FEDS Notes

June 27, 2023

The Transmission of Global Risk

Martin Bodenstein, Pablo Cuba-Borda, Albert Queralto1

Introduction

Turmoil in the banking sector in the U.S. and Europe in early 2023 brought jitters to financial markets and increased concerns about a global risk-off event. Risk-off episodes—periods of increased global risk aversion—are characterized by sharp increases in credit spreads, high volatility in equity markets, and appreciation of reserve currencies.

We identify changes in global risk sentiment using data on the excess bond premium (EBP) introduced in Gilchrist and Zakrajsek (2012). First, we show that changes in the EBP predict popular proxies for global risk such as the VIX index or the BBB corporate spread. Second, employing structural vector auto regressions (SVARs), we find that identified innovations in the EBP have statistically significant and sizable effects on the global economy: a 1.5 percentage point increase in the EBP—as in the lead-up to the dot-com bubble burst, or between the summer of 2007 and the near-failure of Bear Stearns in March 2008—takes 1 percentage point off world inflation and 2 percent off the level of world GDP over the year following the global risk shock. We propose a mechanism based on the differentiated demand for safe assets to rationalize the empirical findings from the SVAR within a large class of open-economy DSGE models.

The Excess Bond Premium and Proxies for Global Risk

Gilchrist and Zakrajsek (2012) show that the excess bond premium (EBP), an indicator that measures risk appetite in U.S. corporate bond markets, is a good predictor of future economic activity in the U.S.2 Because of the global importance of the U.S. financial sector, we explore whether the EBP also predicts well-known proxies of global risk sentiment.

Panel A of Figure 1 plots the EBP from January 2000 to February 2023. Sharp movements in the EBP coincide with major risk-off episodes of widespread financial stress or heightened uncertainty about the global economic outlook. Panels B-D of Figure 1 show that risk-off episodes are also associated with sharp movements in other financial variables, such as greater stock market volatility as captured by the VIX index, higher borrowing costs as reflected in BBB corporate bond spreads in the U.S. and abroad, and lower values of the "GFC factor" of Miranda-Agrippino and Rey (2020)—a measure of the common component driving the valuation in risky asset prices globally.

Sources: Excess bond premium from Favara et al. (2016). VIX index obtained from FRED. Corporate spreads constructed using ICE Data Indices, LLC, with permission, and Bloomberg Finance LP, Bloomberg Per Security Data License. GFC factor from Miranda-Agrippino and Rey (2020).

To formally test the predictive content of the EBP for subsequent movements in other proxies for global risk, we estimate the following regression:

$$$$ Y_{t+h} - Y_{t-1} = \alpha + \sum_{i=1}^{p} \beta_i \Delta Y_{t-i} + \gamma \Delta EBP_t + \epsilon_{t+h}$$$$

where $$Y_{t+h}$$ denotes the value of the variable of interest h-periods into the future. We compute the predictive content of the EBP for the proxies for global risk shown in Figure 1: (i) BBB-corporate borrowing spreads for the U.S. and the foreign economies, (ii) the VIX index, (iii) the GFC factor.

Table 1 summarizes our findings. The columns correspond to each of the proxies of global risk, and the rows report the estimates of the parameter of interest, $$\gamma$$, for horizons h={3, 6, 12} months. The EBP emerges as a good predictor of the change in other proxies of global risk at all three horizons. For example, at h=3, that is, three months later, a one percentage point increase in the EBP leads to a 0.3 percentage point decline in the GFC factor, a 0.7 percentage point increase in U.S. spreads, a 1 percentage point increase in foreign spreads, and a 9 percent increase in the VIX. Our results suggest that the EBP is an even more useful indicator than previously shown, in that it predicts global risk in addition to real activity and turning points in the economic cycle.3

Table 1 Forecasting Proxies of Global Risk: $$\gamma$$ estimates

| Horizon (h) | Dependent Variable: | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFC Factor (p.p.) | U.S. Spreads (p.p.) | Foreign Spreads (p.p.) | VIX (%) | |

| 3 | -0.78*** | 0.70*** | 0.95*** | 8.92*** |

| 6 | -0.94*** | 0.71*** | 1.06*** | 8.06*** |

| 12 | -1.01*** | 0.66*** | 0.87*** | 7.67*** |

This table depicts the estimates of the predictive effect of the EBP on different proxies of Global Risk. All impacts are analyzed at 3, 6 and 12 months in the future. For all time horizons, an increase in the EBP predicts a reduction on the GFC Factor. An increase of the EBP is associated with an increase on U.S. and foreign corporate spreads. Also, an increase in the EBP predicts an increase in the VIX. All estimated coefficients in the regressions are statistically significant at the 1% level.

