FEDS Notes

October 31, 2014

Introducing Actuarial Liabilities and Funding Status of Defined-Benefit Pensions in the U.S. Financial Accounts

Irina Stefanescu and Ivan Vidangos

Last year, in its September 2013 release, the Financial Accounts of the United States (formerly known as Flow of Funds accounts) changed the treatment of defined-benefit (DB) pensions from a cash accounting basis to an accrual accounting basis. Under accrual accounting, pension plans' liabilities are set equal to the present value of future DB benefits that plan participants have accumulated to date, which are calculated using standard actuarial methods. As a result of this change, the Financial Accounts now provide a measure of the funding status of private and public DB pension plans. The accounting change also had other important effects on the balance sheets--and corresponding financial flows--of the private and public pensions sectors, the nonfinancial business sector, the government sector, and the household sector. This note discusses the accounting changes and their main effects in the Financial Accounts, including the new measures of funding status of private and public DB pension plans.

1. Overview

Defined-benefit (DB) pension plans are employer-sponsored retirement plans in which workers are promised a fixed pension after retirement in the form of an annuity. The benefit is typically linked to the participant's final wage and the number of years of service, with the exact formula varying by employer. DB pension plans are offered by some private employers, as well as by the federal and state and local (S&L) governments.1

The Financial Accounts report assets and liabilities (and corresponding financial flows) for both private and public (federal as well as S&L) DB pension funds.2 Prior to September 2013, the assets and liabilities of DB pension plans were reported using cash accounting principles, which record the revenues of pension funds when cash is received and expenses when cash is paid out. Under this treatment, there was no measure of a plan's accrued actuarial liabilities--i.e., the present value of earned future benefits--rather, the liabilities in the Financial Accounts were set equal to the plans' assets. As a result, the Financial Accounts did not report any measure of underfunding or overfunding of the pension sector's actuarial liabilities, as would occur if the assets held by the pension sector fell short of or exceeded the liabilities.

Starting with the September 2013 release, the Financial Accounts treat DB pensions using accrual accounting principles, whereby the liabilities of DB pension plans are set equal to the present value of future DB benefits that participants have accumulated to date, which are calculated using standard actuarial methods.3 These actuarial liabilities of the DB pension sector are treated as an asset of the household sector.

Additionally, the difference between actuarial liabilities and pension fund assets is now reported in the Financial Accounts as a new item, called "claims of pension fund on sponsor", which reflects the amount of underfunding or overfunding of the plans. These claims (which can be positive or negative) are treated as an asset of the pension funds sector and a liability of the sponsors of the plans (e.g. the employers in the nonfinancial corporate business, the federal government, or S&L government sectors).

The transition to an accrual accounting method is an acknowledgement that DB pension accruals typically represent legally binding contractual agreements between employers and their employees, and that they should therefore be treated as liabilities of the DB plans' sponsors and as assets of households, regardless of the current funding status of the pension plan. This is consistent with the international standards recommended in the revised System of National Accounts (SNA 2008).4 Reflecting SNA terminology, we refer to accrued liabilities as "pension entitlements" in the Financial Accounts.

In addition to these accounting changes, the Financial Accounts added two new tables in its September 2013 release, titled "Private and Public Pension Funds" (tables F.116 (PDF) and L.116 (PDF)), which aggregate the three pension sectors (private, federal, and S&L). These tables also include as memo items a breakdown of total household retirement assets held in tax-deferred accounts, including: DB and defined-contribution (DC) pension plans, individual retirement accounts (IRAs), and annuities at life insurance companies. Finally, a memo item was added to each of the pension-fund levels tables (tables L.116 (PDF) through L.119 (PDF)), showing the aggregate funding status--i.e., plan assets relative to accrued actuarial liabilities--of the DB plans in each of the three sectors.

