FEDS Notes

December 20, 2024

"The Only Way I Could Afford It": Who Uses BNPL and Why

Jeff Larrimore, Alicia Lloro, Zofsha Merchant, and Anna Tranfaglia

Introduction

Buy now, pay later (BNPL) is a fast-growing credit product that allows consumers to split payments over time. BNPL gained popularity as a new alternative credit product for online retail purchases over the past decade and has become available for in-person purchases as well as post-purchase credit card installment payment plans. As an indication of how ubiquitous BNPL has become in the retail marketplace, a June 2023 survey found that nearly two-thirds of consumers had been offered a BNPL product in the past year (Aidala et al., 2023). Since BNPL is so widely offered, yet still relatively new, understanding who is using it and why is important to help inform policymakers about the benefits and risks that BNPL users face.1

In this note, we complement the growing literature on BNPL by exploring who uses BNPL and why. We exploit the relatively large sample and scope of the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED) to examine BNPL use by the intersection of race/ethnicity and gender, as well as to explore how BNPL use relates to people's financial circumstances.

We find that Black and Hispanic women were particularly likely to use BNPL. Their higher usage rates may be due, at least in part, to a greater preference for specific product features of BNPL like a fixed number of payments. Black and Hispanic women were not more likely than White women to use BNPL out of financial necessity.

Additionally, we show that adults who report lower overall financial well-being and those who appear liquidity or credit constrained were not only among the most likely to use BNPL, but most of these consumers also indicated that they used BNPL because it was the only way they could afford to make the purchase. In contrast, those with higher financial well-being and more financial resources were less likely to use BNPL in the first place, and those who did, typically did so to spread out payments or to avoid interest charges.

These findings highlight that while BNPL provides credit to financially vulnerable consumers, these same consumers may be overextending themselves. This concern is consistent with previous research that has shown consumers spend more when BNPL is offered when checking out and that BNPL use leads to an increase in overdraft fees and credit card interest payments and fees (Berg et al., 2023; deHann et al., 2022). That said, many BNPL users on firm financial footing find it to be a convenient way to make their purchase and spread out their payments.

Data

Our research uses the 2021 through 2023 Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED) (Federal Reserve Board, 2024b).2 The SHED is a nationally representative survey of over 11,000 U.S. adults conducted by the Federal Reserve Board each fall.3 The survey questions cover a range of topics including overall financial well-being, ability to handle emergency expenses, and credit use.

To provide further insight into why people use BNPL, for the 2023 SHED we merge credit information from Experian to the roughly 65 percent of respondents who agreed to have their survey responses anonymously matched with their credit history. The resulting credit-merge sample includes roughly 6,500 observations containing each consenting respondent's answers to the SHED, along with a snapshot of their credit history from September 2023.

The full SHED sample and the credit-merge sample look similar across demographic and financial characteristics, though we expect some differences because about 10 percent of the population does not have credit record.4 That said, the mean and median credit scores in the credit-merge sample (about 740 and 780, respectively) are higher than those observed among all the records in the credit bureau data (703 and 715). One reason for this difference may be that credit-merge sample represents actual people, whereas the full set of credit bureau records includes record fragments that typically have low corresponding credit scores. Another is that the SHED sample only includes non-institutionalized adults currently residing in the United States, whereas the credit bureau records include institutionalized individuals and individuals living abroad who have a credit history.

Buy Now Pay Later Usage

Before exploring the reasons people use BNPL, we first document overall usage rates, as well as how BNPL varies by demographic and financial characteristics. As of fall 2023, 14 percent of adults had used BNPL in the prior 12 months, up from 12 percent in 2022 and 10 percent in 2021.5,6

Similar to prior studies, we find that adults under age 60, adults without a bachelor's degree, Black and Hispanic adults, and women were more likely to use BNPL (Akana, 2022; CFPB, 2022; Doubinko & Akana, 2023; Shulpe et. al., 2023; Aidala et al., 2023).7 Additionally, these demographic patterns in BNPL use have remained consistent over the prior three years (see Federal Reserve Board 2022, 2023, 2024a for more detail).8

