CCAR and Stress Testing as Complementary Supervisory Tools

Tim P. Clark and Lisa H. Ryu1

Federal Reserve Board

1. Introduction

The financial crisis of 2007–09 highlighted a number of deficiencies in the risk measurement and management practices and in the financial resiliency of large, systemically important financial institutions. Of particular importance was the lack of attention that had been paid to low-probability, high-impact events that could strain a firm's capital adequacy, test its ongoing viability, and quickly spread to other financial institutions. Indeed, the continuation of capital distributions at many large bank holding companies (BHCs) well after it became apparent that there was substantial deterioration in the operating environment highlights the extent to which supervisors and management of these companies underestimated the effect that stressed conditions could have on the BHCs' financial soundness. In short, the crisis made clear the need for more robust supervisory and internal capital adequacy assessment processes at BHCs that incorporate a comprehensive, forward-looking assessment of capital adequacy under a variety of stressful scenarios, as well as the need for better firm-wide risk identification and measurement practices to support this analysis.

The annual stress tests conducted by the Federal Reserve (supervisory stress test) and the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) were designed as complementary programs to strengthen both supervisory assessments of capital adequacy and the processes through which large, complex BHCs internally assess their capital needs. These programs focus on BHCs' ability to absorb substantial unexpected losses, while also experiencing significant declines in revenue, and to continue to function as credit intermediaries in a highly stressful environment. By ensuring that the largest BHCs each have sufficient capital to withstand significant stress and continue to operate, these programs can also help the Federal Reserve meet its macroprudential supervisory objective of ensuring that the financial system as a whole can continue to function under adverse conditions. Greater confidence in the largest banks' capacity to withstand stress and continue to operate and lend may well mitigate the extent of an economic downturn.

Supervisory stress tests provide the Federal Reserve with a concurrent, forward-looking assessment of capital adequacy across large, complex BHCs, using a common set of scenarios, models, and assumptions to support comparability. CCAR is a broader supervisory program that includes supervisory stress testing, but that also assesses a BHCs' own practices for determining capital needs, including their practices around risk measurement and management, and capital planning and decisionmaking, as well as internal controls and governance around these practices. Together, these two programs allow supervisors to move beyond more traditional static analysis of capital ratios and to conduct a forward‐looking evaluation of capital adequacy that incorporates both quantitative analysis and qualitative reviews of large BHCs' capital planning and positions.

The remainder of this chapter is organized as follows. First, we will briefly describe the evolution of stress testing and related supervisory capital assessment programs since the Supervisory Capital Assessment Program (SCAP) in 2009. Second, we will discuss key features of and considerations for supervisory stress tests. Third, we will briefly discuss how supervisors assess BHC stress tests and capital planning in CCAR.2 Fourth, we will focus on the role of public disclosure--a key feature of supervisory stress tests and CCAR. Finally, we conclude the chapter with some additional thoughts about the role of CCAR.

2. CCAR and Stress Testing: How did we get here?

a. SCAP – The Beginning

Although both supervisors and financial institutions conducted various forms of stress testing prior to the crisis, the genesis of the current supervisory stress tests and CCAR dates back to early 2009, when supervisors conducted simultaneous stress tests of the 19 largest U.S. BHCs (the Supervisory Capital Assessment Program or SCAP) in the midst of the financial crisis. At the time of the SCAP, the 19 BHCs faced unprecedented deterioration in economic and financial market conditions and the medium-term outlook remained highly uncertain. Investor confidence in the financial health of the banking system was low and negative sentiment was exacerbated by the uncertain outlook. Concerns about the fundamental value of loans and securities held on the BHCs' balance sheet and the effect of market illiquidity and volatility on asset valuations led to widespread uncertainty about the solvency of large BHCs as a group.

