A bank's total risk-weighted assets would be the sum of its credit risk-weighted assets and risk-weighted assets for operational risk, minus the sum of its excess eligible credit reserves (that is, its eligible credit reserves in excess of its total ECL) not included in tier 2 capital and allocated transfer risk reserves.

To calculate credit risk-weighted assets, a bank must group its exposures into four general categories: wholesale, retail, securitization, and equity. It must also identify assets not included in an exposure category and any non-material portfolios of exposures to which the bank elects not to apply the IRB framework. In order to exclude a portfolio from the IRB framework, a bank must demonstrate to the satisfaction of its primary Federal supervisor that the portfolio (when combined with all other portfolios of exposures that the bank seeks to exclude from the IRB framework) is not material to the bank.

The proposed rule defines a wholesale exposure as a credit exposure to a company, individual, sovereign or governmental entity (other than a securitization exposure, retail exposure, or equity exposure).38 The term "company" is broadly defined to mean a corporation, partnership, limited liability company, depository institution, business trust, SPE, association, or similar organization. Examples of a wholesale exposure include: (i) a non-tranched guarantee issued by a bank on behalf of a company;39 (ii) a repo-style transaction entered into by a bank with a company and any other transaction in which a bank posts collateral to a company and faces counterparty credit risk; (iii) an exposure that the bank treats as a covered position under the MRA for which there is a counterparty credit risk charge in section 32 of the proposed rule; (iv) a sale of corporate loans by a bank to a third party in which the bank retains full recourse; (v) an OTC derivative contract entered into by a bank with a company; (vi) an exposure to an individual that is not managed by the bank as part of a segment of exposures with homogeneous risk characteristics; and (vii) a commercial lease.

The agencies are proposing two subcategories of wholesale exposures – HVCRE exposures and non-HVCRE exposures. Under the proposed rule, HVCRE exposures would be subject to a separate IRB risk-based capital formula that would produce a higher risk-based capital requirement for a given set of risk parameters than the IRB risk-based capital formula for non-HVCRE wholesale exposures. An HVCRE exposure is defined as a credit facility that finances or has financed the acquisition, development, or construction of real property, excluding facilities used to finance (i) one- to four-family residential properties or (ii) commercial real estate projects where: (A) the exposure's LTV ratio is less than or equal to the applicable maximum supervisory LTV ratio in the real estate lending standards of the agencies;40 (B) the borrower has contributed capital to the project in the form of cash or unencumbered readily marketable assets (or has paid development expenses out-of-pocket) of at least 15 percent of the real estate's appraised "as completed" value; and (C) the borrower contributed the amount of capital required before the bank advances funds under the credit facility, and the capital contributed by the borrower or internally generated by the project is contractually required to remain in the project throughout the life of the project.

Once an exposure is determined to be HVCRE, it would remain an HVCRE exposure until paid in full, sold, or converted to permanent financing. After considering comments received on the ANPR, the agencies are proposing to retain a separate IRB risk-based capital formula for HVCRE exposures in recognition of the high levels of systematic risk inherent in some of these exposures. The agencies believe that the revised definition of HVCRE in the proposed rule appropriately identifies exposures that are particularly susceptible to systematic risk. Question 24: The agencies seek comment on how to strike the appropriate balance between the enhanced risk sensitivity and marginally higher risk-based capital requirements obtained by separating HVCRE exposures from other wholesale exposures and the additional complexity the separation entails.

The New Accord identifies five sub-classes of specialized lending for which the primary source of repayment of the obligation is the income generated by the financed asset(s) rather than the independent capacity of a broader commercial enterprise. The sub-classes are project finance, object finance, commodities finance, income-producing real estate, and HVCRE. The New Accord provides a methodology to accommodate banks that cannot meet the requirements for the estimation of PD for these exposure types. The sophisticated banks that would apply the advanced approaches in the United States should be able to estimate risk parameters for specialized lending exposures, and therefore the agencies are not proposing a separate treatment for specialized lending beyond the separate IRB risk-based capital formula for HVCRE exposures specified in the New Accord.

In contrast to the New Accord, the agencies are not including in this proposed rule an adjustment that would result in a lower risk weight for a loan to a small- and medium-size enterprise (SME) that has the same risk parameter values as a loan to a larger firm. The agencies are not aware of compelling evidence that smaller firms with the same PD and LGD as larger firms are subject to less systematic risk. Question 25: The agencies request comment and supporting evidence on the consistency of the proposed treatment with the underlying riskiness of SME portfolios. Further, the agencies request comment on any competitive issues that this aspect of the proposed rule may cause for U.S. banks.

Under the proposed rule a retail exposure would generally include exposures (other than securitization exposures or equity exposures) to an individual or small business that are managed as part of a segment of similar exposures, that is, not on an individual-exposure basis. Under the proposed rule, there are three subcategories of retail exposure: (i) residential mortgage exposures; (ii) QREs; and (iii) other retail exposures. The agencies propose generally to define residential mortgage exposure as an exposure that is primarily secured by a first or subsequent lien on one-to-four-family residential property.41 This includes both term loans and revolving home equity lines of credit (HELOCs). An exposure primarily secured by a first or subsequent lien on residential property that is not one-to-four family would also be included as a residential mortgage exposure as long as the exposure has both an original and current outstanding amount of no more than $1 million. There would be no upper limit on the size of an exposure that is secured by one-to-four-family residential properties. To be a residential mortgage exposure, the bank must manage the exposure as part of a segment of exposures with homogeneous risk characteristics. Residential mortgage loans that are managed on an individual basis, rather than managed as part of a segment, would be categorized as wholesale exposures.

QREs would be defined as exposures to individuals that are (i) revolving, unsecured, and unconditionally cancelable by the bank to the fullest extent permitted by Federal law; (ii) have a maximum exposure amount (drawn plus undrawn) of up to $100,000; and (iii) are managed as part of a segment with homogeneous risk characteristics. In practice, QREs typically would include exposures where customers' outstanding borrowings are permitted to fluctuate based on their decisions to borrow and repay, up to a limit established by the bank. Most credit card exposures to individuals and overdraft lines on individual checking accounts would be QREs.

The category of other retail exposures would include two types of exposures. First, all exposures to individuals for non-business purposes (other than residential mortgage exposures and QREs) that are managed as part of a segment of similar exposures would be other retail exposures. Such exposures may include personal term loans, margin loans, auto loans and leases, credit card accounts with credit lines above $100,000, and student loans. The agencies are not proposing an upper limit on the size of these types of retail exposures to individuals. Second, exposures to individuals or companies for business purposes (other than residential mortgage exposures and QREs), up to a single-borrower exposure threshold of $1 million, that are managed as part of a segment of similar exposures would be other retail exposures. For the purpose of assessing exposure to a single borrower, the bank would aggregate all business exposures to a particular legal entity and its affiliates that are consolidated under GAAP. If that legal entity is a natural person, any consumer loans (for example, personal credit card loans or mortgage loans) to that borrower would not be part of the aggregate. A bank could distinguish a consumer loan from a business loan by the loan department through which the loan is made. Exposures to a borrower for business purposes primarily secured by residential property would count toward the $1 million single-borrower other retail business exposure threshold.42

The residual value portion of a retail lease exposure is excluded from the definition of an other retail exposure. A bank would assign the residual value portion of a retail lease exposure a risk-weighted asset amount equal to its residual value as described in section 31 of the proposed rule.

