FEDS Notes

July 11, 2024

The Recent Evolution of the Federal Funds Market and its Dynamics during Reductions of the Federal Reserve's Balance Sheet1

Alyssa Anderson and Dave Na

Following its May 2024 meeting, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announced that it would slow the pace of its balance sheet reduction starting in June 2024.2 This will allow for a more gradual transition from an abundant to ample supply of reserves. As reserves decline, conditions in money markets, including the federal (fed) funds market, will be important in judging whether the supply of reserves is approaching ample. In this note, we discuss the recent evolution of the fed funds market, its participants and their motivations, and its trading dynamics during Federal Reserve balance sheet reduction episodes.

Background and recent evolution of the fed funds market

The fed funds market is an unsecured, mostly overnight, over-the counter funding market among banks and government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs). The fed funds market is an important market for the Federal Reserve because the effective fed funds rate (EFFR), which is calculated as a volume-weighted median of overnight fed funds transactions, is its policy rate. In particular, the FOMC adjusts interest rates by setting a target range for the fed funds rate that reflects the appropriate stance of monetary policy to achieve its longer-run objectives of price stability and maximum employment. Changes in the fed funds target range are the primary means through which the FOMC implements monetary policy.

Prior to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007-2008, the Federal Reserve operated with a limited supply of reserves. In this scarce reserves regime, reserve requirements played a central role in monetary policy implementation by creating a stable demand for reserves, and the Federal Reserve actively managed the supply of reserves in the banking system through open market operations. Banks generally just held required reserves, as determined by reserve requirements, and banks with excess reserves lent in the fed funds market to banks that needed more reserves to meet their reserve requirements. As a result, interbank trading in the fed funds market was active as many banks relied on the market for both funding and reserves management.

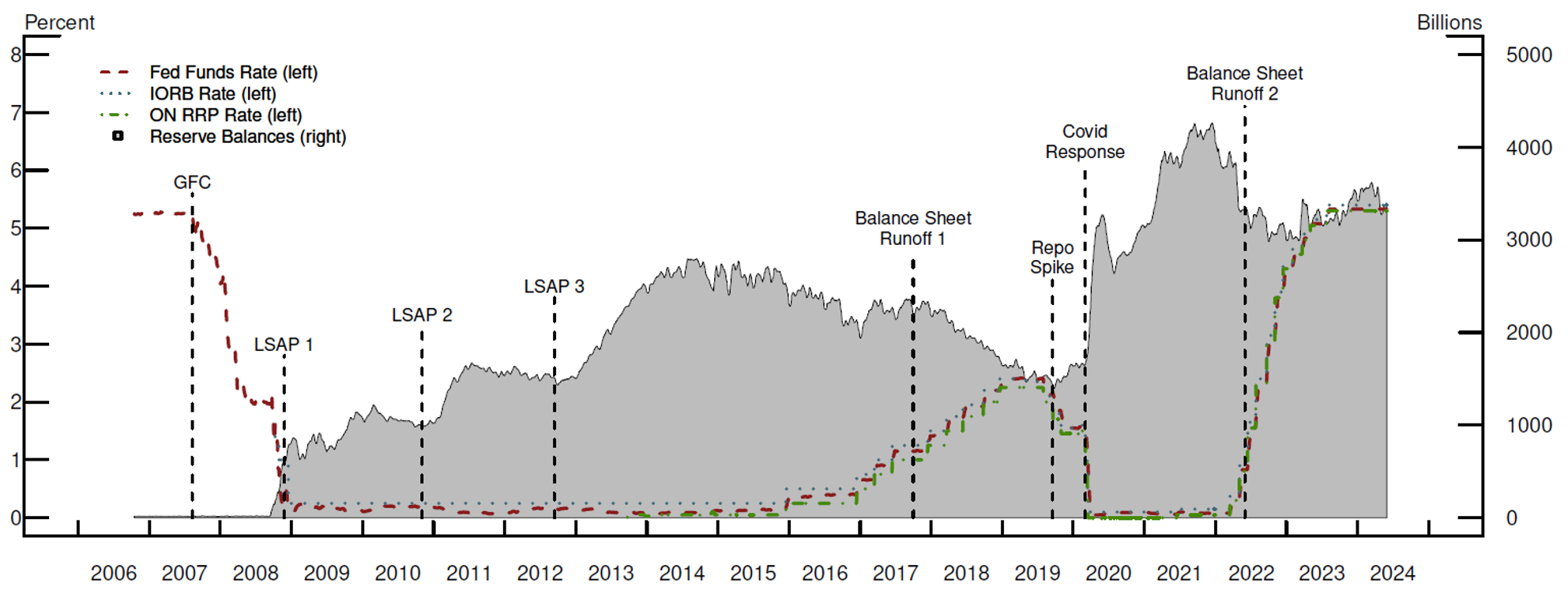

In response to the GFC, the Federal Reserve conducted large-scale asset purchases (LSAPs) to support the U.S. economy once the fed funds rate was at its effective lower bound. These LSAPs expanded the Federal Reserve's balance sheet substantially, which resulted in reserves growing from about $40 billion in 2008 to about $2.8 trillion in 2014 (Figure 1). Given the abundance of reserves resulting from LSAPs, the Federal Reserve started to operate in a floor system and, in 2019, announced that it intends to continue to operate with ample reserves going forward. In an ample reserves regime, the Federal Reserve no longer actively manages the supply of reserves through open market operations. Instead, it sets administered rates—the interest rate on reserve balances (IORB) and the overnight reverse repo facility (ON RRP) offering rate—to implement monetary policy and ensure that the fed funds rate stays within the FOMC's target range.3 Further, in light of the shift to an ample reserves regime, the Federal Reserve reduced banks' required reserves to zero in 2020.4

Note: Fed Funds rate and reserve balances are 10−day rolling averages.