The SCAP sought to address this uncertainty by quantifying the potential effect on capital of further deterioration in the economic environment--to a level that was unprecedented post World War II. Specifically, the SCAP stress test assessed potential losses and capital shortfalls at the 19 large BHCs under a uniform scenario that was, by design, even more severe than the expected outcome at that time. The design of the SCAP stress test partly reflects a view that ensuring that large BHCs have sufficient capital to weather a worse-than-expected outcome could mitigate the propagation of adverse shocks to the financial markets and the economy as a whole. The SCAP used a wide range of inputs, including the BHCs' own estimates, supervisory model outputs, data collected from banks, and supervisory judgment to produce estimates of losses, revenues, and capital levels.3

Importantly, the SCAP assessed whether a BHC had sufficient capital to absorb losses and to continue to operate as a financial intermediary by requiring BHCs to meet a post-stress tier 1 common equity ratio of 4 percent and a tier 1 risk-based capital ratio of 6 percent.4 BHCs that fell below this capital ratio target were given one month to develop a detailed capital plan and six months to raise the necessary capital to meet the target. In addition, the U.S. Treasury Department provided a capital backstop in the event any of the 19 BHCs that were found to be in need of capital (that is, had post-stress tier 1 common equity ratios below 4 percent or tier 1 risk-based capital ratios below 6 percent) under the SCAP were unable to raise that equity in private markets. Notably, while 10 out of 19 BHCs that participated in the SCAP failed to meet the post-stress capital target, almost all BHCs with projected capital shortfalls were able to privately raise sufficient equity after the public release of the SCAP results.5

By most assessments, the SCAP was a significant contributor to the stabilization of the financial system.6 While the Treasury backstop was undoubtedly an important element in the SCAP's success, the credibility of the stress test and the public disclosure of its results were also significant contributing factors. The stress tests conducted under the SCAP tested the capital adequacy of the 19 BHCs in a meaningful way--using a severe scenario that yielded estimates of significant potential losses and declining revenues, and a substantial reduction in capital--which supported the perceived credibility of the exercise. In addition, supervisors released bank-by-bank results, the first time such a public disclosure of supervisory information was made. The public disclosure, which included projected losses by asset type and capital shortfalls relative to the post-stress target, reduced the information asymmetry between the market participants and BHCs. Overall, the combination of the widely perceived credibility of the SCAP stress test and the public disclosure of the results helped reduce uncertainty about the financial health of the large BHCs and restored confidence in the U.S. banking system.

b. CCAR and Dodd-Frank Act Stress Tests

Building on the lessons learned from the SCAP, the Federal Reserve initiated CCAR in late 2010 to assess the capital adequacy and the internal capital planning processes of large, complex BHCs and to explicitly and permanently incorporate the forward-looking capital assessment provided by stress testing into the supervisory evaluation of capital adequacy. Initially, the CCAR program covered the same 19 BHCs that participated in the SCAP.7 In November 2011, the Board of Governors issued a rule that requires all U.S. BHCs with total consolidated assets of $50 billion or more to submit annual capital plans to the Federal Reserve and to allow the Federal Reserve to assess whether the plans are supported by robust, forward-looking capital planning processes and whether they have sufficient capital to continue operations throughout times of economic and financial stress.8 Subsequently, BHCs that met the $50 billion asset threshold of the rule, but had not been part of the SCAP, submitted their capital plans under the capital plan rule; however, their capital plans were assessed under the Capital Plan Review (CapPR), not CCAR, consistent with phasing-in of CCAR expectations. Beginning in 2014, all 30 BHCs with total consolidated assets greater than $50 billion will be part of CCAR.