Quantifying the Effects of a Global Risk Episode: A Structural VAR Scenario

Having established the EBP as a predictor for other global risk proxies, we estimate a monthly VAR that includes the EBP, the VIX index, 5-year BBB corporate bond spreads in the U.S. and foreign economies, the trade-weighted broad real dollar index, total PCE inflation for the U.S., headline CPI inflation for the foreign economies, and monthly estimates of U.S. and foreign real GDP.4 The dollar index and GDP series are detrended before estimation. Our estimation sample covers the period 2001m8 – 2023m1. We do not include the GFC factor because it is only available through 2019m4. To identify global risk shocks in the VAR, we impose a recursive contemporaneous causal structure with variables in the order listed above.

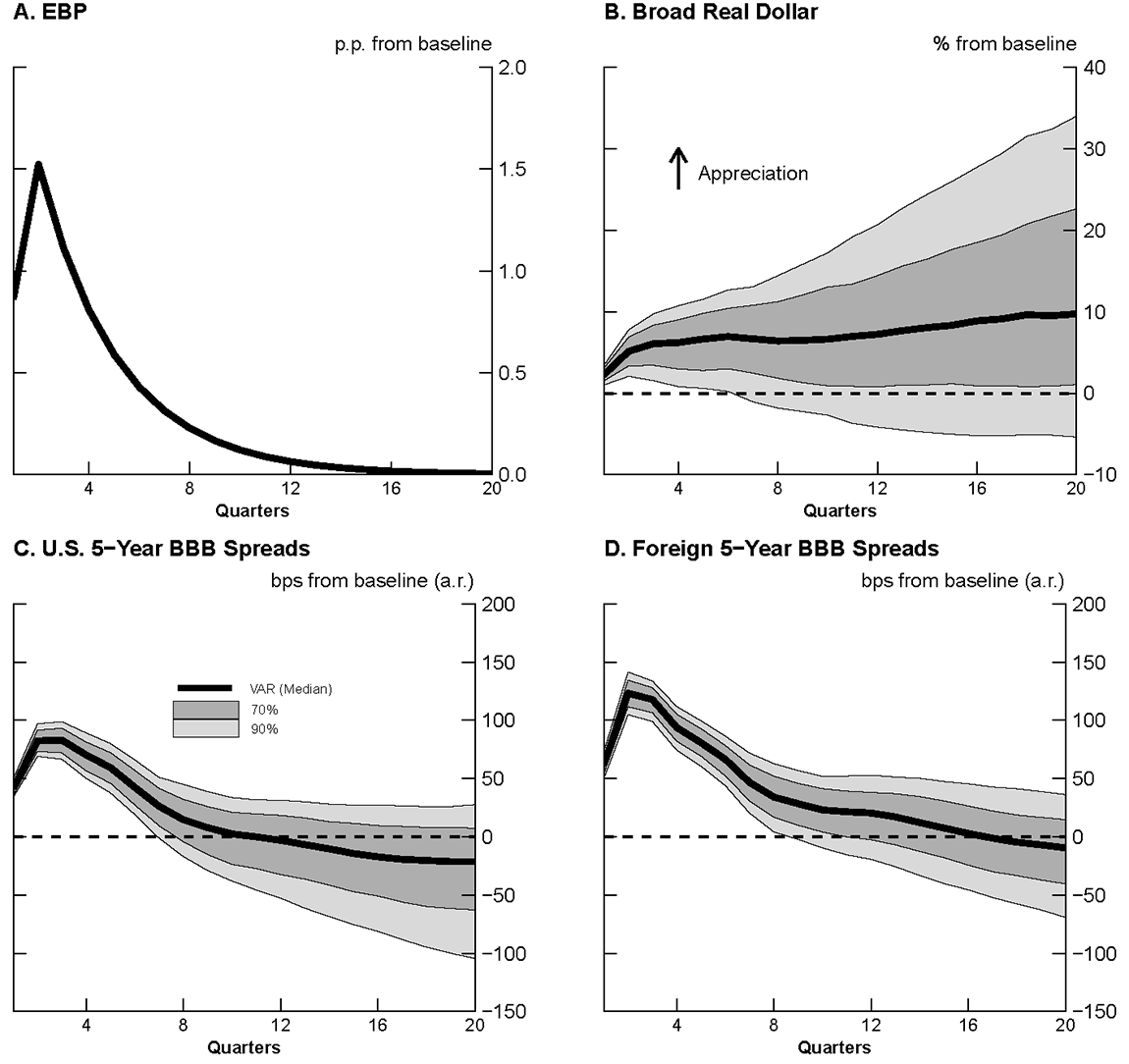

To illustrate the effects of increased global risk, we build a scenario calibrated to the initial phase of the Global Financial Crisis. Focusing on a scenario—as opposed to merely plotting impulse responses—provides useful perspective by sizing the shock to replicate a well-known historical event. Accordingly, using the methodology proposed in Antolin-Diaz et al. (2021), we mimic the run-up of the EBP of 1.5 percentage points that occurred between the summer of 2007 until the near failure of Bear Stearns in March 2008. Figure 2 displays the response of key financial variables in this scenario. The top left panel shows the path of the EBP across all simulations. By construction, this path has no uncertainty as we target a given path of the EBP. The increase in global risk results in a 15 percent increase in the VIX (not shown). The broad real dollar index appreciates nearly 5 percent within the first year, and corporate borrowing spreads in the U.S. increase by about 100 basis points and remain elevated for several quarters. Corporate borrowing spreads in the rest of the world increase by even more than in the United States because borrowing spreads for emerging market economies in international markets are particularly sensitive to changes in global risk sentiment.

Note: The solid black line corresponds to the median response across simulations. We report end-of-quarter values from monthly simulations. Confidence bands are obtained by bootstrapping. The dark and light shaded gray areas denote the 70 and 90 percent confidence intervals, respectively.