2. Measurement of actuarial pension liabilities (entitlements)

End-of-quarter actuarial liabilities of private and public pensions in the Financial Accounts are estimated based on annual estimates of pension entitlements produced by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).5 For private and S&L government pension plans, the BEA calculates pension fund liabilities using an accumulated benefit obligation (ABO) method, which measures the present value of earned future benefits calculated based on current salaries, tenure, and life expectancy assumptions. For federal government pension plans, the BEA calculates liabilities using a projected benefit obligation (PBO) method, which incorporates projected future salary growth, in order to maintain consistency with the main published actuarial estimates of federal pension plans. The choice of discount rate in the present-value calculation is consequential and subject to some debate (see e.g., Novy-Marx and Rauh, 2011). For private and S&L plans, the discount rates used by the BEA, and hence in the Financial Accounts, are based on AAA-rated corporate bond rates; for federal government plans, they are based on the rates assumed by the actuaries in preparing their annual reports.6

3. Impact on the Financial Accounts

The effects of the pension accounting change on the Financial Accounts depend on the funding status of the plans, which varies over time. The fundamental change is to count as household wealth the present value of accrued benefit obligations, rather than the current level of pension fund assets. When pension funds are underfunded (as has been the case in recent years for private, federal, and S&L pension funds), the new accounting treatment, relative to the previous treatment, results in:

- Higher pension wealth and therefore higher net worth of the household sector, reflecting the inclusion of unfunded accrued promises. Previously the unfunded promises were ignored; now they are treated as assets of households and liabilities of pension plans.

- New claims of pension funds, in turn, on the sponsors of DB pension plans, reflecting the sponsors' obligation to fully fund its accrued promises. These are assets of the pension funds and liabilities of the sponsors.

Thus, in effect, the new treatment creates a new asset for households, equal to unfunded accrued pension promises, which is ultimately borne as a liability by the plan sponsors in the corporate, S&L, and federal government sectors. The pension fund sectors act as intermediaries between sponsors and households, and thus the unfunded promises appear on both sides of their balance sheets. Note that when DB pension plans are overfunded (an infrequent occurrence), the new treatment of DB pensions results in lower household pension wealth and smaller liabilities for the plan sponsors than the previous treatment.7

3.1. Effect on private pension funds

Table L.117.b (PDF) (Private Pension Funds: Defined Benefit Plans), reproduced here from the Second Quarter 2014 release of the Financial Accounts (see the Supplements section), shows the assets and liabilities of private DB pension funds.8