In addition, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (Dodd-Frank Act) required the Federal Reserve to conduct annual supervisory stress tests under three scenarios--baseline, adverse, and severely adverse--and to publicly disclose the results of the stress tests. While the frequency, timing, and supervisory expectations vary depending on each company's size and complexity, the Dodd-Frank Act also requires all federally regulated financial companies with $10 billion or more in total consolidated assets to conduct their own internal stress tests each year and to publicly disclose the results of these internal stress tests under the severely adverse scenario.9

Under CCAR, the post-stress capital ratios are calculated using the capital actions10 in the BHCs' capital plans while supervisory stress tests conducted under the Dodd-Frank Act use stylized assumptions required in the stress testing rules to calculate the post-stress capital ratios. The Federal Reserve's Dodd-Frank Act stress test rule assumes that no future capital action that may be subject to future adjustment, market conditions, or other regulatory approvals will be reflected in a company's projected regulatory capital. As a result, supervisory stress tests conducted under the Dodd-Frank Act incorporate a standardized set of capital action assumptions: continuation of the previous year's level of dividends, no repurchases, or issuances.11 By comparison, post-stress capital ratios for CCAR incorporate the BHCs' planned capital actions over the nine-quarter planning horizon under their baseline scenario. The inclusion of the baseline planned capital actions tests whether the BHCs would remain above the minimum post-stress supervisory targets even if they maintained their planned capital actions and the stressful conditions were realized.

Public disclosure continues to be an important feature of stress testing, and of CCAR. In the spring of 2013, the Federal Reserve published the results of its supervisory stress tests under the severely adverse scenario conducted under the Dodd Frank Act for 18 BHCs.12 Around that time, the same 18 BHCs disclosed the results of their own stress tests conducted under the Dodd-Frank Act severely adverse scenario. In addition, the Federal Reserve published the post-stress capital ratios under CCAR, and for the first time disclosed the decision (and the basis for the decision; qualitative or quantitative) to object or not object to a BHC's capital plan.13

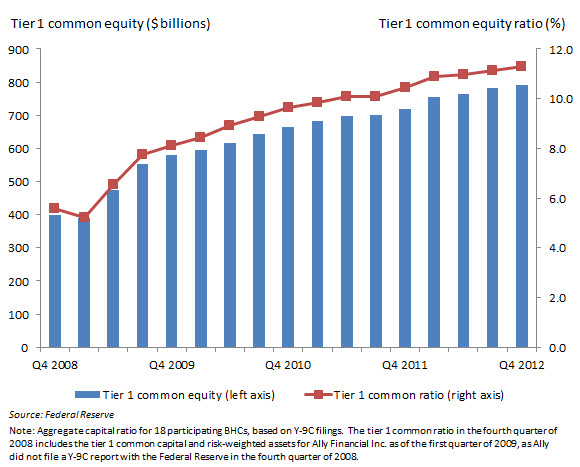

Since the SCAP, stress testing and supervisory programs such as CCAR have been credited with promoting significant capital accretion among large, complex BHCs in the United States. Notably, the aggregate tier 1 common equity ratio of the 18 BHCs that have participated in CCAR through 2013 has more than doubled in the nearly five years since year-end 2008, from 5.6 percent to 11.3 percent, a net gain of about $400 billion of tier 1 common equity in absolute terms (see figure 1). In addition, CCAR is leading to improvements in risk measurement and capital planning practices across the firms.

Figure 1: Aggregate tier 1 common equity ratio for 18 BHCs that participated in CCAR between 2008 and 2012

3. Key Features and Considerations for Supervisory Stress Tests

The Federal Reserve conducts concurrent supervisory stress tests for all large BHCs, based on the same set of scenarios and models, providing a comparable view of capital adequacy across large BHCs. The concurrent nature of the supervisory stress tests and CCAR allows the Federal Reserve to take a cross-BHC perspective and an aggregate industry perspective across time in its assessment, serving both microprudential and macroprudential objectives. While some of the key elements of the supervisory stress tests--including a common set of scenarios, concurrent stress testing of a large share of the U.S. banking system, and public disclosure of bank-by-bank results--have not changed since the SCAP, there has been significant evolution in the models used to support supervisory stress tests, in large part due to new data collections that support supervisory loss and revenue estimation techniques.

