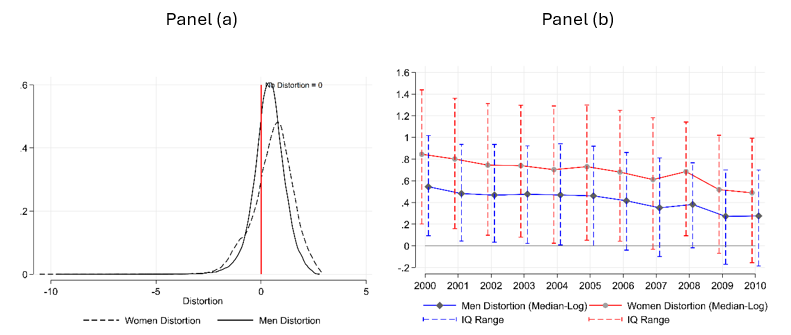

Next, we estimate the distortions separately for men and women. To so do, we estimate a modified revenue function that treats male and female workers as two different human capital inputs. The identification and estimation of the modified revenue function follows from the baseline model as in the GNR method. Panel (a) of Figure 4 illustrates kernel densities of the log-measured labor market distortions for men and women. We find that women get paid 52% of their MRPL while men get paid 68% of their MRPL at the respective median firms. Nonetheless, we find that this gap in distortions across gender narrows significantly over time, as shown in Panel (b) of Figure 4. This trend implies that the labor market for women in manufacturing has become much more competitive, although the gap persists.

The Effects of BTA: Regression Analysis

A key objective of this note is to understand how the BTA tariff reductions affected the labor market distortions in Vietnam's manufacturing industries. We begin this section by estimating a baseline difference-in-difference (DID) model as follows:

logχijpt=θ×PostBT At×τBTA−gapj+ λi+ λpt+ ϵijpt (1)

The dependent variable is the log of measured labor market distortion for firm i in industry j at province p in year t. PostBT At is an indicator variable for post-BTA years and equals 1 if t≥2002 and 0 otherwise. τBTA−gapj is the difference between the MFN and "Column 2" tariff of industry j. λi and λpt are firm and province-year fixed effects. The coefficient of interest is θ. Intuitively, θ is identified by comparing the outcome variable's differential changes across firms within the same province-by-year cell. These firms differ only in their differential exposure to changes in BTA tariffs due to their industry affiliations.

Table 1 reports the results for the baseline DID regressions for equation (1) and also with other labor market variables as dependent variables (L, W, and MRPL). Column (1) shows that firms that operate in industries more exposed to the BTA tariff reductions see faster employment growth. Column (2) reveals that the BTA has a statistically significant impact on the overall relative wage growth for these firms in our sample period, even though the magnitude of the coefficient is much smaller. From column 3, we find that firms more exposed to the BTA see some pressure in MRPL (slower relative growth), although this estimate is not statistically significant. Combining MRPL with the wage response, the BTA leads to a relative reduction in labor market distortion, as shown in column (4). The average BTA tariff reduction at the 2-digit industry level is 30 log points. This implies that the labor market distortion has decreased by 30× 0.112≈3.4 percent due to the BTA.

Table 1: Impact of BTA on firm-level outcomes

| Dependent Variables | (1) log(L) |

(2) log(W) |

(3) log(MRPL) |

(4) log(X) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| τBTA−gapj × Post BTA (2-digit) | -0.201*** | -0.074* | 0.056 | 0.112** |

| (0.056) | (0.039) | (0.047) | (0.045) | |

| Observations | 128,406 | 128,406 | 118,437 | 118,437 |

| R-squared | 0.911 | 0.725 | 0.711 | 0.609 |

| Firm FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Province-Year FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Clustered Two-way | ||||

| Firm | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Industry-by-year | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Notes: The table reports the results of regression equation (1) with four dependent variables: (1) log of employment, (2) log wage, (3) log of MRPL, and (4) log of measured distortion. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered two-way at the firm and industry-by-year levels (*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1).

Using our extended measurement results from the previous section, we next estimate the BTA effect separately for firm-level outcomes regarding men and women in manufacturing. Columns (7)-(8) in Table 2 demonstrate that the effect of the BTA on labor market distortions is significant and much larger for women, suggesting that the overall reduction in labor market distortion is mainly driven by the decreased labor market distortion for women in manufacturing. Using the simple calculation based on the estimated elasticity again, the distortion for women has decreased by 30× 0.405≈12.2 percent due to the BTA. The overall decrease in distortion of 3.4 percent computed from the baseline regression is thus the net effect of two factors: (1) the increase in the share of women in manufacturing following the BTA, which increases the average distortion (because women's labor markets are characterized by higher distortions), and (2) the endogenous decrease in the distortion for women in response to the BTA.

Table 2: Impact of the BTA on firm-level outcomes: Manufacturing men versus women

| Dependent Variables | Employment | Wage | MRPL | Distortion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) log(U + 1) |

(2) log(V + 1) |

(3) log(WU) |

(4) log(WV) |

(5) log(MRPLU) |

(6) log(MRPLV) |

(7) log(XU) |

(8) Log(XV) |

|

| τBTA−gapj × Post BTA (2-digit) | -0.106*** | -0.249*** | 0.058 | -0.291*** | -0.006 | 0.126** | -0.077 | 0.405*** |

| (0.051) | (0.064) | (0.046) | (0.053) | (0.049) | (0.050) | (0.055) | (0.064) | |

| Observations | 125,577 | 125,577 | 125,558 | 125,574 | 121,348 | 113,978 | 121,329 | 113,975 |

| R-squared | 0.889 | 0.927 | 0.718 | 0.731 | 0.759 | 0.784 | 0.637 | 0.731 |

| Firm FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Province-Year FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Clustered Two-way | ||||||||

| Firm | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Industry-by-year | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Notes: The table reports the results of regression equation (1) with separate dependent variables for men in manufacturing (U) and women in manufacturing (V). Standard errors in parentheses are clustered two-way at the firm and industry-by-year levels (*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1).