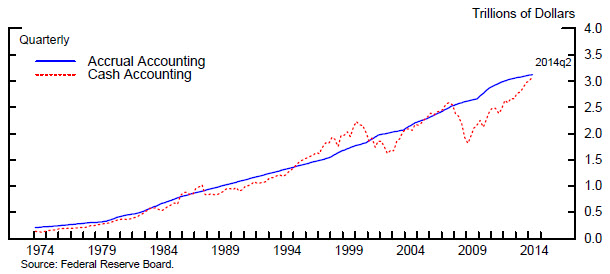

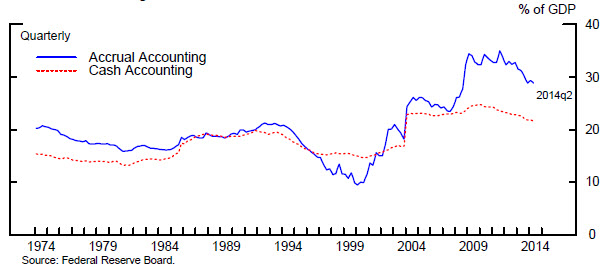

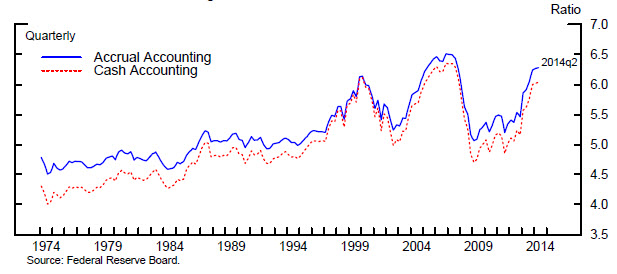

Under the accrual treatment of DB pensions, line 19, labeled "Pension entitlements (liabilities)", shows the actuarial liabilities accrued by the plans' beneficiaries, estimated at $3.1 trillion for 2014q2. Figure 1 shows the sector's DB liabilities under both the new (accrual) and old (cash) treatment of DB pensions, on a quarterly basis, from 1974q1 to 2014q2. As can be seen, private DB pension liabilities under accrual and cash accounting were relatively close to each other until the late 1990s, when the stock-market boom led many plans to be overfunded. Under the previous accounting, which equated liabilities to assets, the run-up in assets resulted in a run-up in liabilities as well. Similarly, the sharp drop in assets in 2008 led to a sharp drop in liabilities as well, under the previous accounting treatment. By contrast, liabilities under accrual accounting continued to climb in a relatively smooth fashion, with a bit of an acceleration in 2010 due to the reduction in interest rates. The gap between the two series has been slowly narrowing since early 2009 and is now nearly closed.

Since the dashed red line is equal to plan assets, the difference between the blue line and the dashed red line is equal to the claims on the sponsor of the plans (in this case, the nonfinancial corporate business sector), and represents the level of underfunding (when the blue line is above the dashed red line) or overfunding (when the dashed red line is above the blue line). These claims are also reported in line 17 of Table L.117.b, and were estimated to be $31.7 billion in 2014q2.

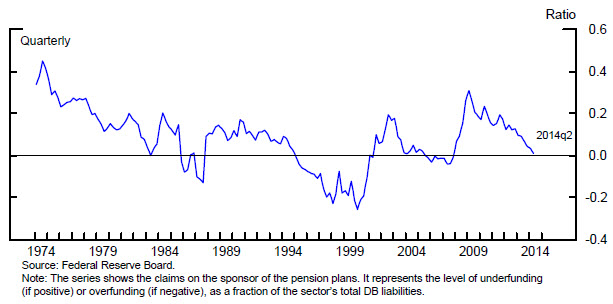

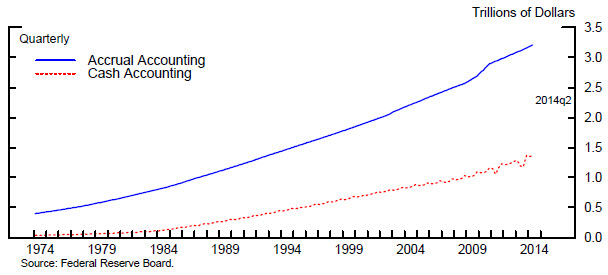

Figure 2 shows the claims on the sponsor as a ratio of total DB liabilities of the sector. As can be seen, private DB pension funds were overfunded (indicated by negative values of the ratio) in the late 1990s, in large part as a result of the strong stock market performance of the 1990s. The plans' funding situation deteriorated markedly with the burst of the dot-com bubble in 2000-2001, stabilized in the mid-2000s, and then deteriorated further with the financial crisis of 2008-2009, when the "unfunded ratio" climbed to about 30 percent of total private pension liabilities. The unfunded ratio has been declining gradually towards zero since then. That is, the financial situation of private pension funds has improved substantially since the time of the financial crisis, and the funds are almost back to being fully funded.9

3.2. Effect on the nonfinancial corporate business sector

The effect of the accounting change on the balance sheet of the nonfinancial corporate business sector can be seen in Table L.102 (PDF), which shows the assets and liabilities of nonfinancial corporate businesses. Under the accrual accounting of DB pensions, total liabilities (line 22) include the claims of private pension funds on nonfinancial corporate businesses (the sponsors of the plans); these claims ($31.7 billion in 2014q2) are reported on line 35 and come from line 17 of Table L.117.b. With total liabilities of the sector running at $16.2 trillion in 2014q2, the change in the treatment of DB pensions has a fairly modest effect on the bottom line of nonfinancial corporate businesses in recent quarters, reflecting the relatively small amount of current underfunding.