The proposed rule defines a securitization exposure as an on-balance sheet or off-balance sheet credit exposure that arises from a traditional or synthetic securitization. A traditional securitization is a transaction in which (i) all or a portion of the credit risk of one or more underlying exposures is transferred to one or more third parties other than through the use of credit derivatives or guarantees; (ii) the credit risk associated with the underlying exposures has been separated into at least two tranches reflecting different levels of seniority; (iii) performance of the securitization exposures depends on the performance of the underlying exposures; and (iv) all or substantially all of the underlying exposures are financial exposures. Examples of financial exposures are loans, commitments, receivables, asset-backed securities, mortgage-backed securities, corporate bonds, equity securities, or credit derivatives. For purposes of the proposed rule, mortgage-backed pass-through securities guaranteed by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac (whether or not issued out of a structure that tranches credit risk) also would be securitization exposures.43

A synthetic securitization is a transaction in which (i) all or a portion of the credit risk of one or more underlying exposures is transferred to one or more third parties through the use of one or more credit derivatives or guarantees (other than a guarantee that transfers only the credit risk of an individual retail exposure); (ii) the credit risk associated with the underlying exposures has been separated into at least two tranches reflecting different levels of seniority; (iii) performance of the securitization exposures depends on the performance of the underlying exposures; and (iv) all or substantially all of the underlying exposures are financial exposures. Accordingly, the proposed definition of a securitization exposure would include tranched cover or guarantee arrangements – that is, arrangements in which an entity transfers a portion of the credit risk of an underlying exposure to one or more other guarantors or credit derivative providers but also retains a portion of the credit risk, where the risk transferred and the risk retained are of different seniority levels.44

Provided that there is a tranching of credit risk, securitization exposures also could include, among other things, asset-backed and mortgage-backed securities; loans, lines of credit, liquidity facilities, and financial standby letters of credit; credit derivatives and guarantees; loan servicing assets; servicer cash advance facilities; reserve accounts; credit-enhancing representations and warranties; and CEIOs. Securitization exposures also could include assets sold with retained tranched recourse. Both the designation of exposures as securitization exposures and the calculation of risk-based capital requirements for securitization exposures will be guided by the economic substance of a transaction rather than its legal form.

As noted above, for a transaction to constitute a securitization transaction under the proposed rule, all or substantially all of the underlying exposures must be financial exposures. The proposed rule includes this requirement because the proposed securitization framework was designed to address the tranching of the credit risk of exposures to which the IRB framework can be applied. Accordingly, a specialized loan to finance the construction or acquisition of large-scale projects (for example, airports and power plants), objects (for example, ships, aircraft, or satellites), or commodities (for example, reserves, inventories, precious metals, oil, or natural gas) generally would not be a securitization exposure because the assets backing the loan typically would be nonfinancial assets (the facility, object, or commodity being financed). In addition, although some structured transactions involving income-producing real estate or HVCRE can resemble securitizations, these transactions generally would not be securitizations because the underlying exposure would be real estate. Consequently, exposures resulting from the tranching of the risks of nonfinancial assets are not subject to the proposed rule's securitization framework, but generally are subject to the proposal's rules for wholesale exposures. Question 26: The agencies request comment on the appropriate treatment of tranched exposures to a mixed pool of financial and non-financial underlying exposures. The agencies specifically are interested in the views of commenters as to whether the requirement that all or substantially all of the underlying exposures of a securitization be financial exposures should be softened to require only that some lesser portion of the underlying exposures be financial exposures.

The proposed rule defines an equity exposure to mean:

(i) A security or instrument whether voting or non-voting that represents a direct or indirect ownership interest in, and a residual claim on, the assets and income of a company, unless: (A) the issuing company is consolidated with the bank under GAAP; (B) the bank is required to deduct the ownership interest from tier 1 or tier 2 capital; (C) the ownership interest is redeemable; (D) the ownership interest incorporates a payment or other similar obligation on the part of the issuing company (such as an obligation to pay periodic interest); or (E) the ownership interest is a securitization exposure.

(ii) A security or instrument that is mandatorily convertible into a security or instrument described in (i).

(iii) An option or warrant that is exercisable for a security or instrument described in (i).

(iv) Any other security or instrument (other than a securitization exposure) to the extent the return on the security or instrument is based on the performance of security or instrument described in (i). For example, a short position in an equity security or a total return equity swap would be characterized as an equity exposure.

Nonconvertible term or perpetual preferred stock generally would be considered wholesale exposures rather than equity exposures. Financial instruments that are convertible into an equity exposure only at the option of the holder or issuer also generally would be considered wholesale exposures rather than equity exposures provided that the conversion terms do not expose the bank to the risk of losses arising from price movements in that equity exposure. Upon conversion, the instrument would be treated as an equity exposure.

The agencies note that, as a general matter, each of a bank's exposures will fit in one and only one exposure category. One principal exception to this rule is that equity derivatives generally will meet the definition of an equity exposure (because of the bank's exposure to the underlying equity security) and the definition of a wholesale exposure (because of the bank's credit risk exposure to the counterparty). In such cases, as discussed in more detail below, the bank's risk-based capital requirement for the derivative generally would be the sum of its risk-based capital requirement for the derivative counterparty credit risk and for the underlying exposure.

With the introduction of an explicit risk-based capital requirement for operational risk, issues arise about the proper treatment of operational losses that could also be attributed to either credit risk or market risk. The agencies recognize that these boundary issues are important and have significant implications for how banks would compile loss data sets and compute risk-based capital requirements under the proposed rule. Consistent with the treatment in the New Accord, the agencies propose treating operational losses that are related to market risk as operational losses for purposes of calculating risk-based capital requirements under this proposed rule. For example, losses incurred from a failure of bank personnel to properly execute a stop loss order, from trading fraud, or from a bank selling a security when a purchase was intended, would be treated as operational losses.

The agencies generally propose to treat losses that are related to both operational risk and credit risk as credit losses for purposes of calculating risk-based capital requirements. For example, where a loan defaults (credit risk) and the bank discovers that the collateral for the loan was not properly secured (operational risk), the bank's resulting loss would be attributed to credit risk (not operational risk). This general separation between credit and operational risk is supported by current U.S. accounting standards for the treatment of credit risk.

The proposed exception to this standard is retail credit card fraud losses. More specifically, retail credit card losses arising from non-contractual, third party-initiated fraud (for example, identity theft) are to be treated as external fraud operational losses under this proposed rule. All other third party-initiated losses are to be treated as credit losses. Based on discussions with the industry, this distinction is consistent with prevailing practice in the credit card industry, with banks commonly considering these losses to be operational losses and treating them as such for risk management purposes.

Question 27: The agencies seek commenters' perspectives on other loss types for which the boundary between credit and operational risk should be evaluated further (for example, with respect to losses on HELOCs).

Positions currently subject to the MRA include all positions classified as trading consistent with GAAP. The New Accord sets forth additional criteria for positions to be eligible for application of the MRA. The agencies propose to incorporate these additional criteria into the MRA through a separate notice of proposed rulemaking concurrently published in the Federal Register. Advanced approaches banks subject to the MRA would use the MRA as amended for trading exposures eligible for application of the MRA. Advanced approaches banks not subject to the MRA would use this proposed rule for all of their exposures. Question 28: The agencies generally seek comment on the proposed treatment of the boundaries between credit, operational, and market risk.