Source: H41, FRBNY.

As a result of these developments, the majority of fed funds trading was no longer motivated by banks' funding needs or reserves management. Instead, the majority of fed funds trading is driven by other trading motivations as discussed in the next section of this note.

Participants and trading motivations

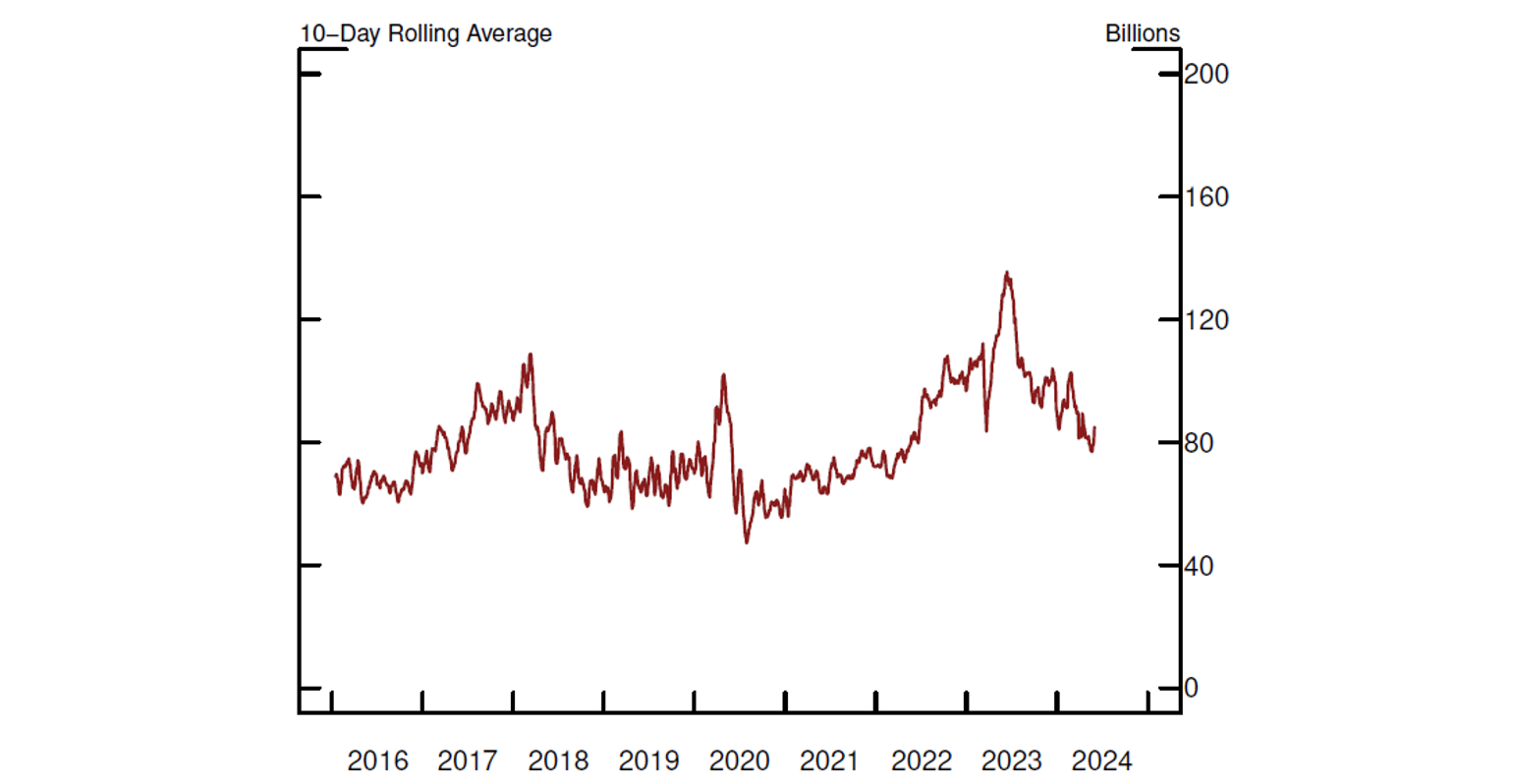

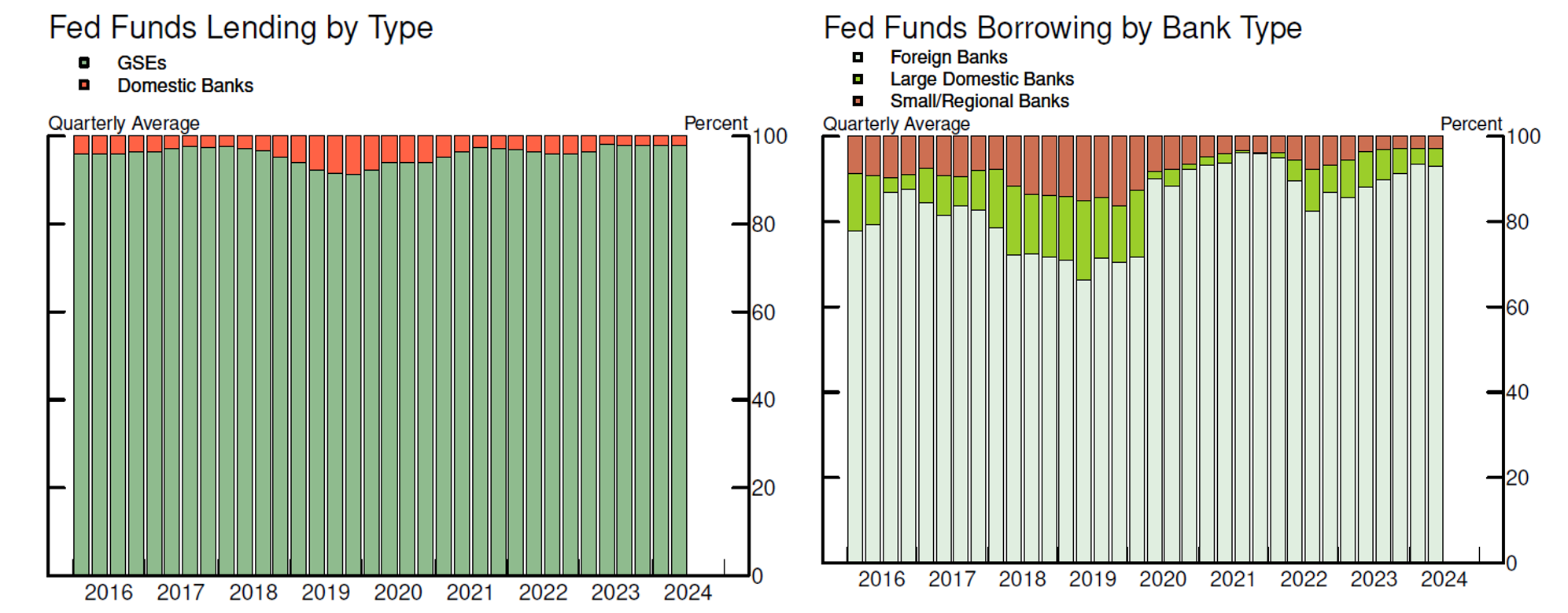

Figure 2 shows total fed funds trading volume, and Figure 3 shows the market share of key lenders and borrowers in the fed funds market. Since the GFC, GSEs, especially Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs), have become the primary lenders of fed funds. They account for, on average, about 97% of lending volume, and their market share has been fairly stable over time, as seen in the left panel of Figure 3. FHLBs are required to hold a certain amount of liquid assets including U.S. Treasuries and other short-term investments like fed funds, repo, and interest-bearing deposit accounts as a part of their liquidity management strategy.5 However, unlike banks, they are not eligible to earn IORB on their deposits at the Federal Reserve, so they lend in the fed funds market to earn a return on cash balances. As of early 2024, FHLBs' lending in the fed funds market has typically been at an average rate of about 7 basis points below IORB.

Domestic banks, including custodian banks and banker's banks, make up the remaining fed funds lending and typically only lend to small domestic banks. As of early 2024, their average rate was about 8 basis points above IORB as they do not have an incentive to lend below IORB and often lend to smaller, less creditworthy banks.

Source: FR2420.

Left chart

Note: Key identifies in order from bottom to top. Source: FR2420.

Right chart

Note: Small/regional banks have less than $100B in assets, while large banks have more than $100B in assets. Key identifies in order from bottom to top.

Source: FR2420, NIC Data, Call Report.

On the borrowing side, as shown in the right panel of Figure 3, U.S. branches and agencies of foreign banks (referred to as foreign banks herein) account for the majority of borrowing in the fed funds market. As of early 2024, their share is around 90% of transaction volume, but this fraction varies over time with market liquidity conditions. Their primary motivation is to earn the spread between the rate on fed funds and IORB. That is, foreign banks borrow in the fed funds market, at around 7 basis points below IORB, then place that cash at the Federal Reserve to earn IORB. This trade is mainly done by foreign banks rather than domestic banks because domestic banks are subject to FDIC fees on the total size of their assets minus equity, which makes such a trade less profitable.6

