Assembly and Uses of a Data-Sharing Network in Minneapolis

- Market Conditions in Minneapolis: High Levels of Foreclosures and Vacancies

- Formation of the Vacant House Project Coalition: Addressing Safety and Liveability

- Developing Data Sets to Inform Remediation Strategies

- Using Data to Inform Policy Options

- Next Steps in the Vacant House Project

- Strategies Other Communities Can Use to Establish Data-Sharing Models

Like many cities across the country caught up in the previous decade's housing boom and bust, Minneapolis is experiencing mortgage-default problems on a scale not seen since the Great Depression. Foreclosed properties and vacant homes are dotted across the city, with concentrations in some particularly hard-hit lower-income areas. In dealing with the slew of direct and indirect consequences, Minneapolis has benefited from a history of openness and information sharing among local nonprofits, neighborhood organizations, city and county agencies, and academic institutions. This broad coalition of partners has developed a strong, data-driven network to help identify vacant properties for remediation and guide neighborhood stabilization efforts. Fortunately, other cities can replicate this model and build a coalition of data providers to meet any number of needs.

This article provides a snapshot of the housing situation in Minneapolis in recent years and highlights how the city created and used a data-sharing network to develop stabilization strategies that focus on individual properties within neighborhoods.

Market Conditions in Minneapolis: High Levels of Foreclosures and Vacancies

Since 2005, Minneapolis has experienced a wave of foreclosures that has touched every neighborhood in the city. The citywide foreclosure rate crested in 2008 at 3.1 percent of residential parcels, and while this number pales in comparison to cities like Las Vegas and Phoenix, the percentage of foreclosures reached nearly 11 percent in some Minneapolis neighborhoods. The North Minneapolis neighborhood, where approximately 17 percent of the city's residential parcels are located, had the dubious distinction of containing nearly 4 in 10 of Minneapolis's foreclosures in 2010.

Vacancies provide an even starker indicator of an area's economic and social health, with North Minneapolis leading the city in vacancies. The city's official Vacant Building Registration (VBR) program,1 which tracks vacant buildings and assesses fees to property owners, recognizes nearly 500 North Minneapolis family residences as being vacant. But other data--discussed later in this article--suggest a number closer to 1,600. The recently elevated level of vacant properties in North Minneapolis--on the heels of a housing market surge stoked by speculation, mortgage fraud, subprime lending, and rental property investment--has contributed to an increase in property crimes.

Formation of the Vacant House Project Coalition: Addressing Safety and Liveability

The 4th Precinct Community and Resource Exchange (CARE) Task Force responded. Active since 1998, the CARE Task Force is an assembly of city, county, and community representatives, including many long-time North Minneapolis neighborhood residents, that promotes safety and livability in Minneapolis's 4th police precinct through crime prevention and alerts. The CARE Task Force convened a group of stakeholders to initiate the Vacant House Project (VHP). The task force began by strategizing with a representative of the Minneapolis Police Department on solutions to the growth in property crime, including copper theft. According to the police department, thieves were entering primarily vacant homes and stripping them of copper, causing substantial damage that ranged from flooded basements to torn-up floor boards to smashed walls. Conversations with real estate investors, developers, and general contractors indicated that, in many cases, the damage to these residences was so severe that the cost of buying and repairing these homes was too steep to justify financially. In addition, the demand for owner-occupied housing on the north side is weak. As a result, the task force advocated a comprehensive approach that would include a portfolio of options, such as land banking, strategic demolition, and well-managed rentals. The first priority, however, was to identify which houses were vacant. For this, they needed to enlist additional partners to aid in the VHP.

In January 2011, the group reached out to the University of Minnesota's Center for Urban and Regional Affairs (CURA) to help lead the effort to identify vacant houses for protection from vandals and thieves and for assessment of appropriate disposition options (e.g., rehabilitation, demolition, land bank, rental, etc.). For more than 40 years, CURA has operated as an applied research and technical assistance center that connects the resources of the University of Minnesota with the interests and needs of urban communities and the broader Twin Cities region. CURA maintains working relationships with scores of municipal offices and nonprofits, which has enabled it to gather and synthesize data streams from disparate sources for hundreds of projects. CURA was thus well positioned as a trusted broker of information to lead a data collection effort to create a database of indicators of housing vacancy and distress.