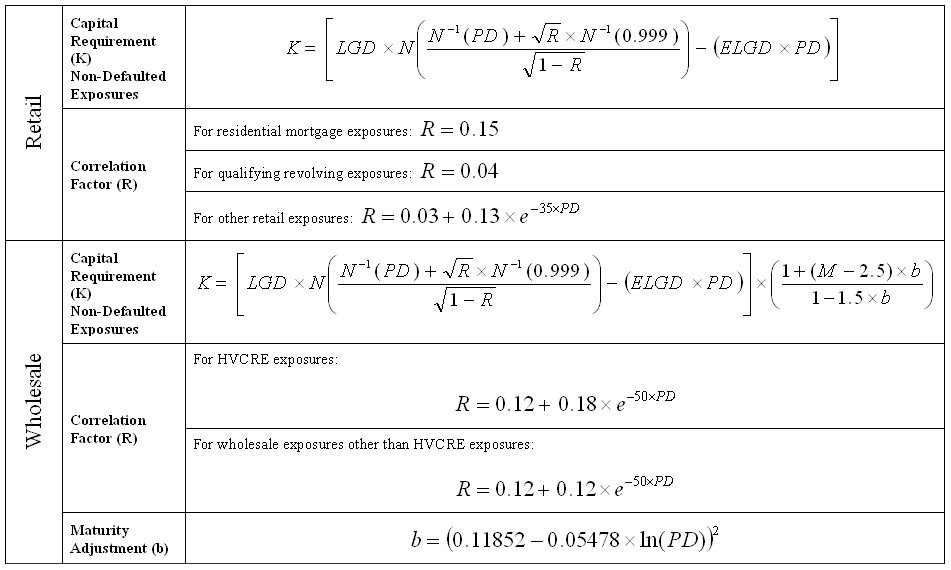

Under the proposed rule, the wholesale and retail risk-weighted assets calculation consists of four phases: (1) categorization of exposures; (2) assignment of wholesale exposures to rating grades and segmentation of retail exposures; (3) assignment of risk parameters to wholesale obligors and exposures and segments of retail exposures; and (4) calculation of risk-weighted asset amounts. Phase 1 involves the categorization of a bank's exposures into four general categories – wholesale exposures, retail exposures, securitization exposures, and equity exposures. Phase 1 also involves the further classification of retail exposures into subcategories and identifying certain wholesale exposures that receive a specific treatment within the wholesale framework. Phase 2 involves the assignment of wholesale obligors and exposures to rating grades and the segmentation of retail exposures. Phase 3 requires the bank to assign a PD, ELGD, LGD, EAD, and M to each wholesale exposure and a PD, ELGD, LGD, and EAD to each segment of retail exposures. In phase 4, the bank calculates the risk-weighted asset amount (i) for each wholesale exposure and segment of retail exposures by inserting the risk parameter estimates into the appropriate IRB risk-based capital formula and multiplying the formula's dollar risk-based capital requirement output by 12.5; and (ii) for on-balance sheet assets that are not included in one of the defined exposure categories and for certain immaterial portfolios of exposures by multiplying the carrying value or notional amount of the exposures by a 100 percent risk weight.

In phase 1, a bank must determine which of its exposures fall into each of the four principal IRB exposure categories – wholesale exposures, retail exposures, securitization exposures, and equity exposures. In addition, a bank must identify within the wholesale exposure category certain exposures that receive a special treatment under the wholesale framework. These exposures include HVCRE exposures, sovereign exposures, eligible purchased wholesale receivables, eligible margin loans, repo-style transactions, OTC derivative contracts, unsettled transactions, and eligible guarantees and eligible credit derivatives that are used as credit risk mitigants.

The treatment of HVCRE exposures and eligible purchased wholesale receivables is discussed below in this section. The treatment of eligible margin loans, repo-style transactions, OTC derivative contracts, and eligible guarantees and eligible credit derivatives that are credit risk mitigants is discussed in section V.C. of the preamble. In addition, sovereign exposures and exposures to or directly and unconditionally guaranteed by the Bank for International Settlements, the International Monetary Fund, the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and multi-lateral development banks45 are exempt from the 0.03 percent floor on PD discussed in the next section.

In phase 1, a bank also must subcategorize its retail exposures as residential mortgage exposures, QREs, or other retail exposures. In addition, a bank must identify any on-balance sheet asset that does not meet the definition of a wholesale, retail, securitization, or equity exposure, as well as any non-material portfolio of exposures to which it chooses, subject to supervisory review, not to apply the IRB risk-based capital formulas.

In phase 2, a bank must assign each wholesale obligor to a single rating grade (for purposes of assigning an estimated PD) and may assign each wholesale exposure to loss severity rating grades (for purposes of assigning an estimated ELGD and LGD). A bank that elects not use a loss severity rating grade system for a wholesale exposure will directly assign ELGD and LGD to the wholesale exposure in phase 3. As a part of the process of assigning wholesale obligors to rating grades, a bank must identify which of its wholesale obligors are in default.

In addition, a bank must divide its retail exposures within each retail subcategory into segments that have homogeneous risk characteristics.46 Segmentation is the grouping of exposures within each subcategory according to the predominant risk characteristics of the borrower (for example, credit score, debt-to-income ratio, and delinquency) and the exposure (for example, product type and LTV ratio). In general, retail segments should not cross national jurisdictions. A bank would have substantial flexibility to use the retail portfolio segmentation it believes is most appropriate for its activities, subject to the following broad principles:

· Differentiation of risk – Segmentation should provide meaningful differentiation of risk. Accordingly, in developing its risk segmentation system, a bank should consider the chosen risk drivers' ability to separate risk consistently over time and the overall robustness of the bank's approach to segmentation.

· Reliable risk characteristics – Segmentation should use borrower-related risk characteristics and exposure-related risk characteristics that reliably and consistently over time differentiate a segment's risk from that of other segments.

· Consistency – Risk drivers for segmentation should be consistent with the predominant risk characteristics used by the bank for internal credit risk measurement and management.

· Accuracy – The segmentation system should generate segments that separate exposures by realized performance and should be designed so that actual long-run outcomes closely approximate the retail risk parameters estimated by the bank.

A bank might choose to segment exposures by common risk drivers that are relevant and material in determining the loss characteristics of a particular retail product. For example, a bank may segment mortgage loans by LTV band, age from origination, geography, origination channel, and credit score. Statistical modeling, expert judgment, or some combination of the two may determine the most relevant risk drivers. Alternatively, a bank might segment by grouping exposures with similar loss characteristics, such as loss rates or default rates, as determined by historical performance of segments with similar risk characteristics.

Banks commonly obtain tranched credit protection, for example first-loss or second-loss guarantees, on certain retail exposures such as residential mortgages. The agencies recognize that the securitization framework, which applies to tranched wholesale exposures, is not appropriate for individual retail exposures. The agencies therefore are proposing to exclude tranched guarantees that apply only to an individual retail exposure from the securitization framework. An important result of this exclusion is that, in contrast to the treatment of wholesale exposures, a bank may recognize recoveries from both an obligor and a guarantor for purposes of estimating the ELGD and LGD for certain retail exposures. Question 29: The agencies seek comment on this approach to tranched guarantees on retail exposures and on alternative approaches that could more appropriately reflect the risk mitigating effect of such guarantees while addressing the agencies' concerns about counterparty credit risk and correlation between the credit quality of an obligor and a guarantor.

Banks have expressed concern about the treatment of retail margin loans under the New Accord. Due to the highly collateralized nature and low loss frequency of margin loans, banks typically collect little customer-specific information that they could use to differentiate margin loans into segments. The agencies believe that a bank could appropriately segment its margin loan portfolio using only product-specific risk drivers, such as product type and origination channel. A bank could then use the retail definition of default to associate a PD, ELGD, and LGD with each segment. As described in section 32 of the proposed rule, a bank could adjust the EAD of eligible margin loans to reflect the risk-mitigating effect of financial collateral. For a segment of retail eligible margin loans, a bank would associate an ELGD and LGD with the segment that do not reflect the presence of collateral. If a bank is not able to estimate PD, ELGD, and LGD for a segment of eligible margin loans, the bank may apply a 300 percent risk weight to the EAD of the segment. Question 30: The agencies seek comment on wholesale and retail exposure types for which banks are not able to calculate PD, ELGD, and LGD and on what an appropriate risk-based capital treatment for such exposures might be.