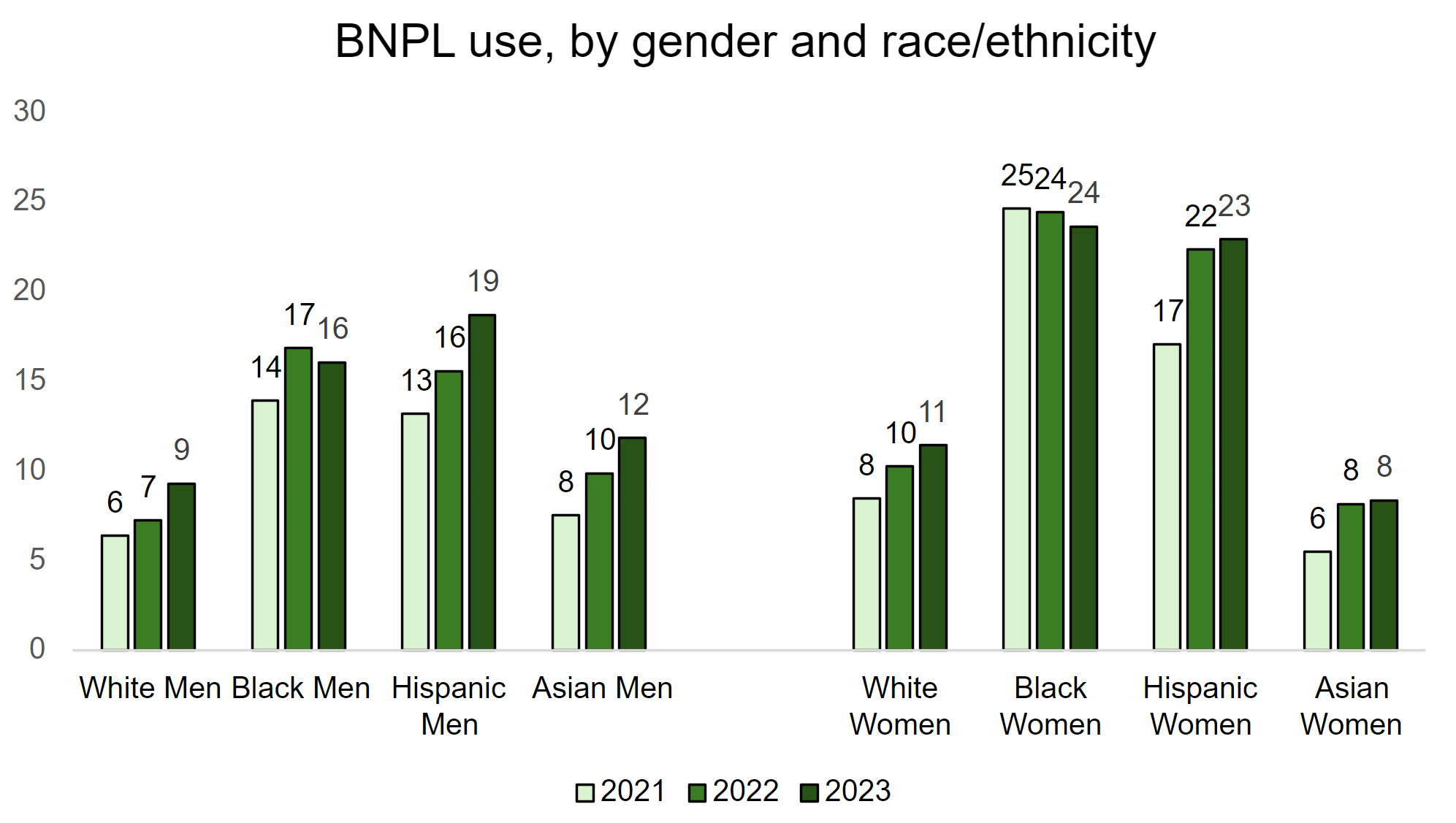

One advantage of the SHED over the surveys used in prior studies is its relatively large sample, allowing us to explore BNPL use among finer demographic groups. Looking at the intersection of race/ethnicity and gender, we find that Black and Hispanic women were particularly likely to use BNPL (figure 1). In 2023, about one-fourth of Black and Hispanic women used BNPL, more than double the rates of use among White women (11 percent) and Asian women (8 percent). Controlling for other factors like age, income, and credit score can explain about half of these higher use rates among Black women, yet only about one-fourth among Hispanic women. BNPL use among Black and Hispanic women was also higher compared with Black and Hispanic men. Controlling for other factors accounted for little of this gender gap.

Note: Key identifies bars in order from left to right.

Source: Authors' calculations using the 2021, 2022, and 2023 Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking.