Figure 3 shows the effects of the increase in global risk on economic activity and inflation. The top panel shows that, economic activity declines persistently worldwide, with the median estimate showing a 2 percent decline in the level of GDP relative to trend followed by a very slow rebound. The distribution of responses shows substantial downside risk, particularly abroad. The 95th percentile of our simulations suggest that economic activity in the foreign economies could experience a near-permanent decline in the level of GDP, while the upper 5th percentile shows an only moderate and delayed recovery. Turning to inflation, in the bottom panels, weaker global activity and lower oil prices (not shown) reduce headline inflation in the United States and abroad by about 1 percentage point. In addition, the appreciation of the dollar lowers the price of U.S. imports and also contributes to the decline in headline inflation.

Note: The solid black line corresponds to the median response across simulations. The dark and light shaded gray areas denote the 70 and 90 percent confidence intervals, respectively.

A Structural Model with Global Risk

In this final section, we propose a mechanism based on the differentiated demand for safe assets to rationalize the empirical findings from the SVAR in a large class of open-economy DSGE models. To this end, we introduce a "Global Flight-to-Safety" (GFS) shock, denoted $$\zeta^{GFS}_{t}$$, that captures the emergence of global risk. We consider an economy with two countries, home (h), which represents the United States, and foreign (f), which represents the rest of the world. Each country issues a non-state-contingent bond denominated in its own currency, denoted by $$B^H_t,B^F_t $$. There is time variation in the utility that households in both countries derive from holding these safe bonds, with higher values of $$\zeta^{GFS}_{t}$$ associated with higher marginal utility. Global investors arbitrage across bonds denominated in different currencies, and in a global flight-to-safety episode they obtain extra utility from holding U.S. bonds:5

$$$$ Utility\ from\ B^F_t = \zeta^{GFS}_{t} \times B^F_t $$$$

$$$$ Utility\ from\ B^H_t = (1 + \theta) \times \zeta^{GFS}_{t} \times B^H_t $$$$

If $$ \theta > 0$$, our model features an asymmetry: an increase in $$\zeta^{GFS}_{t}$$ raises global investors' utility from U.S. bond holdings more than it raises utility from foreign bond holdings. The asymmetric and time-varying relative demand for U.S. bonds induced by the GFS shock is consistent with the recent empirical and theoretical literature on the role of deviations from uncovered interest rate parity (UIP) emanating from the special role of the dollar and flight-to-safety concerns—see Valchev (2020), Lilley et al. (2020), Kekre and Lenel (2023), Akinci, Kalemli-Ozcan, and Queralto (2023), Fukui, Nakamura, and Steinsson (2023), among others.