Currently, supervisory stress tests use extensive data collected at regular intervals from the BHCs through regulatory reports. While there will always be information asymmetry between the regulators and the BHCs, the data collection that was formalized in late 2011 helped fill the information gap and enhance supervisors' understanding of the BHCs' portfolio risks and the sensitivity of revenues to stress scenarios. In addition, the data collection created strong incentives for large BHCs to develop internal processes that allow for better aggregation across different systems and to provide very detailed data about their borrowers, positions, and sources of revenue. A positive byproduct of the supervisory stress test has been enhancements in the data BHCs themselves now have available for use in their risk measurement and capital planning.

In part due to the detailed data that are now available, supervisory models have become both more independent and more sophisticated, allowing the Federal Reserve to project revenue, expenses, and losses using the data provided by the BHCs, without relying on BHC estimates. In contrast, as mentioned above, the final supervisory estimates produced in SCAP represented a triangulation of a range of inputs, including BHCs' own estimates, supervisory model outputs, data collected from banks, and supervisory judgment. Supervisory models based on more granular BHC-reported data have allowed supervisors to better control the underlying characteristics of each BHC's borrowers and portfolios, and to better incorporate nonlinearity in loss or revenue estimates under stress. The increasing independence of the supervisory models not only further enhances the comparability of results across BHCs, but also supports the credibility of the results.

While the supervisory stress scenarios contain severe stresses that would likely affect BHCs broadly, they are not meant to provide an all-encompassing assessment of the potential stress events or risks each BHC faces. Rather, supervisory scenarios are designed to identify and stress vulnerabilities to common risk factors across BHCs, even if these scenarios may not necessarily be the most severe scenarios for each individual BHC. Supervisory scenarios designed to capture common risks across BHCs should be viewed as a complement to BHC-designed scenarios that explicitly consider BHCs' idiosyncratic risks and vulnerabilities, and which are reviewed and assessed by supervisors during CCAR.

Finally, supervisory stress tests and the models used to support stress testing will likely evolve further over time as BHCs' risk characteristics and business models evolve, the relationship between scenario variables and BHC performance shifts, and the economic and market environment in which BHCs operate changes. In order for supervisory stress tests to remain focused on key vulnerabilities facing the banking system, supervisors will need to update their understanding of the potential risks embedded in new products and businesses and of how emerging risks may affect BHCs' portfolios and businesses--particularly under stress scenarios--through broad supervisory efforts and ongoing research, and incorporate those risks into supervisory stress tests.

4. Assessment of BHC Stress Tests and Capital Planning in CCAR

CCAR is a comprehensive supervisory program that assesses--quantitatively and qualitatively--both BHCs' capital adequacy under stressful scenarios and their capital planning processes. BHCs' internal stress tests, based on the scenarios developed for those stress tests, are key components of their capital planning processes, which should reflect the BHC's views of their own risks and capital needs. In addition to its use as a tool for the supervisory evaluation of capital adequacy at BHCs, other key objectives of CCAR include promoting better identification, measurement, and management of risk at the largest BHCs; fostering greater consideration among boards of directors and senior management at BHCs of potential "tail risk" when assessing their capital needs; and enhancing the corporate governance around BHCs' internal assessments of capital needs and capital distribution decisionmaking. While these objectives are similar to more traditional supervision program elements, they differ in their focus on forward-looking stress analysis in the capital planning process. For example, with CCAR, supervisors expect the BHCs to identify, measure, and capture their risk exposures, and also to consider how risks may emerge and grow under stress. In addition, supervisors also expect key decisionmakers within each BHC to consider a variety of stress scenarios in the analysis supporting their assessments of capital needs and capital distribution decisionmaking.