In phase 3, each retail segment will typically be associated with a separate PD, ELGD, LGD, and EAD. In some cases, it may be reasonable to use the same PD, ELGD, LGD, or EAD estimate for multiple segments.

A bank must segment defaulted retail exposures separately from non-defaulted retail exposures and should base the segmentation of defaulted retail exposures on characteristics that are most predictive of current loss and recovery rates. This segmentation should provide meaningful differentiation so that individual exposures within each defaulted segment do not have material differences in their expected loss severity.

A bank may also elect to use a top-down approach, similar to the treatment of retail exposures, for eligible purchased wholesale receivables. Under this approach, in phase 2, a bank would group its eligible purchased wholesale receivables that, when consolidated by obligor, total less than $1 million into segments that have homogeneous risk characteristics. To be an eligible purchased wholesale receivable, several criteria must be met:

· The purchased wholesale receivable must be purchased from an unaffiliated seller and must not have been directly or indirectly originated by the purchasing bank;

· The purchased wholesale receivable must be generated on an arm's-length basis between the seller and the obligor. Intercompany accounts receivable and receivables subject to contra-accounts between firms that buy and sell to each other are ineligible;

· The purchasing bank must have a claim on all proceeds from the receivable or a pro-rata interest in the proceeds; and

· The purchased wholesale receivable must have an effective remaining maturity of less than one year.

The agencies are proposing a treatment for wholesale lease residuals that differs from the New Accord. A wholesale lease residual typically exposes a bank to the risk of a decline in value of the leased asset and to the credit risk of the lessee. Although the New Accord provides for a flat 100 percent risk weight for wholesale lease residuals, the agencies believe this is excessively punitive for leases to highly creditworthy lessees. Accordingly, the proposed rule would require a bank to treat its net investment in a wholesale lease as a single exposure to the lessee. There would not be a separate capital calculation for the wholesale lease residual. In contrast, a retail lease residual, consistent with the New Accord, would be assigned a risk-weighted asset amount equal to its residual value (as described in more detail above).

In phase 3, a bank would associate a PD with each wholesale obligor rating grade; associate an ELGD or LGD with each wholesale loss severity rating grade or assign an ELGD and LGD to each wholesale exposure; assign an EAD and M to each wholesale exposure; and assign a PD, ELGD, LGD, and EAD to each segment of retail exposures. The quantification phase can generally be divided into four steps—obtaining historical reference data, estimating the risk parameters for the reference data, mapping the historical reference data to the bank's current exposures, and determining the risk parameters for the bank's current exposures.

A bank should base its estimation of the values assigned to PD, ELGD, LGD, and EAD47 on historical reference data that are a reasonable proxy for the bank's current exposures and that provide meaningful predictions of the performance of such exposures. A "reference data set" consists of a set of exposures to defaulted wholesale obligors and defaulted retail exposures (in the case of ELGD, LGD, and EAD estimation) or to both defaulted and non-defaulted wholesale obligors and retail exposures (in the case of PD estimation).

The reference data set should be described using a set of observed characteristics. Relevant characteristics might include debt ratings, financial measures, geographic regions, the economic environment and industry/sector trends during the time period of the reference data, borrower and loan characteristics related to the risk parameters (such as loan terms, LTV ratio, credit score, income, debt-to-income ratio, or performance history), or other factors that are related in some way to the risk parameters. Banks may use more than one reference data set to improve the robustness or accuracy of the parameter estimates.

A bank should then apply statistical techniques to the reference data to determine a relationship between risk characteristics and the estimated risk parameter. The result of this step is a model that ties descriptive characteristics to the risk parameter estimates. In this context, the term 'model' is used in the most general sense; a model may be simple, such as the calculation of averages, or more complicated, such as an approach based on advanced regression techniques. This step may include adjustments for differences between this proposed rule's definition of default and the default definition in the reference data set, or adjustments for data limitations. This step should also include adjustments for seasoning effects related to retail exposures.

A bank may use more than one estimation technique to generate estimates of the risk parameters, especially if there are multiple sets of reference data or multiple sample periods. If multiple estimates are generated, the bank must have a clear and consistent policy on reconciling and combining the different estimates.

Once a bank estimates PD, ELGD, LGD, and EAD for its reference data sets, it would create a link between its portfolio data and the reference data based on corresponding characteristics. Variables or characteristics that are available for the existing portfolio would be mapped or linked to the variables used in the default, loss-severity, or exposure amount model. In order to effectively map the data, reference data characteristics would need to allow for the construction of rating and segmentation criteria that are consistent with those used on the bank's portfolio. An important element of mapping is making adjustments for differences between reference data sets and the bank's exposures.

Finally, a bank would apply the risk parameters estimated for the reference data to the bank's actual portfolio data. The bank would attribute a PD to each wholesale obligor and each segment of retail exposures, and an ELGD, LGD, and EAD to each wholesale exposure and to each segment of retail exposures. If multiple data sets or estimation methods are used, the bank must adopt a means of combining the various estimates at this stage.

The proposed rule, as noted above, permits a bank to elect to segment its eligible purchased wholesale receivables like retail exposures. A bank that chooses to apply this treatment must directly assign a PD, ELGD, LGD, EAD, and M to each such segment. If a bank can estimate ECL (but not PD or LGD) for a segment of eligible purchased wholesale receivables, the bank must assume that the ELGD and LGD of the segment equal 100 percent and that the PD of the segment equals ECL divided by EAD. The bank must estimate ECL for the receivables without regard to any assumption of recourse or guarantees from the seller or other parties. The bank would then use the wholesale exposure formula in section 31(e) of the proposed rule to determine the risk-based capital requirement for each segment of eligible purchased wholesale receivables.

A bank may recognize the credit risk mitigation benefits of collateral that secures a wholesale exposure by adjusting its estimate of the ELGD and LGD of the exposure and may recognize the credit risk mitigation benefits of collateral that secures retail exposures by adjusting its estimate of the PD, ELGD, and LGD of the segment of retail exposures. In certain cases, however, a bank may take financial collateral into account in estimating the EAD of repo-style transactions, eligible margin loans, and OTC derivative contracts (as provided in section 32 of the proposed rule).

The proposed rule also provides that a bank may use an EAD of zero for (i) derivative contracts that are traded on an exchange that requires the daily receipt and payment of cash-variation margin; (ii) derivative contracts and repo-style transactions that are outstanding with a qualifying central counterparty, but not for those transactions that the qualifying central counterparty has rejected; and (iii) credit risk exposures to a qualifying central counterparty that arise from derivative contracts and repo-style transactions in the form of clearing deposits and posted collateral. The proposed rule defines a qualifying central counterparty as a counterparty (for example, a clearing house) that: (i) facilitates trades between counterparties in one or more financial markets by either guaranteeing trades or novating contracts; (ii) requires all participants in its arrangements to be fully collateralized on a daily basis; and (iii) the bank demonstrates to the satisfaction of its primary Federal supervisor is in sound financial condition and is subject to effective oversight by a national supervisory authority.

Some repo-style transactions and OTC derivative contracts giving rise to counterparty credit risk may give rise, from an accounting point of view, to both on- and off-balance sheet exposures. Where a bank is using an EAD approach to measure the amount of risk exposure for such transactions, factoring in collateral effects where applicable, it would not also separately apply a risk-based capital requirement to an on-balance sheet receivable from the counterparty recorded in connection with that transaction. Because any exposure arising from the on-balance sheet receivable is captured in the capital requirement determined under the EAD approach, a separate capital requirement would double count the exposure for regulatory capital purposes.