The central intuition of our mechanism is conveyed by the following equations:6

$$$$ (1)\ E_t (\hat{c}^h_{t+1} - \hat{c}^h_t) = \hat{r}^h_t + \hat{\zeta}^{GFS}_{t} $$$$

$$$$ (2)\ E_t (\hat{c}^f_{t+1} - \hat{c}^f_t) = \hat{r}^f_t + \hat{\zeta}^{GFS}_{t} $$$$

$$$$ (3)\ E_t (\hat{q}_{t+1} - \hat{q}_t) = \hat{r}^f_t - \hat{r}^h_t - \theta \hat{\zeta}^{GFS}_{t} $$$$

where all variables with a hat denote log-deviations from steady-state, and $$E_t$$ is the time-t expectation operator. Domestic consumption is denoted by $$\hat{c}^h_t$$, and the ex-ante real interest rate is $$ \hat{r}^h_t $$. The foreign counterparts are $$ \hat{c}^f_t , \hat{r}^f_t $$. The real exchange rate is denoted by $$ \hat{q}_t $$ and measures the relative price of the U.S. consumption basket in terms of the foreign consumption basket. An increase in $$ \hat{q}_t $$ thus corresponds to a real appreciation of the dollar.

Equations (1) and (2) are the optimality conditions for the intertemporal consumption allocation at home and abroad, respectively. The GFS shock shifts the marginal utility of bond holdings and creates a wedge in the Euler equations of both countries. Intuitively, with future consumption determined by long-run real interest rates, a GFS shock that increases the global demand for safe assets reduces global consumption today. Hence, the GFS shock is a risk-premium shock that triggers a global slowdown. Equation (3) is a modified Uncovered Interest Parity (UIP) condition that emerges as global investors arbitrage the returns between home and foreign bonds. The UIP condition states that when U.S. real interest rates are higher than abroad, the real dollar is expected to depreciate in the future, to compensate investors for the lower return of holding foreign bonds. An increase in global risk, captured by a GFS shock, is also associated with an expected depreciation of the real dollar. For this depreciation to take place in the future, $$ \hat{q}_t $$ must increase on impact, translating into an appreciation of the real dollar in response to increased global risk. In our model, the GFS shock enters the UIP condition in the form of a "wedge" as in the work of Itskhoki and Mukhin (2021).7 Deviations from UIP caused by the GFS shock, however, are not disconnected from the macroeconomy. The appreciation of the dollar accompanies a slowdown in global aggregate demand, a decline in asset prices, and an increase in borrowing costs.

In separate work, we embed this mechanism into an estimated dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) international macro model (Bodenstein et al. 2023).8 Figure 4 plots the impulse responses for selected variables to the GFS shock in that model. The GFS shock increases corporate borrowing spreads in the United States and abroad and induces an appreciation of the U.S. real dollar. As global financial conditions tighten, the interest rate sensitive components of GDP, consumption, and investment, drop sharply, with the foreign effects more pronounced reflecting the steeper increase in borrowing spreads—consistent with the reorientation of financial flows towards safe U.S. assets. The magnitude of the responses to the GFS shock in our DSGE model are in line with the elasticities implied by a shock to the EBP in the SVAR analysis.

Note: Impulse responses to $$ \hat{\zeta}^{GFS}_{t} $$ shock calibrated to produce 100 basis point increase in U.S. corporate spreads. All responses are computed at the posterior mean of the estimated parameters.

Conclusions

We show that the excess bond premium (EBP) predicts popular proxies for global risk such as the VIX index, the BBB corporate spread and the GFC factor. We use the EBP to identify global risk shocks that generate increases in corporate spreads across country blocs, high volatility in equity markets, and an appreciation of the real U.S. dollar. The increased global risk aversion, in turn, triggers a decline in global economic activity and a significant drop in inflation. We show that an open-economy model in which dollar-denominated bonds play a special role in international financial markets can rationalize the empirical findings associated with global risk-off episodes.