While supervisory and company-run stress tests provide the forward-looking quantitative assessment of capital adequacy under stress scenarios, qualitative assessments focus on the BHC's processes around internal capital planning, including BHCs' own scenarios. For CCAR, each BHC must submit internal stress test results based on baseline and stress scenarios it develops (BHC scenarios), in addition to three supervisory scenarios. These BHC scenarios are expected to capture BHC-specific, idiosyncratic risks, in addition to a broad macroeconomic downturn that characterizes the supervisory scenarios. The qualitative assessment covers a broad array of supervisory expectations around risk-identification, risk-measurement, and risk-management practices that BHCs use to support their capital planning and internal stress tests, including practices used to estimate stressed net revenue and stressed losses, and the governance and controls around these practices.14

Supervisors expect that that each BHC's internal stress testing framework and capital planning process considers how it would fare under a range of stress scenarios, including those defined by bank-specific idiosyncratic elements. While robust stress testing models should have some basic features, such as sensitivity to macroeconomic conditions and underlying risk characteristics in BHCs' portfolios, there are many possible ways to model revenues and losses under stress scenarios. As noted by a number of observers, to avoid the danger of a "model monoculture,"15 it is important to ensure that BHCs develop internal models that best capture their own risks, rather than relying on models that closely mirror supervisory models.

5. Public Disclosure of Results and Methodologies

As noted earlier, the Federal Reserve first published the bank-by-bank results of its stress tests following the SCAP, and since then, has continued to expand public disclosure around supervisory stress tests and CCAR, with the release of more detailed stress test results and views on BHCs' capital planning processes. The public disclosure provides significant information about the financial health of large BHCs, and improves the transparency of supervisory assessments of the capital adequacy of these firms.

The Federal Reserve has also disclosed an overview of the models used to conduct supervisory stress tests. The overview of supervisory models published in the spring of 2012 and 2013 was comprehensive, but stopped short of revealing the exact specifications of the models or parameter estimates in order to reduce the risk of model convergence.16 Many in the industry have called for greater transparency into the Federal Reserve's models and have criticized the supervisory stress test for being a "black box." Indeed, in evaluating the optimal level of model disclosure, supervisors balanced the need for supervisory transparency against a potential for negative unintended consequences, such as model convergence or a shift in business activity to areas where risks were not as well captured by the stress testing models. The public disclosure of the qualitative assessment of a BHC's capital plan, which also covers its risk identification, stress testing, and capital planning processes, should shift the focus away from supervisory models and estimates over time, and help mitigate concerns about model convergence.

However, some observers continue to express concerns about the extent of current stress test and CCAR disclosure, particularly as the stress testing becomes an annual exercise, arguing that the bank-level disclosure may damage market discipline. They argue, for example, that bank-by-bank disclosure of results may diminish the usefulness of market prices if it creates a disincentive for investors to obtain and produce private information about the banks.17 They also argue that bank-level disclosures could introduce an incentive for banks to reallocate their portfolios solely to avoid "failing" supervisory stress tests and receiving an objection to their capital plan.

Given a widely held view among supervisors and most third-party observers that the public disclosure of stress testing results enhances available information and supports market discipline, it will continue and it is perhaps even likely to be expanded over time. This disclosure provides more information for investors and other market participants than was previously available. Disclosure of bank-by-bank supervisory stress test results, combined with disclosure by each BHC of its results, under the same severely adverse scenario, also provides an unprecedented comparative view of the largest BHCs' financial strength across the banking system. It is important to note, however, that while providing valuable information to market participants, supervisory stress testing results that are disclosed annually are not meant to be a substitute for market prices, or for other privately developed information about the strength and performance of BHCs, that are available at a much higher frequency. Rather, the information this disclosure provides should be seen as complementary to these other sources. Given the breadth of information market participants typically utilize in analyzing large BHCs, it is difficult to envision that the generation of other information critical for market participants in conducting their business each day would be reduced simply because of the annual disclosure of stress testing results. In addition, it is unclear how less disclosure would help reduce, in any meaningful way, a BHC's incentive to reallocate assets in response to a regulatory framework that is being used to assess its capital adequacy. Indeed, given the reality of minimum regulatory capital requirements, such incentives have always existed and would exist irrespective of public disclosure of stress test results. Concerns about the potential reallocation of portfolios with no corresponding reduction in underlying risks are addressed within the context of ongoing supervision and supervisory assessments in CCAR of BHC scenarios, models, and the comprehensiveness of BHCs' risk capture in their internal capital planning processes. Finally, disclosing aggregate but not bank-specific results could be viewed as masking important information about specific banks, undermining the credibility of the supervisory stress tests and potentially creating or exacerbating market uncertainties.