Other partners affected by the housing conditions in North Minneapolis were invited to join this effort, with the goal of establishing fact-based, data-driven strategies to address the ailing housing market in North Minneapolis. The roster of participating parties grew to include the following:

- various offices and departments within the City of Minneapolis, which provided water-meter data, properties slated for demolition, the official list of vacant buildings, and guidance on remediation strategies

- Hennepin County, which provided parcel data, foreclosure listings, REO properties, tax delinquency and forfeitures, and sheriff sale dates

- the Minneapolis Police Department, 4th Precinct, which provided a listing of properties that encountered copper theft

- the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Community Development Department, which provided technical assistance and statistics on mortgage originations and mortgage foreclosure and delinquency rates

- Pohlad Family Foundation, which provided funding and project guidance

- Folwell Neighborhood Association and Webber Camden Neighborhood Association, whose members provided on-the-ground visual reports of homes that appeared to be vacant (referred to as "windshield surveys") and local Multiple Listing Service data

- Twin Cities Community Land Trust, which provided information on properties available through the NSP First Look Program 2

- CURA, which acted as technical lead and central partner in data collection and analysis

Together, the partners created a list of data elements that could be used to help identify vacant and distressed properties (see box 1).

Box 1. Data Elements Used to Identify Vacant and Distressed Properties

After consulting with partners of the Vacant House Project (VHP) about useful and--importantly--available data, the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs (CURA) assembled the following data sets to help identify vacant and distressed properties:

Vacancy Indicator

- Zero or low water usage

- Copper theft

- REO properties

- Official Vacant Building Registration

- Windshield survey of vacant properties

- Properties slated for demolition

- U.S. Postal Service tract-level vacancy data

Legal Judgment

- Foreclosure filings

- Tax delinquency

- Sheriff sales

- Mortgage delinquency rates

Other Tools

- Parcel data 3

- Multiple Listing Service data

- NSP-First Look data

1. Includes sale date, estimated market value, owner name, lot size, and property tax assessments, among other categories pertinent to the legal status of land and the structure on it. Return to text

Developing Data Sets to Inform Remediation Strategies

Based on its knowledge of neighborhood-level data4 and extensive experience assisting neighborhood organizations and local governments with the use of these data to identify issues and problems, CURA gathered a roster of data sets that was not only useful in identifying vacant and distressed properties but also helpful in developing strategies for remediation. In fact, CURA already possessed several data elements needed to create this database, including parcel data, foreclosures, sheriff sales, and the city's official VBR list. Obtaining most of the remaining information required little more than contacting those officials who had access to the pertinent data, many of whom had worked with CURA and members of the coalition in the past. There were few administrative or legal barriers preventing the acquisition of data in a timely matter, and CURA was able to assemble the bulk of the indicator data in spreadsheets and mapping files in just a few weeks, with no cost other than staff time. At that point, CURA was able to provide statistics, tables, and maps to the city, county, and community decisionmakers in the VHP.5

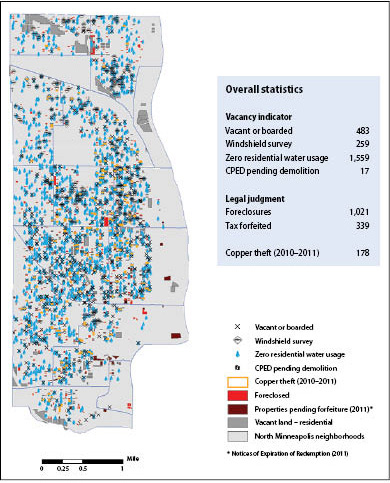

Ultimately, when all of these data elements were mapped using Geographic Information System software (GIS)--an essential tool in determining the accuracy of the data and extent of the vacancy problem--a composite picture of Minneapolis's north side emerged that revealed clear areas of concern (see figure 1).