Foreign banks also borrow for funding or other investment strategies.7 When the Federal Reserve reduced the size of its balance sheet in 2017-2019, EFFR increased relative to IORB, which reduced and eventually eliminated the profitability of the IORB trading strategy. As a result, many foreign banks scaled back their fed funds borrowing, but only a few banks left the market altogether, suggesting that they had a genuine need to borrow or other trading strategies that were still profitable even with relatively high fed funds rates.

The second largest group of borrowers is large domestic banks, which we define as those with more than $100 billion in assets. A key motivation for these banks, which is also relevant for large foreign banks, is to improve their Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR). Specifically, large banks are required to hold a certain amount of high-quality liquid assets relative to their expected cash outflows. In calculating the LCR, borrowings are assumed to have different paces of outflows, or run-off rates, depending on their characteristics, including lending counterparty. That is, some borrowings are assumed to be more persistent than others over an assumed 30-day stress scenario. FHLBs are preferred counterparties because they have a lower assumed run-off rate for the LCR calculation.8 As shown by Anderson and Tase (2023), banks that must report their LCR daily are willing to pay higher rates to borrow in fed funds relative to other banks in order to improve their LCRs. However, they do not do so in other funding markets, such as the Eurodollar market, which do not have LCR-preferred counterparties.

The smallest group of borrowers—small and regional domestic banks, which we define as domestic banks with less than $100 billion in assets—trade more for traditional reserves management. Their market share varies over time, with lower market liquidity leading to higher volumes. In particular, as aggregate reserves decline, there is more competition for reserves and smaller banks increasingly need to borrow to obtain the reserves they need. As of early 2024, small and regional domestic banks trade at minimal volume, but their volume is expected to increase as the Federal Reserve's balance sheet reduction continues.