A bank may take into account the risk reducing effects of eligible guarantees and eligible credit derivatives in support of a wholesale exposure by applying the PD substitution approach or the LGD adjustment approach to the exposure as provided in section 33 of the proposed rule or, if applicable, applying double default treatment to the exposure as provided in section 34 of the proposed rule. A bank may decide separately for each wholesale exposure that qualifies for the double default treatment whether to apply the PD substitution approach, the LGD adjustment approach, or the double default treatment. A bank may take into account the risk reducing effects of guarantees and credit derivatives in support of retail exposures in a segment when quantifying the PD, ELGD, and LGD of the segment.

There are several supervisory limitations imposed on risk parameters assigned to wholesale obligors and exposures and segments of retail exposures. First, the PD for each wholesale obligor or segment of retail exposures may not be less than 0.03 percent, except for exposures to or directly and unconditionally guaranteed by a sovereign entity, the Bank for International Settlements, the International Monetary Fund, the European Commission, the European Central Bank, or a multi-lateral development bank, to which the bank assigns a rating grade associated with a PD of less than 0.03 percent. Second, the LGD of a segment of residential mortgage exposures (other than segments of residential mortgage exposures for which all or substantially all of the principal of the exposures is directly and unconditionally guaranteed by the full faith and credit of a sovereign entity) may not be less than 10 percent. These supervisory floors on PD and LGD apply regardless of whether the bank recognizes an eligible guarantee or eligible credit derivative as provided in sections 33 and 34 of the proposed rule.

The agencies would not allow a bank to artificially group exposures into segments specifically to avoid the LGD floor for mortgage products. A bank should use consistent risk drivers to determine its retail exposure segmentations and not artificially segment low LGD loans with higher LGD loans to avoid the floor.

A bank also must calculate the effective remaining maturity (M) for each wholesale exposure. For wholesale exposures other than repo-style transactions, eligible margin loans, and OTC derivative contracts subject to a qualifying master netting agreement, M would be the weighted-average remaining maturity (measured in whole or fractional years) of the expected contractual cash flows from the exposure, using the undiscounted amounts of the cash flows as weights. A bank may use its best estimate of future interest rates to compute expected contractual interest payments on a floating-rate exposure, but it may not consider expected but noncontractually required returns of principal, when estimating M. A bank could, at its option, use the nominal remaining maturity (measured in whole or fractional years) of the exposure. The M for repo-style transactions, eligible margin loans, and OTC derivative contracts subject to a qualifying master netting agreement would be the weighted-average remaining maturity (measured in whole or fractional years) of the individual transactions subject to the qualifying master netting agreement, with the weight of each individual transaction set equal to the notional amount of the transaction. Question 31: The agencies seek comment on the appropriateness of permitting a bank to consider prepayments when estimating M and on the feasibility and advisability of using discounted (rather than undiscounted) cash flows as the basis for estimating M.

Under the proposed rule, a qualifying master netting agreement is defined to mean any written, legally enforceable bilateral agreement, provided that:

(i) The agreement creates a single legal obligation for all individual transactions covered by the agreement upon an event of default, including bankruptcy, insolvency, or similar proceeding, of the counterparty;

(ii) The agreement provides the bank the right to accelerate, terminate, and close-out on a net basis all transactions under the agreement and to liquidate or set off collateral promptly upon an event of default, including upon an event of bankruptcy, insolvency, or similar proceeding, of the counterparty, provided that, in any such case, any exercise of rights under the agreement will not be stayed or avoided under applicable law in the relevant jurisdictions;

(iii) The bank has conducted and documented sufficient legal review to conclude with a well-founded basis that the agreement meets the requirements of paragraph (ii) of this definition and that in the event of a legal challenge (including one resulting from default or from bankruptcy, insolvency, or similar proceeding) the relevant court and administrative authorities would find the agreement to be legal, valid, binding, and enforceable under the law of the relevant jurisdictions;

(iv) The bank establishes and maintains procedures to monitor possible changes in relevant law and to ensure that the agreement continues to satisfy the requirements of this definition; and

(v) The agreement does not contain a walkaway clause (that is, a provision that permits a non-defaulting counterparty to make lower payments than it would make otherwise under the agreement, or no payment at all, to a defaulter or the estate of a defaulter, even if the defaulter or the estate of the defaulter is a net creditor under the agreement).

The agencies would consider the following jurisdictions to be relevant for a qualifying master netting agreement: the jurisdiction in which each counterparty is chartered or the equivalent location in the case of non-corporate entities, and if a branch of a counterparty is involved, then also the jurisdiction in which the branch is located; the jurisdiction that governs the individual transactions covered by the agreement; and the jurisdiction that governs the agreement.

For most exposures, M may be no greater than five years and no less than one year. For exposures that have an original maturity of less than one year and are not part of a bank's ongoing financing of the obligor, however, a bank may set M equal to the greater of one day and M. An exposure is not part of a bank's ongoing financing of the obligor if the bank (i) has a legal and practical ability not to renew or roll over the exposure in the event of credit deterioration of the obligor; (ii) makes an independent credit decision at the inception of the exposure and at every renewal or rollover; and (iii) has no substantial commercial incentive to continue its credit relationship with the obligor in the event of credit deterioration of the obligor. Examples of transactions that may qualify for the exemption from the one-year maturity floor include due from other banks, including deposits in other banks; bankers' acceptances; sovereign exposures; short-term self-liquidating trade finance exposures; repo-style transactions; eligible margin loans; unsettled trades and other exposures resulting from payment and settlement processes; and collateralized OTC derivative contracts subject to daily remargining.

After a bank assigns risk parameters to each of its wholesale obligors and exposures and retail segments, the bank would calculate the dollar risk-based capital requirement for each wholesale exposure to a non-defaulted obligor or segment of non-defaulted retail exposures (except eligible guarantees and eligible credit derivatives that hedge another wholesale exposure and exposures to which the bank is applying the double default treatment in section 34 of the proposed rule) by inserting the risk parameters for the wholesale obligor and exposure or retail segment into the appropriate IRB risk-based capital formula specified in Table C and multiplying the output of the formula (K) by the EAD of the exposure or segment. Eligible guarantees and eligible credit derivatives that are hedges of a wholesale exposure would be reflected in the risk-weighted assets amount of the hedged exposure (i) through adjustments made to the risk parameters of the hedged exposure under the PD substitution or LGD adjustment approach in section 33 of the proposed rule or (ii) through a separate double default risk-based capital requirement formula in section 34 of the proposed rule.

The sum of the dollar risk-based capital requirements for wholesale exposures to a non-defaulted obligor and segments of non-defaulted retail exposures (including exposures subject to the double default treatment described below) would equal the total dollar risk-based capital requirement for those exposures and segments. The total dollar risk-based capital requirement would be converted into a risk-weighted asset amount by multiplying it by 12.5.

To compute the risk-weighted asset amount for a wholesale exposure to a defaulted obligor, a bank would first have to compare two amounts: (i) the sum of 0.08 multiplied by the EAD of the wholesale exposure plus the amount of any charge-offs or write-downs on the exposure; and (ii) K for the wholesale exposure (as determined in Table C immediately before the obligor became defaulted), multiplied by the EAD of the exposure immediately before the exposure became defaulted. If the amount calculated in (i) is equal to or greater than the amount calculated in (ii), the dollar risk-based capital requirement for the exposure is 0.08 multiplied by the EAD of the exposure. If the amount calculated in (i) is less than the amount calculated in (ii), the dollar risk-based capital requirement for the exposure is K for the exposure (as determined in Table C immediately before the obligor became defaulted), multiplied by the EAD of the exposure. The reason for this comparison is to ensure that a bank does not receive a regulatory capital benefit as a result of the exposure moving from non-defaulted to defaulted status.

The proposed rule provides a simpler approach for segments of defaulted retail exposures. The dollar risk-based capital requirement for a segment of defaulted retail exposures equals 0.08 multiplied by the EAD of the segment. The agencies are proposing this uniform 8 percent risk-based capital requirement for defaulted retail exposures to ease implementation burden on banks and in light of accounting and other supervisory policies in the retail context that would help prevent the sum of a bank's ECL and risk-based capital requirement for a retail exposure from declining at the time of default.