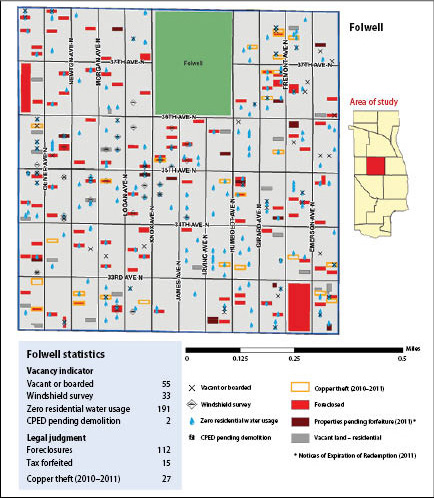

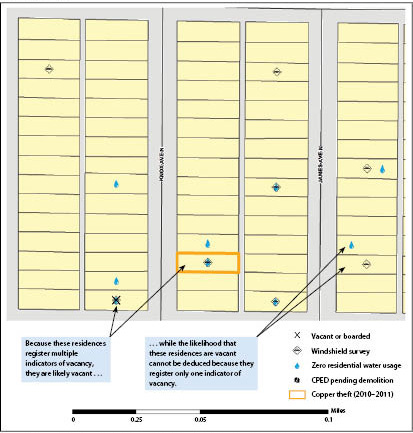

The splash of data points that dot the parcel map in figure 1 represents a snapshot of the housing situation in North Minneapolis in mid-2011. Visibly, this much is clear: some areas appear more stable while others appear distressed. At a finer scale, however, the picture is sometimes still fuzzy. While a single indicator does not necessarily mean that a house is vacant, the likelihood of vacancy increases as multiple indicators begin to stack up on a single parcel (see figure 2 and figure 3). In short, though the status of individual properties can remain uncertain, the coalition now has a much-improved picture of the scope of its vacant property problem and the areas most severely affected.

Source: Hennepin County; City of Minneapolis; Folwell Neighborhood Association; CURA. Data compiled by CURA as part of the 4th Police Precinct Vacant Properties Project.

Source: Hennepin County; City of Minneapolis; Folwell Neighborhood Association; CURA. Data compiled by CURA as part of the 4th Police Precinct Vacant Properties Project.

Source: Hennepin County; City of Minneapolis; Folwell Neighborhood Association; CURA.

Using Data to Inform Policy Options

By the spring of 2011, the coalition had begun to put its new database to use as a neighborhood stabilization tool, using the data to sketch out a range of options to address crime prevention and reinhabitation, summarized in table 1:

| Preventing property damage | Reinhabiting and selling vacant homes | |

|---|---|---|

| Ongoing | Temporary | Long-term |

| Require water shut-off as soon as home is vacant | Rent homes to individuals on Section 8 (if subsidies are available) | Target down-payment assistance to homes on "quick sales possible" list |

| Train and pay neighbors, via neighborhood organizations, a small stipend to maintain and watch homes (e.g., cut grass, pick up trash, etc.) | House families on nonprofit waiting lists (e.g., Urban Homeworks) | Determine which homes can be sold quickly; use network of North Minneapolis realtors and targeted subsidies to put homes back in service |

| Create local, private report system for use by neighbors to report changes in vacant homes | Allow use of homes as transitional housing for families leaving shelters | Create incentive fund for North Minneapolis realtors working together to share potential buyers who are willing/able to purchase homes |

| Train local U.S. Postal workers to "check in" with reporting system above | Create list of college students willing to rent vacant homes | Reduce city regulatory barriers to home improvement (e.g., lead abatement, number of residents per home) |

The new data also raised significant questions about the accuracy of the data that policymakers rely on. Since the VBR list accounts for only about a quarter of the properties believed to be vacant (as mentioned earlier), the city could be losing millions of dollars in vacant property fees as well as failing to adequately address vacant property issues.6 In addition, the vacancy maps reveal that the number of parcels with little or no reported water usage far exceeds other indicators of vacancy, raising the previously unrecognized prospect that many thousands of the city's residential water meters may be broken or malfunctioning.

Next Steps in the Vacant House Project

The coalition is continuing to work with CURA to enhance the database, even as it is beginning to apply it to neighborhood stabilization issues. One potential avenue for enhancing the database is using the methodology of the Foreclosure Risk and Housing Market Indexes developed by the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) in conjunction with the local data at CURA's disposal. Recognizing that most municipalities have finite financial and human resources, LISC created indexes based on foreclosure risk and housing market strength to help policymakers identify the areas in their jurisdictions that would respond best to specific remediation and stabilization efforts. While the indexes provided by LISC produce census-tract-level maps, CURA could use data from the VHP database to produce census-block-level maps of Minneapolis's north side that could help policymakers prioritize their resources on certain areas and specific properties.