A data-consistent theory

To explain our empirical results, we set up a simple equilibrium model of export market access with firm entry and oligopsony in the labor market, closely related to Pham (2023). We start with a baseline model where workers are treated as a single human capital input and then extend it to allow for two types of workers: men and women. We assume that a continuum of symmetric firms populates a domestic tradable goods sector, and firms are price takers in the goods market. We also assume that the home country is a small open economy, so home firms take world prices as given. On the other hand, firms are allocated to a continuum of symmetric local labor markets, and within each local market, the number of firms is finite. This setup allows us to focus on modeling the equilibrium within each local market while the aggregate economy's outcomes can be easily inferred from the local market outcomes.

Three key results emerge from the model:

- The firm-level profit maximization implies that firm-level labor market distortion, i.e., the wedge between MRPL and wage, is a function of aggregate labor supply elasticity and the number of firms in the local market. In particular, labor market distortion is decreasing in both the labor supply elasticity and the number of firms in the local market.

- In equilibrium, the number of firms in the local market is decreasing in the level of tariffs imposed by foreign countries on domestic goods. The intuition is that, as tariffs in foreign markets decrease, domestic firms' profits increase, inducing more entry of domestic firms. Combined with (1), this result implies that a reduction in foreign tariffs will lower labor market distortions through a larger number of firms (and thus competition) in the labor market.

- The relative effect of the BTA on men's versus women's labor market distortion depends on their relative labor supply elasticities. If the aggregate labor supply is more elastic for men than for women, firms exercise less market power over men than women, but lower foreign tariffs will narrow the distortion gap between men and women, consistent with our empirical findings.

Conclusion

In this note, we study the impact of the expansion of export market access created by the U.S.-Vietnam BTA on competition among manufacturing firms in Vietnam's local labor markets. We measure firm-level labor market power (distortion) using Vietnamese data from 2000-2010 and find that labor-market distortion is substantial and pervasive: a worker gets paid only about 59% of their MRPL at the median firm. This result is in line with previous estimates for developing countries (e.g., Amodio and de Roux (2021) for Columbia, Pham (2023) for China, and most recently Amodio et al. (2024) for 82 low and middle-income countries). We find that the BTA permanently decreases the labor market distortion in manufacturing by 3.4%. In addition, when considering men and women separately, we find the distortion for women in manufacturing is substantially higher and that the BTA-associated decline in the overall labor market distortion is primarily driven by the decline in distortion for women, which decreased more than 12%. This result highlights that trade has a substantial impact on misallocation and gender inequality that takes effect through the labor market competition channel.

Several questions remain open for future research. First, we have an on-going working paper in which we propose a theoretical framework that can explain these empirical findings. Second, while we have carefully estimated the levels and changes of labor market distortions at the firm level, we have yet to quantify the resulting aggregate implications. Quantifying the aggregate welfare gains from our results is important for future work. Third, we plan to explore further the mechanisms through which trade affects labor market distortions and work for men and women (demand side versus supply side barriers), as well as the spillover effects to other formal or informal sectors outside of manufacturing. Dissecting such mechanisms and spillovers will have important implications for theory and trade policy formulation in developing countries.

References

Amodio, Francesco, and Nicolas de Roux. 2021. "Labor Market Power in Developing Countries: Evidence from Colombian Plants." IZA Discussion Paper No. 14390.

Gandhi, Amit, Salvador Navarro, and David A Rivers. 2020. "On the Identification of Gross Output Production Functions." Journal of Political Economy, 128(8): 2973–3016.

Grossman, Gene M, and Ezra Oberfield. 2022. "The Elusive Explanation for the Declining Labor Share."Annual Review of Economics, 14: 93–124.

Hoang, Trang, Devashish Mitra, and Hoang Pham. 2024. "The Effect of Export Market Access on Labor Market Power: Firm-level Evidence from Vietnam," International Finance Discussion Papers 1394. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Karabarbounis, Loukas, and Brent Neiman. 2014. "The Global Decline of the Labor Share." The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(1): 61–103.

McCaig, Brian, and Nina Pavcnik. 2018. "Export Markets and Labor Allocation in a Low-Income Country." American Economic Review, 108(7): 1899–1941.

McCaig, Brian, Nina Pavcnik, and Woan Foong Wong. 2022. "FDI Inflows and Domestic Firms: Adjustments to New Export Opportunities." National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 30729.

Pham, Hoang. 2023. "Trade reform, oligopsony, and labor market distortion: Theory and evidence." Journal of International Economics, 144, 103787, ISSN 0022-1996, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2023.103787.

1. Link to website: www.gso.gov.vn. Return to text

Eck, Sydney, Trang Hoang, Devashish Mitra, and Hoang Pham (2025). "The Effect of Export Market Access on Labor Market Power: Firm-level Evidence from Vietnam," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, March 31, 2025, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3743.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.