To convert the dollar risk-based capital requirements to a risk-weighted asset amount, the bank would sum the dollar risk-based capital requirements for all wholesale exposures to defaulted obligors and segments of defaulted retail exposures and multiply the sum by 12.5.

A bank could assign a risk-weighted asset amount of zero to cash owned and held in all offices of the bank or in transit, and for gold bullion held in the bank's own vaults or held in another bank's vaults on an allocated basis, to the extent it is offset by gold bullion liabilities. On-balance sheet assets that do not meet the definition of a wholesale, retail, securitization, or equity exposure – for example, property, plant, and equipment and mortgage servicing rights – and portfolios of exposures that the bank has demonstrated to its primary Federal supervisor's satisfaction are, when combined with all other portfolios of exposures that the bank seeks to treat as immaterial for risk-based capital purposes, not material to the bank generally would be assigned risk-weighted asset amounts equal to their carrying value (for on-balance sheet exposures) or notional amount (for off-balance sheet exposures). For this purpose, the notional amount of an OTC derivative contract that is not a credit derivative is the EAD of the derivative as calculated in section 32 of the proposed rule.

Total wholesale and retail risk-weighted assets would be the sum of risk-weighted assets for wholesale exposures to non-defaulted obligors and segments of non-defaulted retail exposures, wholesale exposures to defaulted obligors and segments of defaulted retail exposures, assets not included in an exposure category, non-material portfolios of exposures, and unsettled transactions minus the amounts deducted from capital pursuant to the general risk-based capital rules (excluding those deductions reversed in section 12 of the proposed rule).

The general risk-based capital rules assign 50 and 100 percent risk weights to certain one-to-four family residential pre-sold construction loans and multifamily residential loans.48 The agencies adopted these provisions as a result of the Resolution Trust Corporation Refinancing, Restructuring, and Improvement Act of 1991 (RTCRRI Act).49 The RTCRRI Act mandates that each agency provide in its capital regulations (i) a 50 percent risk weight for certain one-to-four family residential pre-sold construction loans and multifamily residential loans that meet specific statutory criteria set forth in the Act and any other underwriting criteria imposed by the agencies; and (ii) a 100 percent risk weight for one-to-four family residential pre-sold construction loans for residences for which the purchase contract is cancelled.50

When Congress enacted the RTCRRI Act in 1991, the agencies' risk-based capital rules reflected the Basel I framework. Consequently, the risk weight treatment for certain categories of mortgage loans in the RTCRRI Act assumes a risk weight bucketing approach, instead of the more risk-sensitive IRB approach in the Basel II framework.

For purposes of this proposed rule implementing the Basel II IRB approach, the agencies are proposing that the three types of residential mortgage loans addressed by the RTCRRI Act should continue to receive the risk weights provided in the Act. Specifically, consistent with the general risk-based capital rules, the proposed rule requires a bank to use the following risk weights (instead of the risk weights that would otherwise be produced under the IRB risk-based capital formulas): (i) a 50 percent risk weight for one-to-four family residential construction loans if the residences have been pre-sold under firm contracts to purchasers who have obtained firm commitments for permanent qualifying mortgages and have made substantial earnest money deposits, and the loans meet the other underwriting characteristics established by the agencies in the general risk-based capital rules;51 (ii) a 50 percent risk weight for multifamily residential loans that meet certain statutory loan-to-value, debt-to-income, amortization, and performance requirements, and meet the other underwriting characteristics established by the agencies in the general risk-based capital rules;52 and (iii) a 100 percent risk weight for one-to-four family residential pre-sold construction loans for a residence for which the purchase contract is canceled.53 Mortgage loans that do not meet the relevant criteria do not qualify for the statutory risk weights and will be risk-weighted according to the IRB risk-based capital formulas.

The agencies understand that there is a tension between the statutory risk weights provided by the RTCRRI Act and the more risk-sensitive IRB approaches to risk-based capital that are contained in this proposed rule. Question 32: The agencies seek comment on whether the agencies should impose the following underwriting criteria as additional requirements for a Basel II bank to qualify for the statutory 50 percent risk weight for a particular mortgage loan: (i) that the bank has an IRB risk measurement and management system in place that assesses the PD and LGD of prospective residential mortgage exposures; and (ii) that the bank's IRB system generates a 50 percent risk weight for the loan under the IRB risk-based capital formulas. The agencies note that a capital-related provision of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act of 1991 (FDICIA), enacted by Congress just four days after its adoption of the RTCRRI Act, directs each agency to revise its risk-based capital standards for DIs to ensure that those standards "reflect the actual performance and expected risk of loss of multifamily mortgages."54

Question 33: The agencies seek comment on all aspects of the proposed treatment of one-to-four family residential pre-sold construction loans and multifamily residential loans.

Banks use a number of techniques to mitigate credit risk. This section of the preamble describes how the proposed rule recognizes the risk-mitigating effects of both financial collateral (defined below) and nonfinancial collateral, as well as guarantees and credit derivatives, for risk-based capital purposes. To recognize credit risk mitigants for risk-based capital purposes, a bank should have in place operational procedures and risk management processes that ensure that all documentation used in collateralizing or guaranteeing a transaction is legal, valid, binding, and enforceable under applicable law in the relevant jurisdictions. The bank should have conducted sufficient legal review to reach a well-founded conclusion that the documentation meets this standard and should reconduct such a review as necessary to ensure continuing enforceability.

Although the use of CRM techniques may reduce or transfer credit risk, it simultaneously may increase other risks, including operational, liquidity, and market risks. Accordingly, it is imperative that banks employ robust procedures and processes to control risks, including roll-off risk and concentration risk, arising from the bank's use of CRM techniques and to monitor the implications of using CRM techniques for the bank's overall credit risk profile.

Under the proposed rule, a bank generally recognizes collateral that secures a wholesale exposure as part of the ELGD and LGD estimation process and generally recognizes collateral that secures a retail exposure as part of the PD, ELGD, and LGD estimation process, as described above in section V.B.3. of the preamble. However, in certain limited circumstances described in the next section, a bank may adjust EAD to reflect the risk mitigating effect of financial collateral.

When reflecting the credit risk mitigation benefits of collateral in its estimation of the risk parameters of a wholesale or retail exposure, a bank should:

(i) Conduct sufficient legal review to ensure, at inception and on an ongoing basis, that all documentation used in the collateralized transaction is binding on all parties and legally enforceable in all relevant jurisdictions;

(ii) Consider the relation (that is, correlation) between obligor risk and collateral risk in the transaction;

(iii) Consider any currency and/or maturity mismatch between the hedged exposure and the collateral;

(iv) Ground its risk parameter estimates for the transaction in historical data, using historical recovery rates where available; and

(v) Fully take into account the time and cost needed to realize the liquidation proceeds and the potential for a decline in collateral value over this time period.

The bank also should ensure that:

(i) The legal mechanism under which the collateral is pledged or transferred ensures that the bank has the right to liquidate or take legal possession of the collateral in a timely manner in the event of the default, insolvency, or bankruptcy (or other defined credit event) of the obligor and, where applicable, the custodian holding the collateral;

(ii) The bank has taken all steps necessary to fulfill legal requirements to secure its interest in the collateral so that it has and maintains an enforceable security interest;

(iii) The bank has clear and robust procedures for the timely liquidation of collateral to ensure observation of any legal conditions required for declaring the default of the borrower and prompt liquidation of the collateral in the event of default;

(iv) The bank has established procedures and practices for (A) conservatively estimating, on a regular ongoing basis, the market value of the collateral, taking into account factors that could affect that value (for example, the liquidity of the market for the collateral and obsolescence or deterioration of the collateral), and (B) where applicable, periodically verifying the collateral (for example, through physical inspection of collateral such as inventory and equipment); and

(v) The bank has in place systems for promptly requesting and receiving additional collateral for transactions whose terms require maintenance of collateral values at specified thresholds.