It is also important to note that publishing stress testing information promotes high-quality supervision, as the disclosure serves as a commitment device and holds supervisors accountable. In the SCAP, the disclosure of capital shortfalls clearly held supervisors accountable for producing sound stress test results and following through to ensure banks raised the necessary capital. The annual CCAR disclosure reinforces supervisory accountability for similar reasons. The minimum supervisory post-stress capital targets are set clearly: BHCs must meet all minimum regulatory capital ratios that will be applicable over the stress test planning horizon,18 and a 5 percent tier 1 common equity ratio, all post-stress. The implications of falling below those targets or of having capital planning practices that do not meet supervisory expectations are also clear.

Perhaps rather than limiting disclosure, the more relevant response to concerns about supervisory disclosure is to ensure that scenarios and supervisory models do not remain static over time and to balance the need for transparency of supervisory models against the need to create an incentive for banks to create their own models and to appropriately manage their portfolio risks. For these reasons, the Federal Reserve places additional focus on BHCs' internal processes for stress testing and capital planning, publicly noting the instances where capital plans were objected for qualitative reasons. The disclosure of BHCs' supervisory stress tests, qualitative assessment of their capital planning process, and the disclosure of their own stress tests, collectively, should help ease information asymmetry and reduce the potential for creating negative incentives.

6. Conclusion

Stress testing and the related supervisory expectations for capital planning have fundamentally changed the way the capital adequacy of large, complex BHCs are assessed by both supervisors and the BHCs. BHCs now consider post-stress capital ratios, in addition to current capital ratios, when making decisions around capital allocation and capital actions. As a result, many view CCAR as an alternative measure of a capital buffer above the regulatory minimum, one that in some cases may be more binding than the buffers that already exist in point-in-time regulatory capital requirements.

Based on this view, some argue for full transparency and greater consistency over time both in supervisory scenarios and supervisory models used to support stress testing and CCAR to provide greater certainty of the outcome. While some consistency over time may be desirable, moving toward a more formulaic or rule-based approach that remains mostly unchanged over time would undermine the main strength of stress testing--namely, the flexibility to adapt over time to shifting economic environments, business models and products, and risk-taking behaviors. As a result, stress tests should be best viewed as a complement to, and not a substitute for, regulatory capital requirements that assess BHCs' capital adequacy at a given point in time. Given the inherent uncertainty about the environment in which BHCs operate, stress testing should also incorporate such uncertainty.

In the near future and as a result of the Dodd-Frank Act, regulatory changes will expand the scope of stress testing in the Federal Reserve's supervision of large financial institutions. In addition to large BHCs, stress testing will be used to assess the capital adequacy of systemically important nonbank financial institutions with business models and risk profiles that are materially different from BHCs. Under the proposed rule for large foreign banking organizations operating in the United States, stress testing would also expand to U.S. intermediate holding companies.19 The expansion of the universe of companies that are subject to stress testing will present new challenges and new opportunities to test the strength of key participants in the financial system under stress.

Over time, the Federal Reserve's stress testing and CCAR programs will likely continue to evolve along with economic conditions and the risk profiles and business practices of large financial institutions. Nevertheless, forward-looking assessments of capital adequacy, supported by strong risk measurement and management, stress testing, and the internal controls and governance processes needed to ensure their integrity will likely remain the core element of supervisory expectations around capital planning.