The accuracy of the maps developed using this approach would depend greatly on the type and quality of the data that CURA collects. While many of the indicators that CURA has so far collected to identify vacant or distressed houses are similar or identical to those used by NEO CANDO (whose efforts are discussed in more detail in the first article of this compilation), the VHP also utilizes information on the location of copper pipe theft, the city's official VBR list, and the city's list of houses slated for demolition. Using additional indicators not just to detect vacancy but also to determine the foreclosure risk and housing market strength of each block could add even more richness to the database, though fees for the data and privacy issues still need to be considered. For instance, every four years assessors for the city rate the condition of every structure in Minneapolis, and the city is willing to provide this information to the VHP for free. Adding this information could help refine the remediation and stabilization measures taken for each structure. For example, if a vacant house that is assessed as being in poor physical condition is located on a block with a weak housing market and high foreclosure risk, the city may be more inclined to demolish the property rather than attempt to rehabilitate it. On the other hand, CURA is exploring the possibility of adding more utility information--such as zero electricity and gas usage, as well as garbage removal--to help determine the likelihood of vacancy, but the costs and the availability of these datasets are still unknown, as is the usefulness of the information.

Strategies Other Communities Can Use to Establish Data-Sharing Models

Jump to:

The data from the VHP--and, more importantly, the network supplying the data--are likely to play central roles in many additional neighborhood stabilization initiatives going forward (box 2 offers an unusual but critical example of this ).7 In fact, the coalition that formed around the VHP represents just a cross-section of sources that CURA regularly calls on for information. As an active participant in civic and neighborhood affairs for more than four decades, CURA has developed productive relationships with municipal departments and other nonprofits across the Twin Cities. And although not all areas of the country have a prominent organization like CURA to act as data and information facilitators, it takes only a proactive neighborhood organization, nonprofit, or even municipal agency to begin the process of establishing one.

Box 2. Sharing Data to Aid a Tornado Recovery Effort

A tornado with winds topping 110 miles per hour ripped through North Minneapolis May 22, 2011, leaving a scar nearly four miles long and damaging nearly 1,900 properties. The damage assessments, which were conducted by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), found that 274 properties sustained major damage (i.e., homes had structural or significant damages, were uninhabitable, and required extensive repairs) and that 1,608 properties sustained minor damage (i.e., homes were damaged and uninhabitable, but may be made habitable in a short period of time). Because of the large loss of viable housing, hundreds of people were left without homes. This heightened the urgency to act.

Partly due to cross-organizational relationships developed in the VHP, officials from the City of Minneapolis and various nonprofit groups quickly turned to CURA for help in understanding the extent and location of the tornado damage. Using data gathered from the VHP and other projects, CURA promptly provided maps that indicated--at the parcel level--FEMA's assessment of structural damage, official ownership status (legal rental property or owner-occupied home), and specific repair needs. CURA also provided maps that indicated which of the damaged properties had emergency contact information available. These maps aided the city in prioritizing its outreach efforts and helped nonprofit groups plan their recovery services.

Such a data-mapping request was fulfilled not just because of the relationships CURA had nurtured with various organizations and city and county agencies, but also because of the reputation it had developed as a reliable and trustworthy source of information. Without its history of cooperation and networking, CURA would not have been able to respond in such a constructive way.

Finding and Nurturing Data Sources

Of all of the data sets used in the VHP, the most difficult to obtain is current parcel data, which includes geographic, legal, and zoning information of land and the structures on it. Most municipalities nationwide are beginning to capture this information, and some are even making it available in databases that are accessible to the public, sometimes for a nominal fee but other times for free. Conducting a web search for "parcel data" and a specific geography will typically produce results that can help data seekers identify which government department has the information they require. Parcel data, as well as other data types similar to the indicators above, are available if reciprocal connections are made and nurtured: utility companies have water, electric, and gas information; police have crime reports, including property damage; counties typically have foreclosure data; and detailed MLS data on houses currently on the market are available through a licensed real estate agent. In addition, volunteer-derived data, such as the windshield surveys mentioned earlier, can be created with a little bit of organizing.