3.3. Effect on S&L pension funds

The effects of the accounting change on the S&L pensions sector can be seen in Table L.118.b (PDF), which shows the assets and liabilities of DB pension funds sponsored by S&L governments. This sector includes the DB retirement plans of state governments and local government entities such as counties, municipalities, townships, school districts, and special districts.10

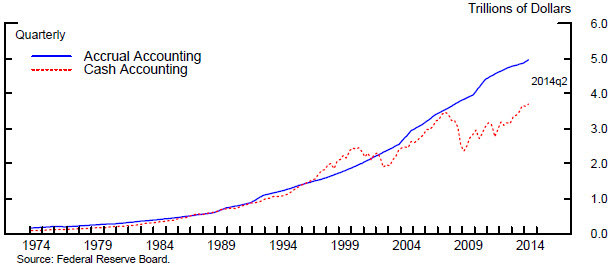

Line 18 of L.118.b, labeled "Pension entitlements (liabilities)", shows the actuarial liabilities accrued by the beneficiaries of the DB plans, which is estimated at about $5.0 trillion in 2014q2. Figure 3 shows the sector's DB liabilities under both accrual and cash accounting of DB pensions, and as was the case with the private plans shown above, the difference between the blue line and the dashed red line represents the amount of underfunding. Unlike private plans, however, substantial underfunding remains in the state and local government pension sector. The difference, i.e. the claims on the sponsor of the plans (S&L governments), is reported in line 16 of Table L.118.b, and was estimated to be about $1.3 trillion in 2014q2.

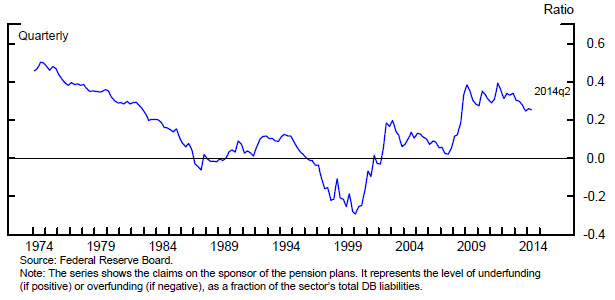

Figure 4 shows these claims on the sponsor as a ratio of total DB liabilities of the sector. In the most recent quarters, unfunded liabilities of S&L pension funds have been running at around 25 percent of total DB liabilities of the sector.

3.4. Effect on S&L governments

The effect of the new pension accounting treatment on the balance sheet of S&L governments can be seen in Table L.104 (PDF), which shows the financial assets and liabilities of the S&L government sector. Under the accrual treatment of DB pensions, total liabilities (line 18) include the claims of S&L government pension funds on S&L governments; these claims are reported on line 25 of the table (and come from line 16 of Table L.118.b).

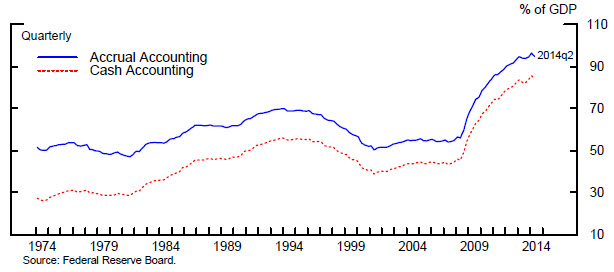

Figure 5 shows the total liabilities of S&L governments with and without the inclusion of "claims of pension fund on sponsor" (i.e. under accrual and cash accounting of DB pensions), expressed as a percent of GDP. As can be seen, the inclusion of these claims increases the total liabilities of S&L governments from about 22 percent of GDP to about 29 percent of GDP in the most recent quarters. That is, the shift in the treatment of DB pensions to an accrual accounting basis substantially raises the estimated financial obligations currently faced by S&L governments.