1. The opinions expressed in this chapter are views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Federal Reserve Board or the Federal Reserve System. We would like to thank Joseph Cox, Michael Gibson, Beverly Hirtle, Andreas Lehnert, and Molly Mahar for their helpful comments. We also thank Sarah Harper for her editorial review of the draft. Return to text

2. For details on supervisory expectations in CCAR, see Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Capital Planning at Large Bank Holding Companies: Supervisory Expectations and Range of Current Practices (August 2013); and Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review 2014: Summary Instructions and Guidance (November 2013). Return to text

3. See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, The Supervisory Capital Assessment Program: Design and Implementation (May 2009) Return to text

4. The tier 1 common capital ratio is defined as tier 1 capital less the non-common elements of tier 1 capital, including perpetual preferred stock and related surplus, minority interest in subsidiaries, trust preferred securities and mandatory convertible preferred securities, divided by risk-weighted assets. Return to text

5. See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, press release, November 9, 2009. Return to text

6. See B. Hirtle, T. Schuermann, and K. Stiroh, "Macroprudential Supervision of Financial Institutions: Lessons from the SCAP," Federal Reserve Bank of New York,Staff Report No. 409 (2009); and S. Peristiani, D. Morgan, and V. Savino, "The Information Value of Stress Test and Bank Opacity," Federal Reserve of Bank of New York, Staff Report no. 460 (2010). Return to text

7. One of the 19 BHCs that participated in the SCAP, MetLife Inc, deregistered as a BHC in 2012 by selling its bank subsidiary and is no longer part of CCAR. Return to text

8. See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, "Capital Plans," final rule, 76 Fed. Reg., no. 231, 74631–74648 (2011). Return to text

9. BHCs with $50 billion or more in total consolidated assets must conduct another set of stress tests (mid-year stress tests) each year, using three sets of scenarios they develop and publish the results. See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, "Supervisory and Company-Run Stress Test Requirements for Covered Companies," final rule, 77 Fed. Reg., no. 198, 62378–62396 (2012). Return to text

10. The capital plan and stress testing rules define a capital action as "any issuance of a debt or equity capital instrument, capital distribution, and any similar action that the Federal Reserve determines could impact a large bank holding company's consolidated capital." A capital distribution includes dividend payments or share repurchases. Return to text

11. However, common stock issuance associated with expensed employee compensation is incorporated in the analysis. Return to text

12. See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Dodd-Frank Act Stress Test 2013: Supervisory Stress Test Methodology and Results (March 2013). Return to text

13. See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review 2013: Assessment Framework and Results (March 2013). Return to text

14. Key elements of this assessment are discussed in detail in Capital Planning at Large Bank Holding Companies: Supervisory Expectations and Range of Current Practice (August 2013), (available at www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/bcreg/20130819a.htm). Return to text

15. See B. Bernanke, "Stress Testing Banks: What Have We Learned?" Speech at Maintaining Financial Stability: Holding a Tiger by the Tail, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Stone Mountain, Georgia (2013); and T. Schuermann, "The Fed's Stress Tests Add Risk to the Financial System," The Wall Street Journal, March 19, 2013. Return to text

16. See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review 2012: Methodology and Results for Stress Scenario Projections (2012); and Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Dodd-Frank Act Stress Test 2013: Supervisory Stress Test Methodology and Results (2013). Return to text

17. See I. Goldstein and H. Sapra, "Should Banks' Stress Test Results Be Disclosed? An Analysis of the Costs and Benefits," Working Paper,(2013); and T. Schuermann, "Stress Testing Banks," Wharton Financial Institutions Center (2013). Return to text

18. Starting with CCAR 2014, both supervisory and company-run stress test projections must reflect revised capital rules that will become effective for the largest BHCs on January 1, 2014, with required phasing-in of various components. Return to text

19. See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, "Proposed Rule on Enhanced Prudential Standards and Early Remediation Requirements for Foreign Banking Organizations and Foreign Nonbank Financial Companies" (2012). Return to text