This section describes two EAD-based methodologies—a collateral haircut approach and an internal models methodology—that a bank may use instead of an ELGD/LGD estimation methodology to recognize the benefits of financial collateral in mitigating the counterparty credit risk associated with repo-style transactions, eligible margin loans, collateralized OTC derivative contracts, and single product groups of such transactions with a single counterparty subject to a qualifying master netting agreement. A third methodology, the simple VaR methodology, is also available to recognize financial collateral mitigating the counterparty credit risk of single product netting sets of repo-style transactions and eligible margin loans.

A bank may use any combination of the three methodologies for collateral recognition; however, it must use the same methodology for similar exposures. A bank may choose to use one methodology for agency securities lending transactions – that is, repo-style transactions in which the bank, acting as agent for a customer, lends the customer's securities and indemnifies the customer against loss – and another methodology for all other repo-style transactions. This section also describes the methodology for calculating EAD for an OTC derivative contract or set of OTC derivative contracts subject to a qualifying master netting agreement. Table D illustrates which EAD estimation methodologies may be applied to particular types of exposure.

| Models approach | ||||

| Current exposure methodology |

Collateral haircut approach |

Simple VaR55 methodology |

Internal models methodology |

|

| OTC derivative | X | N/A | N/A | X |

| Recognition of collateral for OTC derivatives | N/A | X56 | N/A | X |

| Repo-style transaction | N/A | X | X | X |

| Eligible margin loan | N/A | X | X | X |

| Cross-product netting set | N/A | N/A | N/A | X |

Question 34: For purposes of determining EAD for counterparty credit risk and recognizing collateral mitigating that risk, the proposed rule allows banks to take into account only financial collateral, which, by definition, does not include debt securities that have an external rating lower than one rating category below investment grade. The agencies invite comment on the extent to which lower-rated debt securities or other securities that do not meet the definition of financial collateral are used in these transactions and on the CRM value of such securities.

Under the proposal, a bank could recognize the risk mitigating effect of financial collateral that secures a repo-style transaction, eligible margin loan, or single-product group of such transactions with a single counterparty subject to a qualifying master netting agreement (netting set) through an adjustment to EAD rather than ELGD and LGD. The bank may use a collateral haircut approach or one of two models approaches: a simple VaR methodology (for single-product netting sets of repo-style transactions or eligible margin loans) or an internal models methodology. Figure 2 illustrates the methodologies available for calculating EAD and LGD for eligible margin loans and repo-style transactions.

The proposed rule defines repo-style transaction as a repurchase or reverse repurchase transaction, or a securities borrowing or securities lending transaction (including a transaction in which the bank acts as agent for a customer and indemnifies the customer against loss), provided that:

(i) The transaction is based solely on liquid and readily marketable securities or cash;

(ii) The transaction is marked to market daily and subject to daily margin maintenance requirements;

(iii) The transaction is executed under an agreement that provides the bank the right to accelerate, terminate, and close-out the transaction on a net basis and to liquidate or set off collateral promptly upon an event of default (including upon an event of bankruptcy, insolvency, or similar proceeding) of the counterparty, provided that, in any such case, any exercise of rights under the agreement will not be stayed or avoided under applicable law in the relevant jurisdictions;57 and

(iv) The bank has conducted and documented sufficient legal review to conclude with a well-founded basis that the agreement meets the requirements of paragraph (iii) of this definition and is legal, valid, binding, and enforceable under applicable law in the relevant jurisdictions.

Question 35: The agencies recognize that criterion (iii) above may pose challenges for certain transactions that would not be eligible for certain exemptions from bankruptcy or receivership laws because the counterparty—for example, a sovereign entity or a pension fund—is not subject to such laws. The agencies seek comment on ways this criterion could be crafted to accommodate such transactions when justified on prudential grounds, while ensuring that the requirements in criterion (iii) are met for transactions that are eligible for those exemptions.

The proposed rule defines an eligible margin loan as an extension of credit where:

(i) The credit extension is collateralized exclusively by debt or equity securities that are liquid and readily marketable;

(ii) The collateral is marked to market daily and the transaction is subject to daily margin maintenance requirements;

(iii) The extension of credit is conducted under an agreement that provides the bank the right to accelerate and terminate the extension of credit and to liquidate or set off collateral promptly upon an event of default (including upon an event of bankruptcy, insolvency, or similar proceeding) of the counterparty, provided that, in any such case, any exercise of rights under the agreement will not be stayed or avoided under applicable law in the relevant jurisdictions;58 and

(iv) The bank has conducted and documented sufficient legal review to conclude with a well-founded basis that the agreement meets the requirements of paragraph (iii) of this definition and is legal, valid, binding, and enforceable under applicable law in the relevant jurisdictions.

The proposed rule describes various ways that a bank may recognize the risk mitigating impact of financial collateral. The proposed rule defines financial collateral as collateral in the form of any of the following instruments in which the bank has a perfected, first priority security interest or the legal equivalent thereof: (i) cash on deposit with the bank (including cash held for the bank by a third-party custodian or trustee); (ii) gold bullion; (iii) long-term debt securities that have an applicable external rating of one category below investment grade or higher (for example, at least BB-); (iv) short-term debt instruments that have an applicable external rating of at least investment grade (for example, at least A-3); (v) equity securities that are publicly traded; (vi) convertible bonds that are publicly traded; and (vii) mutual fund shares for which a share price is publicly quoted daily and money market mutual fund shares. Question 36: The agencies seek comment on the appropriateness of requiring that a bank have a perfected, first priority security interest, or the legal equivalent thereof, in the definition of financial collateral.

The proposed rule defines an external rating as a credit rating assigned by a nationally recognized statistical rating organization (NRSRO) to an exposure that fully reflects the entire amount of credit risk the holder of the exposure has with regard to all payments owed to it under the exposure. For example, if a holder is owed principal and interest on an exposure, the external rating must fully reflect the credit risk associated with timely repayment of principal and interest. Moreover, the external rating must be published in an accessible form and must be included in the transition matrices made publicly available by the NRSRO that summarize the historical performance of positions it has rated.59 Under the proposed rule, an exposure's applicable external rating is the lowest external rating assigned to the exposure by any NRSRO.

Under the collateral haircut approach, a bank would set EAD equal to the sum of three quantities: (i) the value of the exposure less the value of the collateral; (ii) the absolute value of the net position in a given security (where the net position in a given security equals the sum of the current market values of the particular security the bank has lent, sold subject to repurchase, or posted as collateral to the counterparty minus the sum of the current market values of that same security the bank has borrowed, purchased subject to resale, or taken as collateral from the counterparty) multiplied by the market price volatility haircut appropriate to that security; and (iii) the sum of the absolute values of the net position of both cash and securities in each currency that is different from the settlement currency multiplied by the haircut appropriate to each currency mismatch. To determine the appropriate haircuts, a bank could choose to use standard supervisory haircuts or its own estimates of haircuts. For purposes of the collateral haircut approach, a given security would include, for example, all securities with a single Committee on Uniform Securities Identification Procedures (CUSIP) number and would not include securities with different CUSIP numbers, even if issued by the same issuer with the same maturity date. Question 37: The agencies recognize that this is a conservative approach and seek comment on other approaches to consider in determining a given security for purposes of the collateral haircut approach.