We next turn to the relationship between people's financial situation and BNPL use. We find that those struggling financially and those with fewer financial resources were more likely to use BNPL – perhaps reflecting liquidity or credit constraints. Individuals who reported "just getting by" or "finding it difficult to get by" were nearly twice as likely to have used BNPL in the prior year as those "doing okay" or "living comfortably" (table 1). To gain some insight into whether BNPL users were already facing financial challenges before using BNPL, we turn to the subset of respondents who took both the 2022 and 2023 SHED. We find that those who used BNPL in 2023, but not in 2022, were already more likely to report "just getting by" or "finding it difficult to get by" as of the 2022 survey, before we first see them use BNPL.9

Table 1. BNPL use, by financial well-being and emergency savings

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doing OK or living comfortably | |||

| No | 17 | 20 | 21 |

| Yes | 8 | 9 | 11 |

| Largest emergency expense handled right now using only savings | |||

| Under $500 | - | 20 | 22 |

| $500 to $999 | - | 13 | 17 |

| $1000 to $1,999 | - | 12 | 14 |

| $2,000 or more | - | 6 | 7 |

| Family Income | |||

| Less than $25,000 | 12 | 14 | 14 |

| $25,000-$49,999 | 14 | 14 | 18 |

| $50,000-$99,999 | 11 | 14 | 15 |

| $100,000 or more | 7 | 8 | 10 |

Note: The question asking the largest emergency expense people could handle right now using savings was not asked in 2021.

Source: Authors' calculations using the 2021, 2022, and 2023 Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking.

Adults with smaller amounts of emergency savings and those with low- and middle-income were also more likely to use BNPL (table 1). For example, among adults who said the largest emergency expense they could handle using only savings was less than $500, about 2 in 10 (22 percent in 2023) used BNPL (table 1).

Results from both the full SHED sample and the credit-merge sample suggest that those who are credit constrained are among the most likely to use BNPL. Starting with the full SHED sample, we find that BNPL use is much higher among those who used credit alternative financial services (AFS), such as payday loans, and those who carried a balance on their credit card in the prior year (table 2). Consumers who had incurred overdraft fees were also more likely to be BNPL users, consistent with previous research (Di Maggio et al., 2022).

Table 2. BNPL Use, by financial characteristics

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Used an AFS Credit in the past 12 months | |||

| No | 9 | 11 | 12 |

| Yes | 33 | 40 | 40 |

| Credit card payment behavior in past 12 months | |||

| Never carried an unpaid balance | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Carried a balance once or some of the time | 15 | 16 | 19 |

| Carried a balance most or all of the time | 20 | 25 | 26 |

| Paid an overdraft fee on a bank account in the past 12 months | |||

| No | 8 | 9 | 11 |

| Yes | 30 | 35 | 35 |

Source: Authors' calculations using the 2021, 2022, and 2023 Survey of Household Economics and Decision making.

Among the credit-merge sample, those with lower credit scores were more likely to use BNPL.10 Nearly three in ten adults who had a credit score between 620 and 659 used BNPL, about three times higher than those with a credit score of at least 720. Moreover, the higher use of BNPL among those with lower credit scores holds across the age distribution (Table 3).

Table 3. BNPL use (by credit score and age)

| Credit Score | 18-29 | 30-44 | 45-59 | 60+ | All adults |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 620 | 31 | 28 | 36 | 20 | 30 |

| 620 - 659 | 31 | 31 | 27 | 24 | 29 |

| 660 - 719 | 24 | 28 | 25 | 20 | 24 |

| > 720 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 6 | 10 |

Source: Authors' calculations using the 2023 SHED credit-merge sample. Credit score is VantageScore 4.0.

Consumers with lower credit card limits also exhibited a higher demand for BNPL. More than 3 in 10 credit card owners with a total bankcard limit less than $5,000 used BNPL in the prior year. Those with a total credit card limit between $10,000 and $25,000 were half as likely to use BNPL (15 percent) as those with the limits under $5,000, possibly reflecting greater credit availability to make payments. An even lower 11 percent of adults with a total credit card limit over $50,000 used BNPL (table 4).

Table 4. BNPL Use, by credit card limit and utilization

| Characteristic | Used BNPL |

|---|---|

| Credit card limit | |

| $5000 or less | 31 |

| $5,000-$9,999 | 18 |

| $10,000-$24,999 | 15 |

| $25,000-$49,999 | 11 |

| $50,000 or more | 11 |

| Credit card utilization | |

| Less than 10% | 8 |

| 10-25% | 14 |

| 25-50% | 20 |

| 50-75% | 26 |

| 75-100% | 35 |

Source: Authors' calculations using the 2023 SHED credit-merge sample. Credit score is VantageScore 4.0.

Those using more of their total credit card limit are more likely to use BNPL. Thirty-five percent of those using more than 75% of their bankcard limit used BNPL in the prior year, compared to just 8 percent of adults who were using less than ten percent of the total limit (table 4).

BNPL users frequently sought other types of credit. BNPL users had an average of 0.93 credit card inquiries and 1.3 total inquiries in the prior year (table 5). This is approximately twice the number of inquiries that non-users had. In terms of credit repayment, BNPL users also had far more delinquent credit accounts than did non-users (table 5).