Using Data Transparently to Build Trust

To gain regular access to public information without resistance or pushback from those agencies that hold the data, requesting agencies must be up front about their intentions. CURA's role as the go-to place for neighborhood-level data and analysis did not happen overnight; rather, CURA achieved this distinction by continually demonstrating the wide application of data, by maintaining political support for its programs, and by disseminating its research findings to as broad an audience as possible. A key component to this formula is the strong connection of trust that must be built over time, whereby the organization requesting the information must demonstrate that administrative data have a value beyond the simple requirements for which they are collected. That was the case with the water-usage utility data obtained from the city for the VHP: data collected primarily for administrative purposes (i.e., billing residents for water usage) provided valuable secondary benefits as well. These data have not only helped identify vacant houses but have also revealed that a significant portion of water meters are likely malfunctioning--valuable information for city officials. By demonstrating data's usefulness, CURA has established a network of partners that willingly shares data in a reciprocal system that benefits all parties involved.8

Collaborating with Like-Minded Groups

Finally, connecting with other like-minded organizations will greatly expand opportunities and highlight and improve data acquisition and analysis strategies. One particularly powerful resource is the National Neighborhood Indicators Partnership (NNIP), "a collaborative effort by the Urban Institute and local partners to further the development and use of neighborhood-level information systems in local policymaking and community building."9 As previously mentioned, since joining NNIP, CURA staff have connected with and learned from the more than 40 CURA-like centers across the country. These connections have resulted not only in an increased awareness of potential data sources but also of the multiple uses that different data sets can have--educational insights that await anyone who reaches out to other organizations with similar or complementary interests.

About the Authors

Jacob Wascalus is a project manager in the Community Development Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. A graduate of the University of Minnesota's Humphrey School of Public Affairs, he worked for 10 years as a writer, copyeditor, and graphic designer before returning to school to study urban and regional planning.

Jeff Matson is program director of Community GIS (CGIS) at the University of Minnesota's Center for Urban and Regional Affairs. The CGIS program provides mapping, data, and technical assistance to community groups and nonprofits throughout the Twin Cities. Matson received a bachelor's degree in anthropology from the University of California, Berkeley, and a master's degree in Geographic Information Science from the University of Minnesota, where his research focused on environmental justice and public participation GIS.

Michael Grover is the manager of the Community Development Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. His research interests focus on mortgage lending, homeownership, urban development, and community development corporations. Before joining the Minneapolis Fed, Grover worked as a senior labor market analyst for the state of Minnesota's Health and Employment and Economic Development departments. He obtained a PhD in urban studies from the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee in May of 2004. Grover has a BA in history from Saint Cloud State University and an MA in American history from the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee.

1. The Vacant Building Registration program is Minneapolis's primary tool for tracking, monitoring, and managing nuisance vacant properties, and all owners of vacant properties must register and pay an annual fee. For more information about the program, including conditions under which properties may be required to be registered as vacant, see www.ci.minneapolis.mn.us/inspections/ch249list.asp ![]() . Return to text

. Return to text

2. For information on the First Look Program, see www.stabilizationtrust.com/partnerships/hud ![]() . Return to text

. Return to text

3. Includes sale date, estimated market value, owner name, lot size, and property tax assessments, among other categories pertinent to the legal status of land and the structure on it. Return to text

4. For example, CURA participates in the National Neighborhood Indicators Partnership (www2.urban.org/nnip/ ![]() ) coordinated by the Urban Institute. Return to text

) coordinated by the Urban Institute. Return to text

5. Currently, only CURA staff access the VHP spreadsheets and mapping files, and so far the government agencies and neighborhood organizations involved have been satisfied to receive maps, tables, and statistics from CURA upon request. As a result, there are no current plans to create a more interactive or publicly accessible version of the VHP data, but this matter may be reassessed as the users' needs evolve. Return to text

6. At $6,746 per year, Minneapolis levies one of the nation's largest fees on properties that sit vacant for extended periods of time. Return to text

7. Already the new database was put to an unexpected but vital purpose after a tornado struck North Minneapolis in May 2011. As described in box 2, city and county officials, some of whom were involved in the Vacant House Project, turned to CURA and the database to help in organizing and targeting a rapid response to this disaster. Several weeks after the event, other organizations that had previously established relationships with CURA requested information to help in understanding the extent of the damage and to aid in planning their future outreach activities. Return to text

8. Another data-sharing success story occurred a decade earlier when CURA had developed a database and information-sharing structure that assisted Minneapolis neighborhood organizations in detecting properties that were susceptible of abandonment by owners. This early warning system required the collaboration and cooperation of numerous city agencies and neighborhood groups, and it ultimately proved useful to city itself, because the neighborhood residents who had access to the information not only provided feedback on data inaccuracies but relied less on city personnel for information requests. Although the work to create this database of early warning indicators occurred more than 10 years ago, the city continues to use it in a modified form. Return to text

9. See the NNIP website at www2.urban.org/nnip/ ![]() . Return to text

. Return to text