If a bank chooses to use standard supervisory haircuts, it would use an 8 percent haircut for each currency mismatch and the haircut appropriate to each security in table E below. These haircuts are based on the 10-business-day holding period for eligible margin loans and may be multiplied by the square root of ½ to convert the standard supervisory haircuts to the 5-business-day minimum holding period for repo-style transactions. A bank must adjust the standard supervisory haircuts upward on the basis of a holding period longer than 10 business days for eligible margin loans or 5 business days for repo-style transactions where and as appropriate to take into account the illiquidity of an instrument.

| Applicable external rating grade category for debt securities | Residual maturity for debt securities | Issuers exempt from the 3 b.p. floor | Other issuers |

| Two highest investment grade rating categories for long-term ratings/highest investment grade rating category for short-term ratings | ≤ 1 year | .005 | .01 |

| > 1 year, ≤ 5 years | .02 | .04 | |

| > 5 years | .04 | .08 | |

| Two lowest investment grade rating categories for both short- and long-term ratings | ≤ 1 year | .01 | .02 |

| > 1 year, ≤ 5 years | .03 | .06 | |

| > 5 years | .06 | .12 | |

| One rating category below investment grade | All | .15 | .25 |

| Main index equities60 (including convertible bonds) and gold | .15 | ||

| Other publicly traded equities (including convertible bonds) | .25 | ||

| Mutual funds | Highest haircut applicable to any security in which the fund can invest | ||

| Cash on deposit with the bank (including a certificate of deposit issued by the bank) | 0 | ||

As an example, assume a bank that uses standard supervisory haircuts has extended an eligible margin loan of $100 that is collateralized by 5-year U.S. Treasury notes with a market value of $100. The value of the exposure less the value of the collateral would be zero, and the net position in the security ($100) times the supervisory haircut (.02) would be $2. There is no currency mismatch. Therefore, the EAD of the exposure would be $0 + $2 = $2.

With the prior written approval of the bank's primary Federal supervisor, a bank may calculate security type and currency mismatch haircuts using its own internal estimates of market price volatility and foreign exchange volatility. The bank's primary Federal supervisor would base approval to use internally estimated haircuts on the satisfaction of certain minimum qualitative and quantitative standards. These standards include: (i) the bank must use a 99th percentile one-tailed confidence interval and a minimum 5-business-day holding period for repo-style transactions and a minimum 10-business-day holding period for all other transactions; (ii) the bank must adjust holding periods upward where and as appropriate to take into account the illiquidity of an instrument; (iii) the bank must select a historical observation period for calculating haircuts of at least one year; and (iv) the bank must update its data sets and recompute haircuts no less frequently than quarterly and must update its data sets and recompute haircuts whenever market prices change materially. A bank must estimate individually the volatilities of the exposure, the collateral, and foreign exchange rates, and may not take into account the correlations between them.

A bank that uses internally estimated haircuts would have to adhere to the following rules. The bank may calculate internally estimated haircuts for categories of debt securities that have an applicable external rating of at least investment grade. The haircut for a category of securities would have to be representative of the internal volatility estimates for securities in that category that the bank has actually lent, sold subject to repurchase, posted as collateral, borrowed, purchased subject to resale, or taken as collateral. In determining relevant categories, the bank would have to take into account (i) the type of issuer of the security; (ii) the applicable external rating of the security; (iii) the maturity of the security; and (iv) the interest rate sensitivity of the security. A bank would calculate a separate internally estimated haircut for each individual debt security that has an applicable external rating below investment grade and for each individual equity security. In addition, a bank would internally estimate a separate currency mismatch haircut for each individual mismatch between each net position in a currency that is different from the settlement currency.

When a bank calculates an internally estimated haircut on a TN-day holding period, which is different from the minimum holding period for the transaction type, the applicable haircut (HM) must be calculated using the following square root of time formula:

(i) TM = 5 for repo-style transactions and 10 for eligible margin loans;

(ii) TN = holding period used by the bank to derive HN; and

(iii) HN = haircut based on the holding period TN.

As noted above, a bank may use one of two internal models approaches to recognize the risk mitigating effects of financial collateral that secures a repo-style transaction or eligible margin loan. This section of the preamble describes the simple VaR methodology; a later section of the preamble describes the internal models methodology (which also may be used to determine the EAD for OTC derivative contracts).

With the prior written approval of its primary Federal supervisor, a bank may estimate EAD for repo-style transactions and eligible margin loans subject to a single product qualifying master netting agreement using a VaR model. Under the simple VaR methodology, a bank's EAD for the transactions subject to such a netting agreement would be equal to the value of the exposures minus the value of the collateral plus a VaR-based estimate of the potential future exposure (PFE), that is, the maximum exposure expected to occur on a future date with a high level of confidence. The value of the exposures is the sum of the current market values of all securities and cash the bank has lent, sold subject to repurchase, or posted as collateral to a counterparty under the netting set. The value of the collateral is the sum of the current market values of all securities and cash the bank has borrowed, purchased subject to resale, or taken as collateral from a counterparty under the netting set.

The VaR model must estimate the bank's 99th percentile, one-tailed confidence interval for an increase in the value of the exposures minus the value of the collateral (ΣE − ΣC) over a 5-business-day holding period for repo-style transactions or over a 10-business-day holding period for eligible margin loans using a minimum one-year historical observation period of price data representing the instruments that the bank has lent, sold subject to repurchase, posted as collateral, borrowed, purchased subject to resale, or taken as collateral.

The qualifying requirements for the use of a VaR model are less stringent than the qualification requirements for the internal models methodology described below. The main ongoing qualification requirement for using a VaR model is that the bank must validate its VaR model by establishing and maintaining a rigorous and regular backtesting regime.

A bank may use either the current exposure methodology or the internal models methodology to determine the EAD for OTC derivative contracts. An OTC derivative contract is defined as a derivative contract that is not traded on an exchange that requires the daily receipt and payment of cash-variation margin. A derivative contract is defined to include interest rate derivative contracts, exchange rate derivative contracts, equity derivative contracts, commodity derivative contracts, credit derivatives, and any other instrument that poses similar counterparty credit risks. The proposed rule also would define derivative contracts to include unsettled securities, commodities, and foreign exchange trades with a contractual settlement or delivery lag that is longer than the normal settlement period (which the proposed rule defines as the lesser of the market standard for the particular instrument or 5 business days). This would include, for example, agency mortgage-backed securities transactions conducted in the To-Be-Announced market.

The proposed current exposure methodology for determining EAD for single OTC derivative contracts is similar to the methodology in the general risk-based capital rules, in that the EAD for an OTC derivative contract would be equal to the sum of the bank's current credit exposure and PFE on the derivative contract. The current credit exposure for a single OTC derivative contract is the greater of the mark-to-market value of the derivative contract or zero.

The proposed current exposure methodology for OTC derivative contracts subject to master netting agreements is also similar to the treatment set forth in the agencies' general risk-based capital rules. Banks would need to calculate net current exposure and adjust the gross PFE using a formula that includes the net to gross current exposure ratio. Moreover, under the agencies' general risk-based capital rules, a bank may not recognize netting agreements for OTC derivative contracts for capital purposes unless it obtains a written and reasoned legal opinion representing that, in the event of a legal challenge, the bank's exposure would be found to be the net amount in the relevant jurisdictions. The agencies are proposing to retain this standard for netting agreements covering OTC derivative contracts. While the legal enforceability of contracts is necessary for a bank to recognize netting effects in the capital calculation, there may be ways other than obtaining an explicit written opinion to ensure the enforceability of a contract. For example, the use of industry developed standardized contracts for certain OTC products and reliance on commissioned legal opinions as to the enforceability of these contracts in many jurisdictions may be sufficient. Question 38: The agencies seek comment on methods banks would use to ensure enforceability of single product OTC derivative netting agreements in the absence of an explicit written legal opinion requirement.