3.5 Effect on federal pension funds

Table L.119.b (PDF) shows the assets and liabilities of federal government DB plans.11 Line 10, labeled "Pension entitlements (liabilities)", shows the total liabilities of DB pension plans sponsored by the federal government, representing the benefits that have accrued to the beneficiaries to date, estimated to be $3.2 trillion in 2014q2.

Figure 6 shows the liabilities of federal DB pension plans under accrual and cash accounting of DB pensions. This pattern is notably different from that of private and S&L pension plans--in particular, liabilities under accrual accounting are significantly higher than under cash accounting in all years. The difference between the two series, or "claims of pension fund on sponsor", is shown in line 9 of Table L.119.b, and was estimated to be about $1.8 trillion in 2014q2.

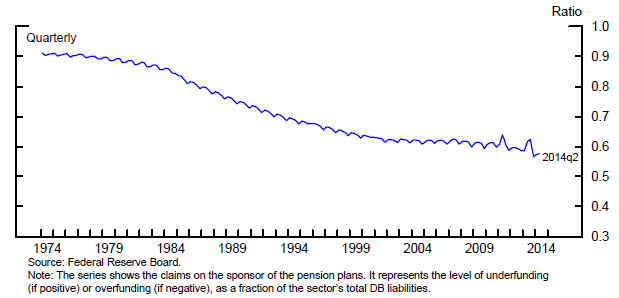

This pattern is shown in another way in Figure 7, which displays the claims on the sponsor as a ratio of total DB liabilities of the sector (i.e. the "unfunded ratio"). Historically, DB pensions sponsored by the federal government were funded on a pay-as-you-go basis--that is, there were few (if any) assets set aside to pay future benefits.. This was the case, for example, for the Civil Service Retirement System (CSRS), which was established in 1920 and was the main federal DB pension plan until the establishment of the Federal Employees' Retirement System (FERS) in 1986.12 As a result, federal government DB pension plans were largely unfunded for several decades, as illustrated in Figure 7 by an unfunded ratio of close to 90 percent of total liabilities of the sector in the 1970s. In the 1980s, the FERS--which was designed to be essentially fully funded--was introduced to gradually replace the CSRS, leading to a decrease in the unfunded component of federal DB pension liabilities.13 Additionally, in recent decades, the Treasury Department has been required to make "catch-up" payments to the federal DB pension funds from its general fund in order to gradually close the funding gap in federal DB pensions. As a result, the unfunded component has decreased from about 90 percent to about 58 percent of total DB liabilities of the sector.

One important difference between federal and S&L (or private) DB pensions, however, is that federal DB pension funds are invested almost exclusively in special-issue, nonmarketable Treasury securities.14 As a result, unlike private and S&L pension funds, the "asset holdings" of federal DB pension funds are not assets that can be sold in private markets in order to fund future benefits. Instead, they represent claims on the Treasury, and therefore the balances of the federal pension funds are available for future benefit payments only in a bookkeeping sense.15 ,16

3.6 Effect on the federal government

The effect of the pension accounting change on the balance sheet of the federal government can be seen in Table L.105 (PDF), which shows the assets and liabilities of the federal government. Total liabilities (line 15), estimated at $16.4 trillion in 2014q2, include the claims of pension plans on the federal government (the sponsor of the plans); these claims are shown in line 29 of the table (and come from line 9 of Table L.119.b).17

Figure 8 shows the total liabilities of the federal government with and without the inclusion of "claims of pension fund on sponsor" (i.e. under accrual and cash accounting of DB pensions), as a percent of GDP. As can be seen, the inclusion of these claims raises the total liabilities of the federal government by about 10 percentage points of GDP in the most recent quarters (e.g. from 85 percent to 95 percent of GDP in 2014q2).18 That is, as in the case of S&L governments, the shift to accrual accounting of DB pensions significantly raises this measure of the financial obligations of the federal government.