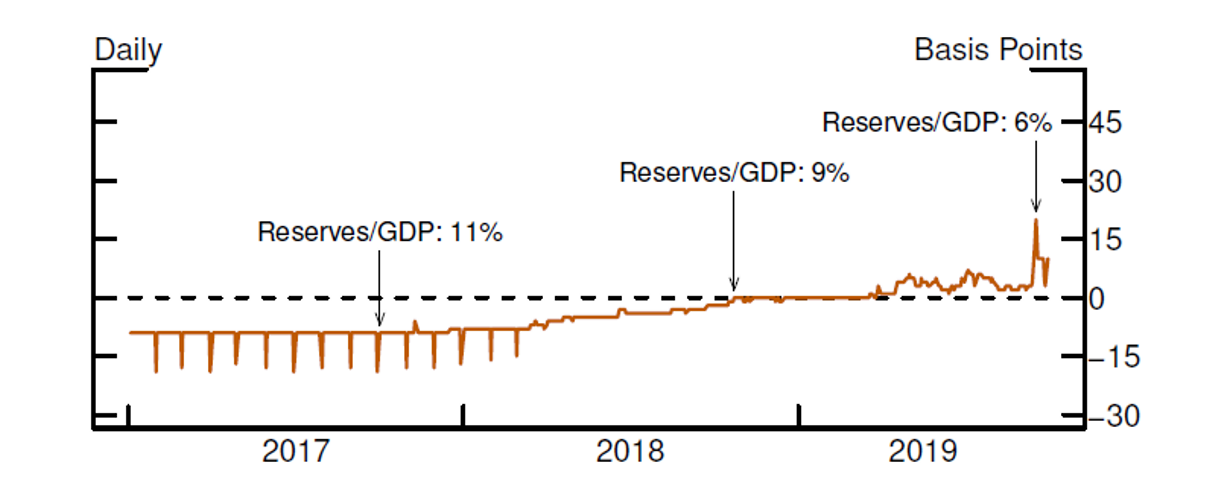

Fed funds during the balance sheet reduction episode of 2017-2019

By 2017, the U.S. economy had recovered following the GFC, so the Federal Reserve began normalizing monetary policy. This included a gradual increase in the fed funds target range and letting Treasury securities and agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) roll off the Federal Reserve's System Open Market Account (SOMA) portfolio.9 During the course of balance sheet reduction from October 2017 to July 2019, reserves fell from about 11% of nominal GDP to about 7% of nominal GDP.10,11 Correspondingly, EFFR moved higher and eventually started trading above IORB (Figure 4).12 This process led to changes in trading dynamics among fed funds market participants.

Source: FRBNY, Federal Reserve Board, Bureau of Economic Analysis

First, as rates in other overnight funding markets such as Treasury repo moved higher relative to fed funds rates starting in spring 2018, FHLBs shifted some of their lending away from fed funds to repo. This led to a reduction in overall fed funds volume (Figure 2). Correspondingly, foreign banks reduced their borrowing, both given the reduction in lending from FHLBs, which reduced the amount available for foreign banks to borrow, and later as EFFR moved closer to IORB, which made fed funds borrowing less profitable.

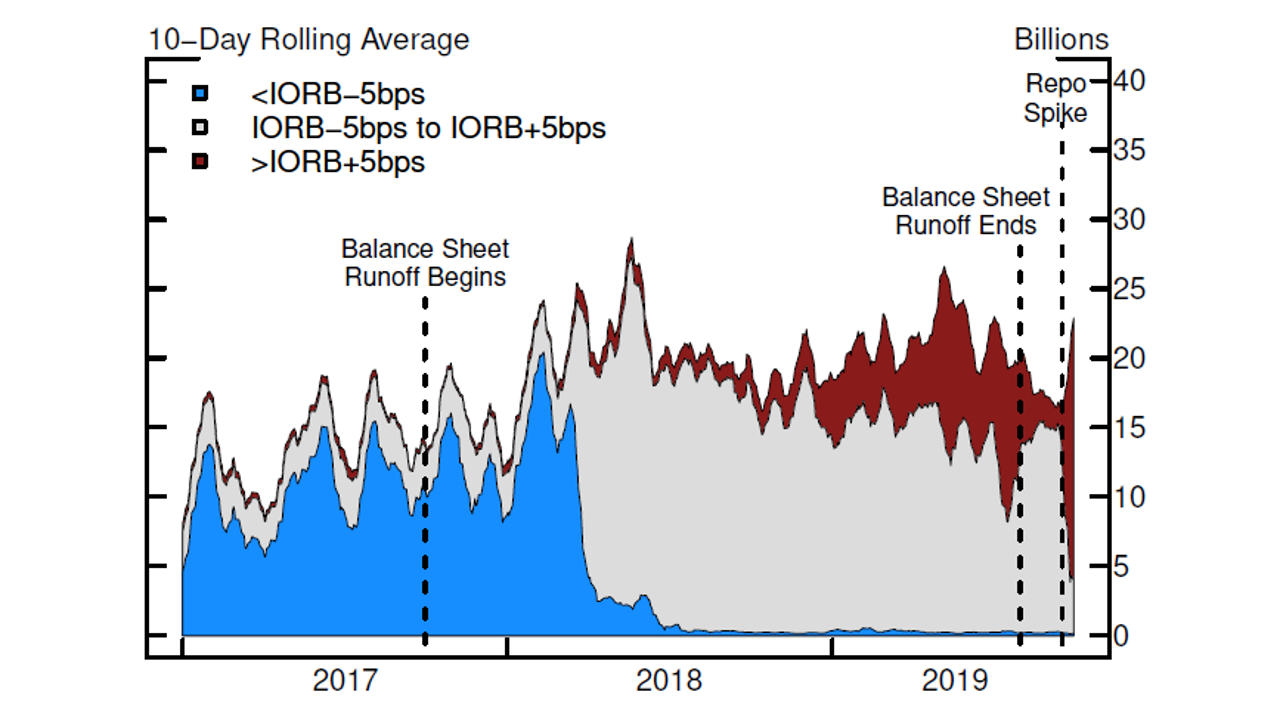

In contrast to foreign banks, domestic banks increased their borrowing as balance sheet reduction proceeded, with their market share reaching about 30% (Figure 3). Their borrowing was primarily driven by traditional liquidity/reserves management as competition for reserves increased as reserves declined. Correspondingly, domestic bank behavior in the fed funds market was an early indicator of reserves becoming less abundant. In addition to borrowing more, domestic banks (especially regional banks) also started borrowing at rates above IORB regularly in mid-2018 (Figure 5).13

Note: Key identifies in order from bottom to top. Vertical lines show balance sheet runoff begins on 10/2/2017, balance sheet runoff ends on 8/1/2019 and repo spike on 9/17/2019.

Source: FR2420, NIC Data.

After balance sheet reduction ended in July 2019, reserves continued to decline given increases in other Federal Reserve liabilities, leading to increased competition for reserves (Copeland et al. (2021), Afonso et al. (2023), and Lopez-Salido and Vissing-Jorgensen (2023)). Additionally, in the repo market, there was relatively less cash available to be lent while demand to borrow was very high, leading to strains in the repo market (Anbil et al. (2024)). These dynamics culminated in the repo stress episode of mid-September 2019, which also affected the fed funds market.14 Short-term interest rate control was affected as EFFR printed outside the target range for one day. Specifically, EFFR was 2.3% on September 17 when the target range was 2.0 to 2.25%. While this was nowhere near the spike seen in the repo market—the secured overnight financing rate (SOFR) printed at 5.25%—the move in EFFR prompted Federal Reserve action to bring rates back down.15 This event highlights that stress in other short-term funding markets can spill over to the fed funds market. While fed funds is generally very stable, it is still susceptible to movements in other money markets.

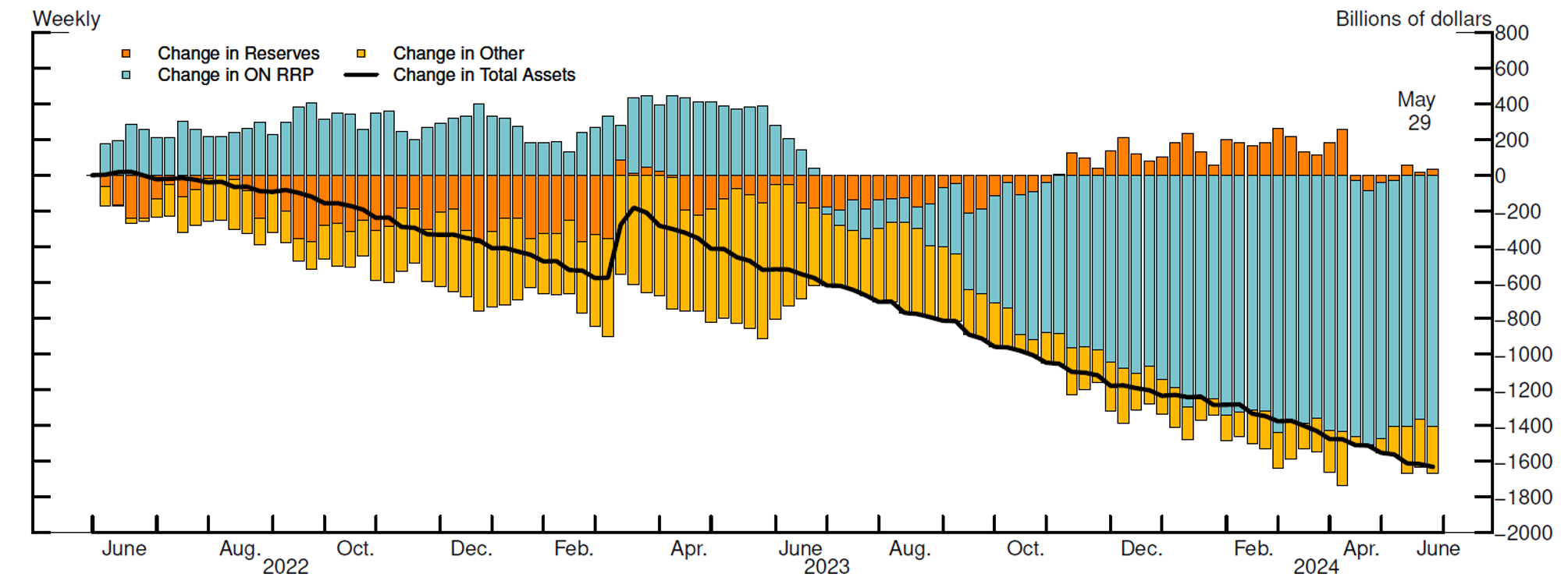

Fed funds during the balance sheet reduction episode of 2022 to present

At the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Federal Reserve undertook asset purchases to support financial market functioning and the economy.16 With the recovery in full swing, the Federal Reserve began its balance sheet reduction in June 2022.17 As of May 2024, reserves remain around 12% of nominal GDP, which is about where they started this balance sheet reduction episode (Figure 1).18 Despite some volatility over time, reserves are largely unchanged since the effects of balance sheet reduction on net have instead mainly been offset by reduction in the ON RRP (Figure 6). In this environment of still abundant reserves, there haven't been any notable changes to the fed funds market or broader money market conditions yet.

Note: Values are cumulative changes since June 1, 2022. Other represents all liabilities plus capital excluding reserves and ON RRP.

Source: H41.

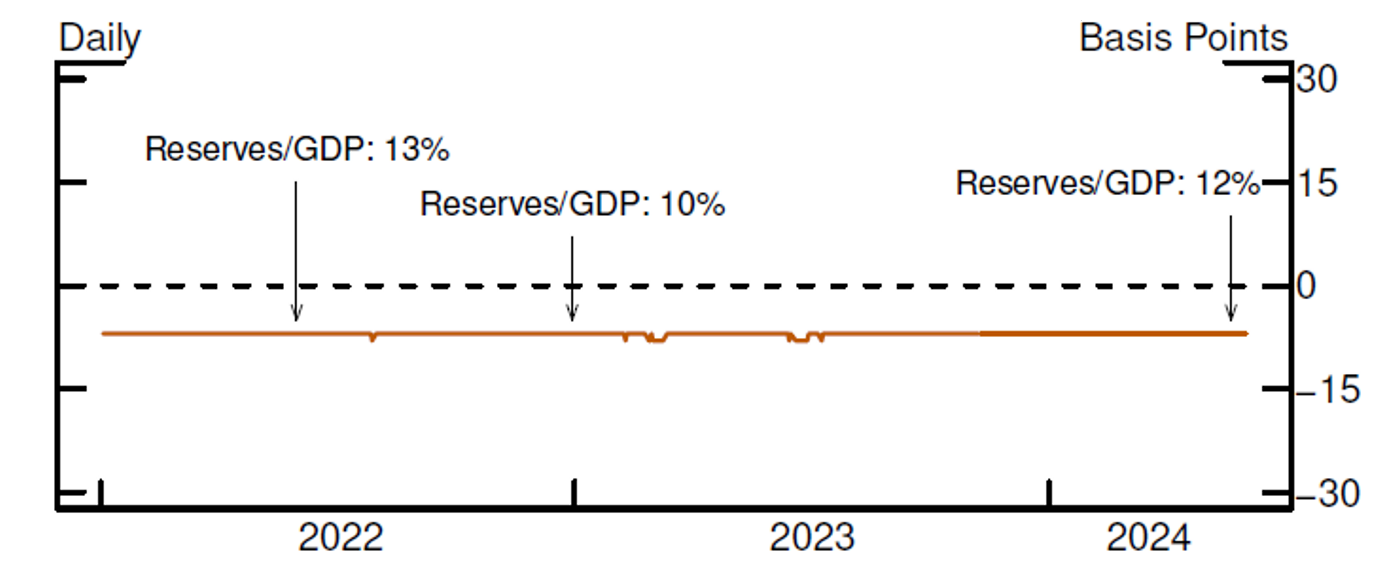

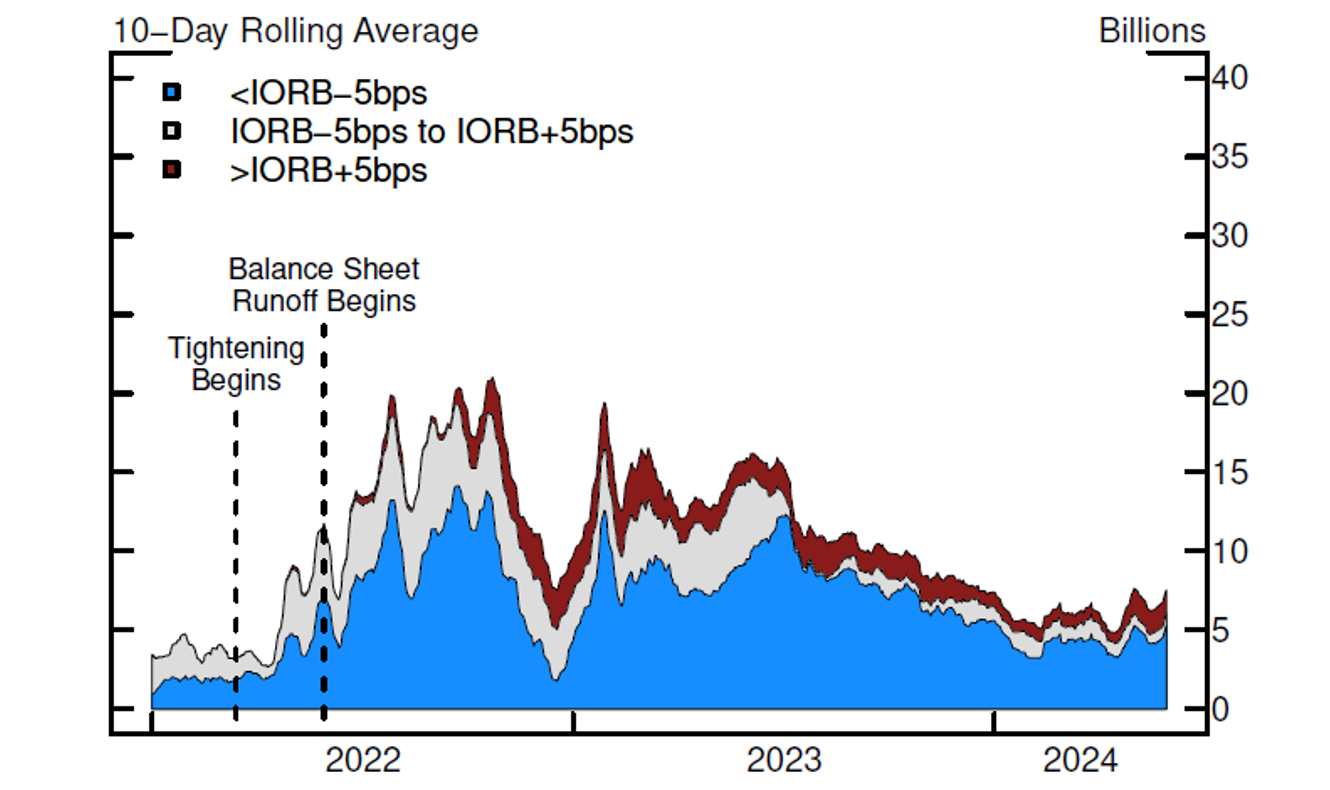

As shown in Figure 7, the EFFR-IORB spread is unchanged at 7 basis points, despite modest increases in repo rates amid higher repo volumes and significant Treasury bill issuance. As of early 2024, domestic bank borrowing in the fed funds market remains small at about $5 billion per day on average (Figure 8). These banks are paying somewhat high rates relative to IORB, as denoted by the red area in Figure 8, but this is typical for the types of banks that are borrowing.

Source: FRBNY, Federal Reserve Board, Bureau of Economic Analysis

Note: Key identifies in order from bottom to top. Vertical line shows tightening begins on 3/17/2022 and balance sheet runoff begins on 6/1/2022.

Source: FR2420, NIC Data.

Figure 8 also highlights some significant developments unrelated to the Federal Reserve's balance sheet reduction. First, there was a notable increase in daily volume in mid-2022 when domestic banks increased their borrowing from less than $5 billion to about $20 billion per day. Aggregate market volume also increased from around $70 billion to $100 billion per day (Figure 2). The increase in borrowing by domestic banks was mainly to offset deposit outflows amid increases in the policy rate. As interest rates increased, deposits flowed out of banks into money funds and other investments since bank deposit rates are sticky and do not increase as quickly as other short-term interest rates.19 As a result, large regional banks needed to borrow more in fed funds to compensate, but this dynamic subsequently retraced as banks adjusted to the high interest rate environment. Second, fed funds volumes increased again in early 2023 as a result of the regional banking crisis. While aggregate volume dropped sharply immediately after the seizure of Silicon Valley Bank in mid-March, it rose to over $140 billion per day in June 2023 before retracing (Figure 2). This increase was driven in part by some domestic banks borrowing for precautionary reasons amid large deposit outflows from certain regional banks.20

Looking ahead, as balance sheet reduction continues, we expect to see similar market dynamics in the fed funds market as last time. That is, we expect to see a narrowing of the spread between EFFR and IORB. Further, there should be more trading volume at or above IORB as well as more borrowing from domestic banks at potentially higher rates.21 There is still significant uncertainty as to when this will happen, but it is likely that it will not happen until reserves reach a sufficiently low level reflecting the effects of the balance sheet reduction. As reserves decline, days on which reserves temporarily drop, including tax payment dates and reporting dates such as quarter-ends, will be key watch points.22

Given the uncertainty regarding the level of reserves consistent with operating in an ample reserves regime, the FOMC's decision to slow the pace of balance sheet reduction beginning in June 2024 should help ensure a smooth transition from abundant to ample reserve balances.23 A slower pace should allow more time for financial institutions and short-term funding markets, including the fed funds market, to adjust to lower levels of reserves, while also giving more time for the Federal Reserve to assess the evolution of reserve demand and market conditions.

References

Afonso, Gara, Marco Cipriani, Adam Copeland, Anna Kovner, Gabriele La Spada, and Antoine Martin, 2020, The market events of mid-September 2019, Staff report, Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Afonso, Gara, Gabriele La Spada, Thomas M. Mertens, and John C. Williams, 2023, The optimal supply of central bank reserves under uncertainty, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report 1077.

Anbil, Sriya, Alyssa Anderson, Ethan Cohen, and Romina Ruprecht, 2024, Stop believing in reserves, Working paper, SSRN.

Anbil, Sriya, Alyssa Anderson, and Zeynep Senyuz, 2020, What happened in money markets in September 2019?, FEDS Notes Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, February 27, 2020.

Anderson, Alyssa, Wenxin Du, and Bernd Schlusche, 2021, Arbitrage capital of global banks, NBER working paper 28658.

Anderson, Alyssa and Manjola Tase, 2023, LCR premium and the federal funds market, Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2023-071, Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Copeland, Adam, Darrell Duffie, and Yilin (David) Yang, 2021, Reserves were not so ample after all, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report 974.

Driscoll, John C., and Ruth A. Judson, 2013, Sticky deposit rates, Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2013-80, Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Ihrig, Jane, Zeynep Senyuz, and Gretchen C. Weinbach, 2020, The Fed's "ample-reserves" approach to implementing monetary policy, Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2020-022, Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Lopez-Salido, David, and Annette Vissing-Jorgensen, 2023, Reserve demand, interest rate control, and quantitative tightening, Working paper, Federal Reserve Board.

1. Andy Xia provided excellent research assistance. We thank David Bowman, Jim Clouse, Chris Gust, Sebastian Infante, and Zeynep Senyuz for their useful comments and suggestions. The views expressed in this note are our own, and do not necessarily represent the views of the Board of Governors or the Federal Reserve System. Return to text

2. See the May 2024 FOMC statement. Return to text

3. IORB, which was introduced in 2008, is the rate that depository institutions earn on their reserve balances at the Federal Reserve. The ON RRP, which was introduced in 2013, helps set a floor under overnight interest rates by providing an alternative investment for a broad set of institutions who cannot earn IORB, including money funds, primary dealers, and GSEs. These institutions can lend to the Federal Reserve via the ON RRP and earn the ON RRP offering rate. See Ihrig et. al. (2020) for further information on the Federal Reserve's ample reserves framework. Return to text

4. See the March 15, 2020 Federal Reserve press release. Return to text

5. See Federal Home Loan Bank Liquidity Guidance for further information on FHLB liquidity. Return to text

6. See the FDIC Deposit Insurance Fund Assessment Methodology & Rates for more information on the FDIC fee. Return to text

7. One such strategy is covered-interest rate parity arbitrage, in which banks typically borrow unsecured, short-term dollar funding from markets such as fed funds and then lend these dollars in the FX forward/swap markets. See Anderson, Du, and Schlusche (2021) for further information on foreign banks' arbitrage strategies. Return to text

8. See the BIS executive summary of the LCR and Basel III: The Liquidity Coverage Ratio and liquidity risk monitoring tools for further information on the calculation of the LCR and run-off rates. Return to text

9. The FOMC announced that it would gradually reduce the Federal Reserve's securities holdings by decreasing its reinvestment of the principal payments received from securities held in the SOMA. See the Addendum to the Policy Normalization Principles and Plans for more detail. Return to text

10. While the Federal Reserve does not target reserves-to-nominal-GDP, scaling reserves by nominal GDP provides a useful way to compare reserve levels over time. Alternative measures include reserves-to-bank-assets and reserves-to-deposits. Return to text

11. As shown in Figure 4, reserves were about 11% of nominal GDP at the start of balance sheet reduction in 2017, about 9% of nominal GDP when EFFR reached IORB, and about 6% of nominal GDP at the repo spike of mid-September 2019. Return to text

12. Note that EFFR used to drop several basis points on month-ends prior to early 2018. This was due to foreign banks reducing their borrowing in fed funds on these dates for regulatory reporting purposes. The remaining borrowers in the market would only borrow at lower rates. This dynamic stopped in early 2018 in part due to many jurisdictions moving away from month- and quarter-end snapshots to daily averages for their regulatory reporting. Return to text

13. Figure 5 shows domestic bank borrowing volume categorized by the rate paid relative to IORB. The blue region shows the amount of borrowing volume done at low rates—IORB minus 5 basis points or less—while the red region shows the volume done at high rates—IORB plus 5 basis points or more. Return to text

14. See Anbil et al. (2020) and Afonso et al. (2020) for detailed explanations of what happened in repo markets in mid-September 2019. Return to text

15. To help maintain the fed funds rate within its target range, the Federal Reserve began conducting daily repo operations on September 17, 2019. See the Federal Reserve Bank of New York's Statement Regarding Repurchase Operation for details on the first of these operations. Return to text

16. See the related FOMC statements for more information on these asset purchases: https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20200315a.htm and https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20201216a.htm. Return to text

17. See the May 2022 Plans for Reducing the Size of the Federal Reserve's Balance Sheet. Return to text

18. As shown in Figure 7, reserves were about 13% of nominal GDP at the start of balance sheet reduction in 2022, reached a low of about 10% of nominal GDP at year-end 2022, and are about 12% of nominal GDP as of the end of May 2024. Return to text

19. See Driscoll and Judson (2013) for more information on the stickiness of bank deposit rates. Return to text

20. There was also an increase in lending supply from FHLBs as they were increasing their liquidity buffers in order to be able to provide advances to their member banks as needed. FHLBs lend to their member banks via advances. In anticipation of increased advance demand, they typically hold additional money in liquid assets, including fed funds, that they can lend as needed. Return to text

21. In addition to dynamics in the fed funds market, other indictors of reserve demand will also provide important information on how balance sheet reduction is proceeding. See the May 8, 2024 speech from SOMA Manager Roberto Perli for further information on indicators of reserve demand, including 1) the timing of interbank payments, 2) the amount of daylight overdrafts, and 3) the share of repo volume trading at or above IORB. Return to text

22. On tax payment dates, money is withdrawn by individuals and corporations from banks and money funds in order to pay taxes. As a result, reserves decrease and the Treasury General Account (TGA), the Treasury's operating account at the Fed, increases. On reporting dates, dealers and banks reduce their borrowing in funding markets. As a result, lenders such as money funds turn to the ON RRP, leading the ON RRP to increase and reserves to decrease. Return to text

23. See the March 2024 and May 2024 FOMC meeting minutes for the Committee's discussions of slowing the pace of balance sheet reduction. Return to text

Anderson, Alyssa, and Dave Na (2024). "The Recent Evolution of the Federal Funds Market and its Dynamics during Reductions of the Federal Reserve's Balance Sheet," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, July 11, 2024, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3548.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.