References

Akinci, O., S. Kalemli-Ozcan, and A. Queralto, 2023. "Uncertainty Shocks, Capital Flows, and International Risk Spillovers". Mimeo.

Antolín-Díaz, J., I. Petrella, J. F. Rubio-Ramírez, 2021. "Structural scenario analysis with SVARs," Journal of Monetary Economics, Elsevier, vol. 117(C), pages 798-815.

Bodenstein, M., P. Cuba-Borda, N. Gornemann, I. Presno, A. Prestipino, A. Queralto, A. Raffo, 2023. "Risk Shocks, the Dollar, and Global Business Cycles." Mimeo.

Cuba-Borda, P., A. Mechanick, and A. Raffo, 2018. "Monitoring the World Economy: A Global Conditions Index," IFDP Notes 2018-06-15, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Favara, G., S. Gilchrist, K. F. Lewis, and E. Zakrajšek, 2016. "Recession Risk and the Excess Bond Premium," FEDS Notes 2016-04-08, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Fisher, J. 2015. "On the Structural Interpretation of the Smets–Wouters "Risk Premium" Shock," Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Blackwell Publishing, vol. 47(2-3), pages 511-516.

Gilchrist, S., and E. Zakrajsek, 2012. "Credit Spreads and Business Cycle Fluctuations," American Economic Review, American Economic Association, vol. 102(4), pages 1692-1720.

Itskhoki, O., and D. Mukhin, 2021. "Exchange Rate Disconnect in General Equilibrium," Journal of Political Economy, University of Chicago Press, vol. 129(8), pages 2183-2232.

Kekre, K., and M. Lenel, 2021. "The Flight to Safety and International Risk Sharing," NBER Working Papers 29238, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Lilley, A., M. Maggiori, B. Neiman, and J. Schreger, 2022. "Exchange Rate Reconnect," The Review of Economics and Statistics, MIT Press, vol. 104(4), pages 845-855.

Miranda-Agrippino, S., and H. Rey, 2020. "U.S. Monetary Policy and the Global Financial Cycle," Review of Economic Studies, Oxford University Press, vol. 87(6), pages 2754-2776.

Fukui, M., E. Nakamura, and J. Steinsson, 2023 "The Macroeconomic Consequences of Exchange Rate Depreciations". University of California, Berkely. Mimeo.

Valchev, R. 2020. "Bond Convenience Yields and Exchange Rate Dynamics." American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 12 (2): 124-66.

1. All authors are affiliated with the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington D.C., 20551 USA. We would like to thank Thomas Kaupas, Mike McHenry, and Mikael Scaramucci for excellent research assistance. Return to text

2. The EBP measures the component of U.S. corporate credit spreads that is not directly attributable to expected risk of default and thus to news about future cash flows. Return to text

3. See Favara, et al. (2016) and Cuba-Borda, Mechanick, and Raffo (2018). Return to text

4. The foreign GDP and inflation aggregates are constructed from country-level data of major advanced and emerging economies representing over 80 percent of world GDP, and aggregated using trade-shares with respect to the U.S. We follow Cuba-Borda, Mechanick, and Raffo (2018) to construct monthly estimates of real GDP for the U.S. and the foreign bloc. Return to text

5. This relation can be obtained easily assuming a separable-additive utility in consumption and bond holdings. Return to text

6. For simplicity, we assume household utility to be additive separability in consumption and leisure and log-utility for consumption. The $$ GFS $$ shock is different from a country-specific risk-premium shock in the spirit of Fischer (2015) because it affects the allocation of funds between safe and risky assets in both countries simultaneously. Return to text

7. In Itskhoki and Mukhin (2021), however, the shock that causes this UIP wedge does not enter equations (1) or (2). Return to text

8. The model features the United States and a foreign bloc that represents the major trading partners of the U.S. The model is estimated using data from 1985-2019. The model features a rich set of real and nominal rigidities as well as financial frictions and includes the financial shock of Itskhoki and Mukhin (2021), amongst other structural shocks. Return to text

Bodenstein, Martin, Pablo Cuba-Borda, and Albert Queralto (2023). "The Transmission of Global Risk," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, June 27, 2023, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3327.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.