| Figure 8: Total Liabilities of the Federal Government Under Accrual and Cash Accounting of DB Pensions |

|---|

|

3.7. Effects on household wealth

As already discussed, under the new pension accounting treatment, pension entitlements (i.e., accrued benefits promised to be paid in the future) are considered an asset of the household sector, regardless of current funding status.19 Because pension funds have been underfunded more often than overfunded, the new treatment has generally increased the value of household pension wealth and therefore the net worth of the household sector. That is, household wealth now includes the full value of accrued pension promises, not just the currently funded component. This effect can be clearly seen in Table L.100 (PDF), which shows the financial assets and liabilities of households and nonprofit organizations. The main effect of the transition to accrual accounting of DB pensions can be seen in line 21 of the table, which shows a new asset on household balance sheets--claims of pension funds on sponsors, representing the total value of unfunded DB pension promises from private plans, S&L plans, and federal plans. As the table shows, including the unfunded pension liabilities increases the assets, and therefore the net worth, of the household sector by $3.1 trillion in 2014q2.20

Figure 9 shows household net worth under accrual and cash accounting of DB pensions, expressed as a ratio to disposable personal income. As the figure shows, the accrual treatment of DB pensions raises the ratio in most years of the last four decades (except in the late 1990s, when both private and S&L pension funds were overfunded, but federal pensions were underfunded). Over the previous five years, the accounting change increases the net worth ratio by an average of about 0.3, or 30 percent of aggregate annual income.

| Figure 9: Household Net Worth Relative to Disposable Personal Income under Accrual and Cash Accounting of DB Pensions |

|---|

|

References

Novy-Marx, Robert, and Rauh, Joshua, "Public Pension Promises: How Big Are They and What Are They Worth?", Journal of Finance 66(4), 2011, 1207-1245.

Reinsdorf, Marshall, David Lenze, and Dylan Rassier (2014), "Bringing Actuarial Measures of Defined Benefit Pensions into the U.S. National Accounts". Paper prepared for the IARIW 33rd General Conference, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, August 2014. Available at http://www.iariw.org/papers/2014/ReinsdorfPaper.pdf ![]() .

.

US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (2013), "National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2013," Bulletin 2776 (September). Available at http://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2013/ebbl0052.pdf.

1. In the private sector, the use of DB plans has been declining since the early 1980s. In March 2013, about 16% of private sector workers participated in a DB plan (US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2013). In contrast, in the public sector, most workers participate in DB pension plans. Return to text

2. The Financial Accounts do not include Social Security, which is a social insurance program rather than an employer-sponsored retirement program. Return to text

3. These changes in the treatment of DB pensions in the Financial Accounts were introduced in coordination with the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), which also changed its treatment of DB pensions in the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) from a cash to an accrual accounting basis starting in July 2013, as part of its 2013 comprehensive revision. Return to text

4. The revised System of National Accounts (SNA 2008) was jointly produced by the United Nations, the European Commission, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank Group, and is available at http://unstats.un.org/unsd/nationalaccount/docs/SNA2008.pdf ![]() . Return to text

. Return to text

5. The BEA started reporting these estimates in their July 2013 release of the National Income and Product Accounts, when it adopted the accrual accounting of DB pensions. Return to text

6. For details, see Reinsdorf, Lenze, and Rassier (2014). In particular, see Table B1 of their paper for the discount rates used by BEA in the calculation of liabilities for private and S&L pension plans, and table B2 for the discount rates used for federal plans. Return to text

7. That is, our previous treatment overestimated household pension wealth when DB plans were in overfunded positions. Return to text