Table 5. Credit searching and repayment behavior

| BNPL users | Have not used BNPL in prior year | |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of bankcard revolving and charge inquiries made in the last 12 months | 0.93 | 0.41 |

| Total number of inquiries made in the last 12 months | 1.30 | 0.67 |

| Total number of trades presently 30 or more days delinquent or derogatory including collections | 1.82 | 0.54 |

| Total number of revolving trades ever 30 or more days delinquent or derogatory in the last 12 months | 0.52 | 0.13 |

Source: Authors' calculations using the 2023 SHED credit-merge sample. Credit score is VantageScore 4.0.

Taken together, these results suggest that BNPL users are heavy users of their existing credit and frequently are seeking additional credit products.

Self-Reported Reasons for using Buy Now Pay Later

There is no single reason why people use BNPL products. Prior studies from researchers at the Federal Reserve Banks of Philadelphia and New York have investigated why people use BNPL. Akana & Doubinko (2024) found that the most cited reason was convenience, while the least cited reason was that users thought they will not get approved for other types of credit. Aidala et al. (2024) asked respondents an open-ended question on why they used BNPL and found that financially stable users were more likely to mention avoiding interest, while financial fragile users mentioned convenience and ease of access.11

The SHED findings on why people use BNPL products are broadly consistent with this prior research. Nevertheless, the SHED provides additional insights into why people use BNPL, particularly for those who say they used BNPL because it was the only way they could afford their purchase. Moreover, the large sample and broad scope of SHED allow us to explore in more depth how the reasons for using BNPL differ according to people's demographic and financial characteristics.12

We classify the reasons for using BNPL broadly as follows: general preference or convenience, cost, payment timing, and necessity. Collectively, 88 percent of users cited at least one payment timing reason and 88 percent cited at least one reason related to convenience or payment preference (respondents could, and often did, select multiple reasons). A smaller 57 percent of users indicated that they were using BNPL for one of the reasons that related to necessity. This included the 55 percent of users who said that they used BNPL because it was the only way that they could afford it and 21 percent said it was the only accepted payment method that they had (table 6).

Table 6. Reasons for BNPL Use

| Reason | Share of BNPL users |

|---|---|

| Preference or convenience | 88 |

| Convenience | 82 |

| Did not want to use a credit card | 54 |

| Making payments over time | 88 |

| Wanted to spread out payments | 87 |

| Wanted a fixed number of payments | 46 |

| Avoiding interest charges | 59 |

| Necessity | 57 |

| Only way I could afford it | 55 |

| Only accepted payment method I had | 21 |

Source: Authors' calculations using the 2022 and 2023 Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking.

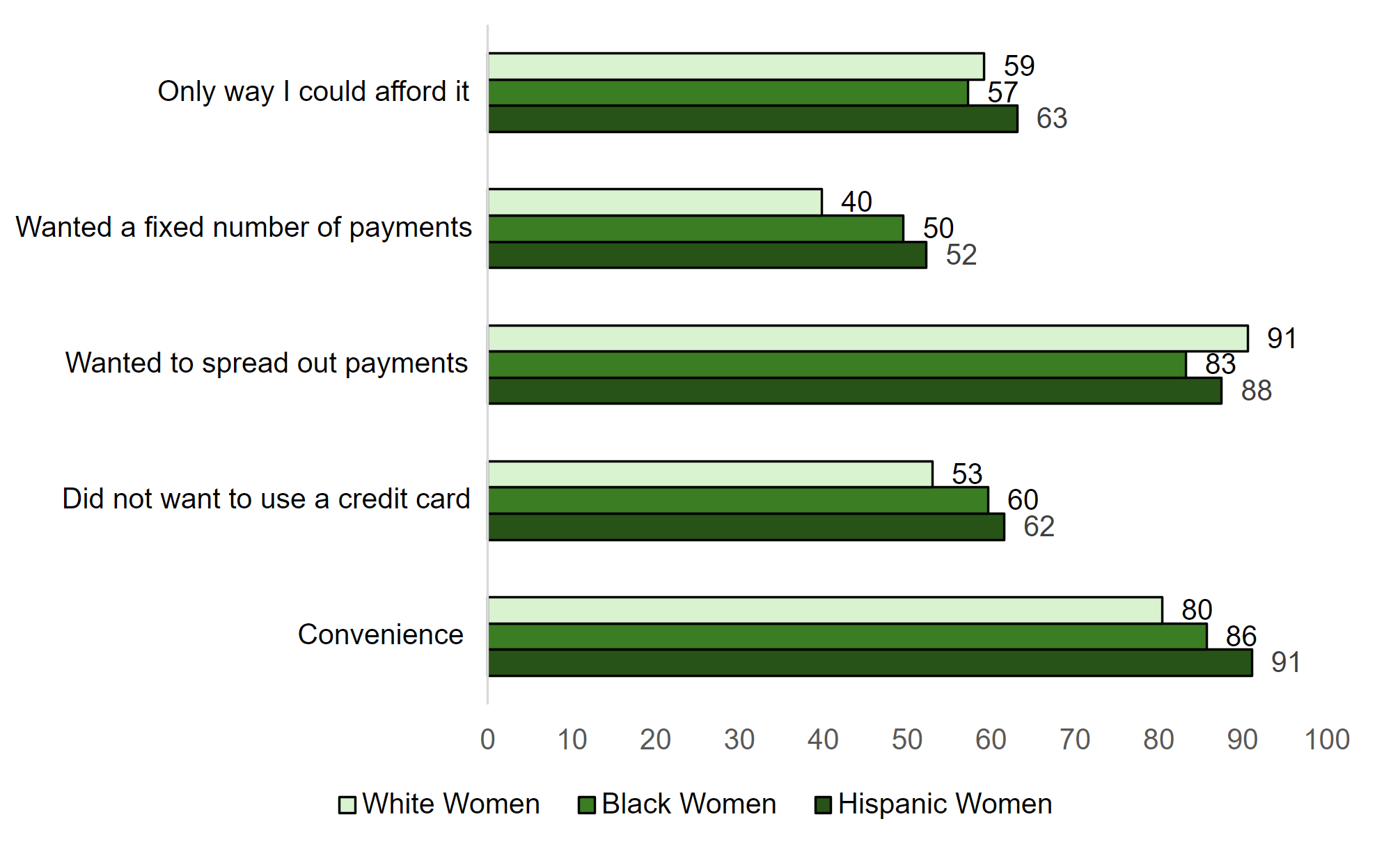

The reasons people cite for using BNPL provides insight into why certain demographic groups use BNPL at higher rates. As noted earlier, Black and Hispanic women are particularly likely to use BNPL. We find evidence that Black and Hispanic women are more likely to prefer BNPL for its convenience and specific product features like a fixed number of payments (Figure 2). Additionally, similar shares of White, Black and Hispanic women cited "the only way I could afford it" as a reason for using BNPL, suggesting that necessity is not the reason Black and Hispanic women use BNPL more frequently than White women.

Note: Key identifies bars in order from left to right, top to bottom.

Source: Authors' calculations using the 2022 and 2023 Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking.

Reasons for using BNPL differed widely by users' financial characteristics. The same groups who were most likely to use BNPL – those who appear liquidity or credit constrained – were also most likely to use BNPL out of necessity.

Among BNPL users who reported "just getting by" or "finding it difficult to get by" financially, 78 percent said they used BNPL because it was the only way they could afford their purchase. Similarly high shares of BNPL users with less than $500 in emergency savings or with family incomes less than $50,000 cited reasons related to necessity as factors in their choice to use BNPL.

In contrast, BNPL users with greater financial resources were more likely to use BNPL to avoid interest charges than out of necessity. For instance, 72 percent of BNPL users with family incomes of $100,000 or more cited avoiding interest charges as a reason for using BNPL, whereas only about one-third cited a reason related to necessity (table 7).

Table 7. Reasons for BNPL Use, by family income

| Reason | Less than $25,000 | $25,000-$49,999 | $50,000-$99,999 | $100,000 or more |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preference or convenience | 83 | 90 | 90 | 89 |

| Convenience | 78 | 86 | 85 | 81 |

| Did not want to use a credit card | 44 | 57 | 59 | 58 |

| Avoid interest charges | 49 | 55 | 61 | 72 |

| Payment timing | 80 | 89 | 93 | 91 |

| Wanted to spread out payments | 77 | 88 | 93 | 91 |

| Wanted a fixed number of payments | 45 | 50 | 47 | 42 |

| Necessity | 71 | 68 | 56 | 34 |

| Only way I could afford it | 70 | 67 | 55 | 32 |

| Only accepted payment method I had | 33 | 23 | 18 | 10 |

Source: Authors' calculations using the 2022 and 2023 Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking.

Among BNPL users who also used AFS credit products (payday loans, pawn shop loans, auto title loans, or tax advance), 82 percent said they used BNPL because it was the only way they could afford their purchase. Additionally, two-thirds of BNPL users who carried an unpaid balance on their credit card most or all of the time reported using BNPL out of necessity, compared with one third who did not carry an unpaid balance on their credit card in the past 12 months (table 8).

Table 8. Reasons for BNPL Use, by AFS and credit card payment behavior in the past 12 months

| Reason | Alternative Financial Service | Credit Card Payment Behavior | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Has used an AFS Credit | Has not used an AFS Credit | Never carried an unpaid balance | Carried an unpaid balance once or some of the time | Carried an unpaid balance most or all of the time | |

| Preference or convenience | 85 | 89 | 83 | 89 | 93 |

| Convenience | 81 | 82 | 77 | 83 | 86 |

| Did not want to use a credit card | 46 | 56 | 38 | 59 | 69 |

| Avoid interest charges | 51 | 61 | 61 | 64 | 64 |

| Payment timing | 84 | 89 | 86 | 89 | 94 |

| Wanted to spread out payments | 80 | 88 | 85 | 86 | 93 |

| Wanted a fixed number of payments | 54 | 45 | 35 | 50 | 51 |

| Necessity | 85 | 52 | 33 | 51 | 67 |

| Only way I could afford it | 82 | 50 | 32 | 50 | 66 |

| Only accepted payment method I had | 41 | 17 | 11 | 21 | 19 |

Source: Authors' calculations using the 2022 and 2023 Survey of Household Economics and Decision making.

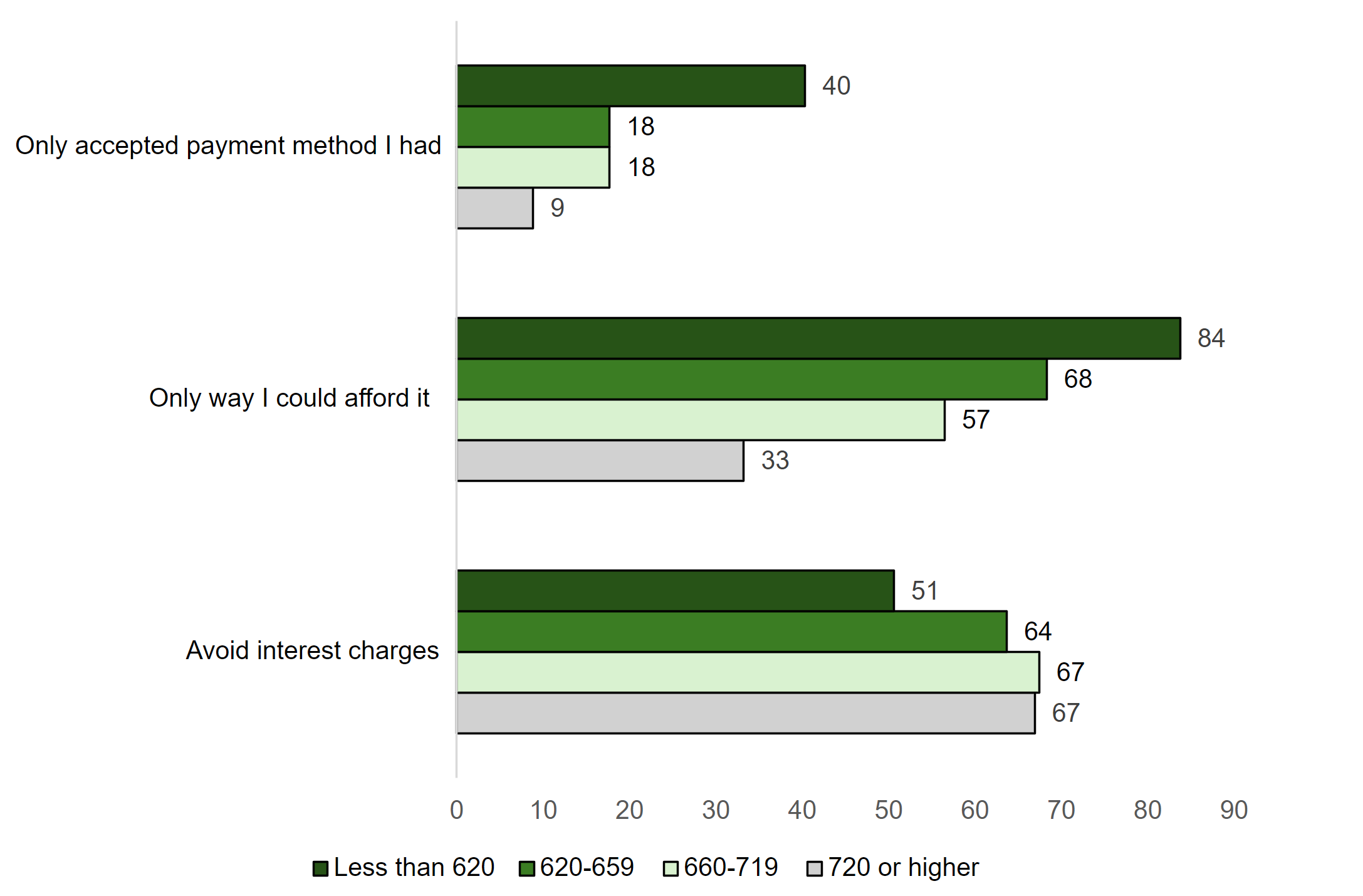

Consistent with the results above, BNPL users with lower credit scores were much more likely cite reasons related to necessity (Figure 3). Additionally, BNPL users with credit scores below 620, were less likely than those with higher credit scores to say they used BNPL to avoid interest charges. This result that users with low credit scores were less focused on interest rates is somewhat puzzling, as those with low credit scores would likely face higher interest rates than those with higher credit scores. That said, the result is consistent with a story of severely liquidity or credit constrained consumers being less sensitive to interest rates. And for those who also say they used BNPL out of necessity, interest charges may not be top of mind.

Note: Key identifies bars in order from left to right, top to bottom.

Source: Authors' calculations using the 2023 SHED credit-merge sample. Credit score is VantageScore 4.0. Among BNPL users.

A related question is whether the BNPL users who say they are doing so out of necessity are also seeking additional credit from other sources. To explore this, we looked at the credit search behaviors and delinquency rates on other credit products based on the reasons that people are using BNPL.

Those who said they used BNPL because it was the only accepted payment method they had applied for credit cards at higher rates (1.32 bankcard and charge card inquiries) than those who cited other reasons for using BNPL. They also had higher incidence of having a delinquent credit card account within the prior year (table 9).

Table 9. Credit searching and repayment behavior, by reason for using BNPL

| Reason | Total number of bankcard revolving and charge inquiries made in the last 12 months | Total number of inquiries made in the last 12 months | Total number of trades presently 30 or more days delinquent or derogatory including collections | Total number of revolving trades ever 30 or more days delinquent or derogatory occurred in the last 12 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preference or convenience | 0.92 | 1.30 | 1.86 | 0.55 |

| Convenience | 0.95 | 1.33 | 1.93 | 0.58 |

| Did not want to use a credit card | 0.98 | 1.39 | 1.88 | 0.60 |

| Avoid interest charges | 0.94 | 1.36 | 1.62 | 0.47 |

| Payment timing | 0.91 | 1.27 | 1.82 | 0.54 |

| Wanted to spread out payments | 0.91 | 1.27 | 1.83 | 0.54 |

| Wanted a fixed number of payments | 1.00 | 1.39 | 2.23 | 0.71 |

| Necessity | 1.07 | 1.48 | 2.29 | 0.68 |

| Only way I could afford it | 1.07 | 1.49 | 2.33 | 0.69 |

| Only accepted payment method I had | 1.32 | 1.80 | 3.34 | 1.00 |

Source: Authors' calculations using the 2023 SHED credit-merge sample. Among BNPL users.

Summary

Consistent with other research, we find that adults under age 60, adults without a bachelor's degree, Black and Hispanic adults, and women were more likely to use BNPL. We also show that BNPL use was particularly high among Black and Hispanic women, yet they were no more likely than White women to report using BNPL out of necessity. Rather, Black and Hispanic women exhibited a greater preference for the specific product features of BNPL, like a fixed number of payments.

Turning to financial characteristics, consumers who appear liquidity or credit constrained were among the most likely to use BNPL and to say they used BNPL, at least in part, because it was the only way they could afford to make their purchase. Those using BNPL out of necessity were also more likely than other users to be seeking credit from other sources. This stood in sharp contrast to users with more financial resources who typically said they used BNPL to spread out payments or avoid interest charges.

Our findings suggest that while BNPL is a convenient payment mechanism that consumers can use to access credit, some financially vulnerable consumers may be overextending themselves by using BNPL to make purchases that they otherwise could not afford. Consequently, further research on the ways that consumers are using the product would be beneficial to understand the longer-term implications for consumers who are using BNPL.

References

Aidala, F., Mangrum, D., & Van der Klaauw, W. (2023). Who Uses "Buy Now, Pay Later?". Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics.

Aidala, F., Mangrum, D., & Van der Klaauw, W. (2024). How and Why Do Consumers Use "Buy Now, Pay Later"?. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics.

Akana, T. (2022). Buy Now, Pay Later: Survey Evidence of Consumer Adoption and Attitudes (PDF). Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

Akana, T., & Doubinko, V. Z. (2024). 4-in-6 Payment Products—Buy Now, Pay Later: Insights from New Survey Data (PDF). Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

Berg, T., Burg, V., Keil, J., & Puri, M. (2023). The Economics of "Buy Now, Pay Later": A Merchant's Perspective. SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4448715

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. (2022). Buy Now, Pay Later: Market Trends and Consumer Impacts (PDF).

deHaan, E., Kim, J., Lourie, B., & Zhu, C. (2022). Buy Now Pay (Pain?) Later. Management Sciences.

Di Maggio, M., Williams, E., & Katz, J. (2022). Buy now, pay later credit: User characteristics and effects on spending patterns, National Bureau of Economic Research, (No. w30508). doi: 10.3386/w30508

Doubinko, V. Z., & Akana, T. (2023). How Does Buy Now, Pay Later Affect Customers' Credit? (PDF). Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Payment Cards Center Discussion Paper, No. DP23-1.

Federal Reserve Board. (2022). Economic Well-being of U.S. Households in 2021. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Federal Reserve Board. (2023). Economic Well-being of U.S. Households in 2022. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Federal Reserve Board. (2024a). Economic Well-being of U.S. Households in 2023. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Federal Reserve Board. (2024b). Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking [dataset] (Washington: Board of Governors).

Shupe, C., Fulford, S., & Li, G. (2023). Consumer Use of Buy Now, Pay Later Insights from the CFPB Making Ends Meet Survey (PDF). Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Office of Research Reports Series, (01).

1. Some risks with BNPL include a lack of disclosure around loan terms and fees and, because BNPL products are not yet reported to traditional credit bureaus, the possibility of an overextension of credit or loan stacking (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 2022). Additionally, BNPL users are typically required to use autopay for their installment payments. BNPL users who do not enough funds in their account to cover their BNPL payment may not only incur a late fee charged by their BNPL provider but may also incur additional overdraft or NSF fees (Lake, 2023). Return to text

2. The questionnaire, anonymized data, and survey methodology for all years are available through the Federal Reserve Board's website at https://www.federalreserve.gov/consumerscommunities/shed.htm. For details on the survey and its methods, see Federal Reserve Board, 2024a). Return to text

3. SHED is administered using the Ipsos KnowledgePanel, which recruits respondents using random address-based sampling. The survey itself is administered online, but internet access and devices are provided for respondents who need them. Although research has previously found that the SHED closely matches the results found using face-to-face or telephone interviews for many questions (Larrimore, Schmeiser, and Devlin-Foltz 2015), it is possible that the online survey administration could upwardly bias the share of adults who have used technologically driven products such as BNPL. Our results for BNPL usage are on the lower end of that found in recent surveys, however, which suggests that this is likely not substantially effecting our results. Return to text

4. See CFPB (2016) for more detail on the credit invisibles. Return to text

5. Other surveys measure BNPL use, although the questions and estimated usage rates vary. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York (Aidala et al., 2023) found 19 percent of adults used BNPL in the prior year and the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia (Akana & Doubinko, 2024) found that 20 percent of adults used BNPL in the previous 3 months in 2023Q4. Return to text

6. In cognitive testing of the SHED BNPL question fielded in 2021 and 2022, several respondents reported false positives because they confused BNPL with installment loans or other products, which could result in an overstatement of BNPL usage. To reduce confusion, in 2023 the question was revised to incorporate the term "pay in four" into the description, although even with this question improvement it is possible that the SHED slightly overstates BNPL use if respondents are considering other forms of borrowing to be BNPL. Return to text

7. Aidala et. al. (2022) does not report findings by race/ethnicity, whereas Akana (2022) and Akana and Doubinko (2024) only differentiate white and nonwhite. Shulpe et. al. (2023) does not report BNPL use among Asian adults. Additionally, Shulpe et. al. (2023) finds that adults with lower educational attainment were less likely to use BNPL, contrary to other studies and SHED. Return to text

8. That said, since 2021, the shares of Asian, Hispanic, and White adults using BNPL have all increased, whereas use among Black adults has remained relatively flat. Return to text

9. It is possible that some of these respondents used BNPL in 2021 or earlier, did not use it in 2022, and then used it again in 2023. Return to text

10. This finding follows results in other previous research that has linked survey data to credit bureau data and found that BNPL users have lower credit scores and worse credit characteristics than non-users (Doubinko & Akana, 2022; Shulpe, Lee, & Fulford, 2023; deHann et al., 2022). Return to text

11. Aidala et. al. (2024) defines the financially fragile as having a credit score below 620, having been declined for a credit application in the past year, or having fallen thirty or more days delinquent on a loan in the past year and defines all other respondents as financially stable. Return to text

12. For this section, we pool the 2022 and 2023 SHED to increase the sample of BNPL users. We do not include the 2021 SHED because the question asking about reasons people used BNPL had different answer choices. Return to text

Larrimore, Jeff, Alicia Lloro, Zofsha Merchant, and Anna Tranfaglia (2024). ""The Only Way I Could Afford It": Who Uses BNPL and Why," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, December 20, 2024, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3675.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.