8. The difference between total financial assets and liabilities in the table reflects nonfinancial assets, which consist primarily of real estate investment assets. All underfunding of private pensions is attributed to the nonfinancial corporate business sector, because financial firms represent only a very small share of underfunding. The balance sheet of private DC plans is shown in table L.117.c, and the combined balance sheet of private DB and DC plans is shown in L.117. Return to text

9. This improvement also reflects in part the effect of private pension funds selling liabilities to insurance companies in recent years, which effectively eliminates the pension liabilities from the sponsors' books. Return to text

10. Starting with the September 2014 release of the Financial Accounts, we report data for the defined-contribution plans sponsored by S&L governments (mostly 403(b) and 457 plans), as well as for DB plans. A forthcoming FEDS Note will provide additional details about the data used for S&L DC plans. As in the case of private pension funds, the small difference between total financial assets and liabilities in the pension tables reflects nonfinancial assets, which consist primarily of real estate investment assets. Return to text

11. The DB plans include the Civil Service Retirement and Disability Fund (CSRDF), Military Retirement Fund, Railroad Retirement Board, Judicial Retirement Fund, and Foreign Service Retirement and Disability Fund. The federal government also sponsors a DC plan, consisting largely of the Thrift Savings Plan (TSP). Return to text

12. Under both the CSRS and FERS, DB pension benefits are paid out of the Civil Service Retirement and Disability Fund (CSRDF). Return to text

13. Military retirement was also essentially funded on a pay-as-you-go basis until 1984, when the Military Trust Fund was established. Return to text

14. These nonmarketable Treasury securities represent intragovernmental debt, or debt that the government owes to itself. They are part of federal debt subject to the statutory debt limit (though they are not part of federal debt held by the public). Note that, by contrast, the unfunded portion of federal DB pension liabilities is not part of federal debt subject to the statutory limit. Return to text

15. This may be viewed as a decision by the federal government to pay future pension benefits out of future revenues (or future borrowing). Return to text

16. The two blips seen in the series around 2011q2 and 2013q2-q3 reflect the use of "extraordinary measures" by the Treasury Department at the time of the federal debt-limit standoffs of 2011 and 2013. See Feds Note "The Federal Debt-Limit Standoff of 2013 in the Financial Accounts of the United States", available at http://www.federalreserve.gov/econresdata/notes/feds-notes/2014/federal-debt-limit-standoff-of-2013-in-the-financial-accounts-of-the-united-states-20140421.html. Return to text

17. In addition to the underfunding or overfunding of federal DB pension plans, these claims also include suspended investments in the Thrift Savings Plan (TSP) G Fund. Suspending investments in the G Fund is one of the "extraordinary measures" available to the Treasury Department when operating at the federal statutory debt limit. Suspended investments in the G Fund are typically zero, but have been large around periods characterized by legislative standoffs over raising the debt limit. See Feds Note "The Federal Debt-Limit Standoff of 2013 in the Financial Accounts of the United States", available at http://www.federalreserve.gov/econresdata/notes/feds-notes/2014/federal-debt-limit-standoff-of-2013-in-the-financial-accounts-of-the-united-states-20140421.html. Return to text

18. Both series in the figure include nonmarketable Treasury securities held by federal pension funds (but not by Social Security). There is a debate in the international arena about whether the "correct" measure of debt should or should not include claims from public pension plans on the government. Return to text

19. Under cash accounting, only the current financial assets of DB plans were treated as an asset of the household sector. Return to text

20. Table B.100 in the Balance Sheets section of the Financial Accounts shows the balance sheet of households and nonprofit organizations including both financial and nonfinancial assets. Line 28 of that table shows total pension entitlements of the household sector (private and public, DB and DC), including claims on the sponsor of the plans. Return to text

Please cite as:

Stefanescu, Irina, and Ivan Vidangos (2014). "Introducing Actuarial Liabilities and Funding Status of Defined-Benefit Pensions in the U.S. Financial Accounts," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, October 31, 2014. https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.0034

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board economists offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers.