FEDS Notes

December 06, 2024

An Overview of Credit-Building Products

Alexander Bruce and Simona M. Hannon*

Credit-building products are secured small-dollar products that allow consumers to either establish or improve their credit scores by having lenders report their payment activity to credit bureaus. Examples include secured credit cards or loan products such as credit-builder and passbook loans. Despite the potentially significant role that credit building products could play in increasing credit access, relatively little is known about this sector empirically, as data available to researchers to study these products have been historically scarce. In this short analysis, we use a recently released detailed version of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel (CCP)/Equifax credit bureau data to construct measures of key credit-building products—secured credit cards and secured small-dollar loans—to bridge this data gap. In the remainder of this note, we will review the main product types in this sector and use our new data to document developments in this sector since 2010.

Main Product Types

Credit building can be achieved in a number of ways. For example, a consumer can be added as an authorized user on an account in good standing or can use cosigned credit products (Case, 2022). Alternatively, a consumer can make use of various programs that allow the addition of payment history to credit reports or that use bank account information to assess financial behavior.1 That said, the two financial products most central to establishing or improving credit scores are secured credit cards and secured small-dollar loans, which are the focus of the analysis in this note.2

Secured credit cards are credit cards with low credit limits that require a cash deposit usually equal to the credit limit.3 The deposit is used as collateral and the payment history is reported to credit bureaus. Although they are easier to obtain than unsecured credit cards, the annual percentage rate (APR) on these cards may be higher than that on unsecured credit cards (Axelton, 2022).4 These products are primarily offered by large credit card providers (Santucci, 2024).

Secured small-dollar loans consist of either credit-builder loans or passbook loans.5 The key difference between the two secured small-dollar loan types is the ownership of the collateral at issuance, as is discussed next. Credit-builder loans are secured small-dollar products, with origination amounts typically between $300 and $1,000 that are specifically designed for credit building.6 They function less like a loan and more like a (costly) savings device (Burke et al., 2023). Unlike for traditional loans, when the borrower receives the money after application and makes payments to the lender, with a credit-builder loan, the lender deposits the loan amount into a savings account or certificate of deposit (CD) that is held as collateral and is controlled by the lender. The funds become available to the borrower after repayment, which includes the principal and an administrative fee (Burke et al., 2023). Lenders report payment activity to credit bureaus, thus establishing a credit history for the borrower. Credit-builder loans are typically provided by smaller depository institutions, such as credit unions and community banks.7

Passbook loans are secured loans with small origination amounts that are collateralized by a savings account or a CD that is owned by the borrower. They are often used for credit building, but could be used for borrowing purposes unrelated to credit building (Brozic, 2024). They allow borrowers to build credit by having lenders report their payments to credit bureaus. Given their secured nature, passbook loans tend to have lower interest rates than unsecured personal loans (Meacham, 2024). That said, because borrowers own the collateral, they end up paying interest on borrowing their own funds (Bareham, 2024). This cost may be offset to some extent by borrowers earning interest on the funds kept in savings accounts and by avoiding CD withdrawal fees. Similar to credit-builder loans, passbook loans are typically provided by smaller depository institutions— banks and credit unions—as major financial institutions do not offer them (VanSomeren, 2022).8

Data

For the purposes of this analysis, we define credit-building products as those secured credit cards and secured small-dollar loans with a credit limit or an origination amount of $1,000 or less issued by depository institutions—banks, thrifts, and credit unions—to borrowers without credit scores or with nonprime ones.9 To measure these products, similar to other studies examining small-dollar lending in the U.S.—for example, Flagg and Hannon (2024)—we base our analysis on credit card and small-dollar loan holdings reflected in the newly released tradeline-level (or account- or loan-level) version of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York CCP/Equifax data, a database on consumers' credit use and payment performance drawn from anonymized Equifax credit bureau records.10 Our CCP sample has coverage of all credit cards (up to 10 cards per borrower) and all personal loan holdings (up to 4 loans per borrower). The data also contain industry indicators and narrative codes. For credit cards, the industry indicators allow for the categorization of some of the accounts by expenditure sector, or where the cards were used, thus permitting for the elimination of retail credit accounts—see Flagg et al. (2024).11 For loans, the industry indicators allow for the identification of the issuer type: depository institutions—banks, thrifts, and credit unions, and finance companies—personal loan companies, sales finance companies, and a miscellaneous finance company category. The narrative codes offer additional details about each trade, such as whether they are secured. This allows us to isolate secured accounts, which is salient for our analysis. That said, our data do not allow for the separation of credit-builder loans—that are specifically designed for establishing or improving credit—from passbook or other secured small-dollar loans.12 As a result, we have to examine the secured small-dollar loan types together.

As small-dollar products have much lower incidence than other credit product types, to ensure proper coverage, we use the total available nationally representative 5 percent random sample, covering the period between 2010:Q1 and 2024:Q1. As of the beginning of 2024, the CCP loan-level sample showed that over 3 million individuals, or approximately 1 percent of the entire adult population covered by the CCP, had secured small-dollar products.13 93 percent, or 2.8 million, of them are either without credit scores or have nonprime ones. These are the borrowers at the core of this study.

Findings

The credit-building product sector reflected in the CCP data currently stands at $845 million and consists of more than 3 million accounts, with a median origination amount of $500 and a median monthly payment of $26 (Table 1). These accounts are held by typically younger nonprime borrowers, with a median age of 36 and with a median Equifax Risk Score of 604. Borrowers under 40 and deep subprime borrowers each hold more than half of total outstanding balances.14

Table 1: Credit-Building Products Characteristics as of 2024:Q1

| Secured Credit Cards I |

Secured Small-Dollar Loans II |

All Products III |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Outstanding Balance (million $) | 494 | 350 | 845 |

| Number of Accounts (thousands) | 2,316 | 749 | 3,066 |

| Account Size at Origination (median $) | 325 | 724 | 500 |

| Monthly Payment (median $) | 26 | 35 | 26 |

| Borrower Equifax Risk Score (median) | 608 | 576 | 604 |

| Share Balance Deep Subprime (%) | 48 | 54 | 51 |

| Borrower Age (median) | 36 | 34 | 36 |

| Share Balance Borrowers Under 40 (%) | 55 | 66 | 60 |

| Delinquency Rate (%) | 9.5 | 11.2 | 10.2 |

Note: The median Equifax Risk Score in the entire covered population is 743 and the median age is 53. Deep subprime is an Equifax Risk Score below 580. Delinquency measures the fraction of balances that are at least 30 days past due, excluding severe derogatory loans.

Source: Authors' calculations using Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel (CCP)/Equifax.

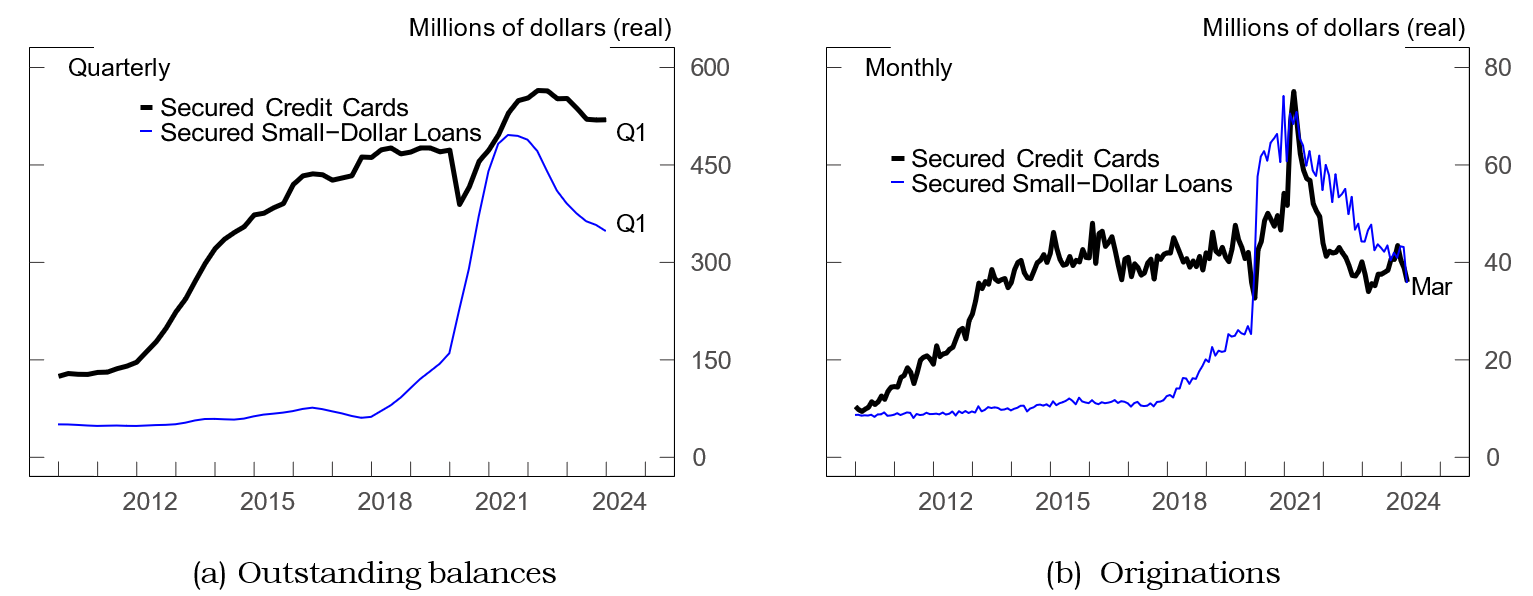

Looking at outstanding balances (Figure 1a) and accounts (Table 1), we note the key role historically played by secured cards within the credit-building product market. Secured cards currently cover 58 percent of balances and 76 percent of accounts, with the remainder consisting of secured small-dollar loans. The median secured card origination amount is $325, with a median monthly payment of $26, while the median secured small-dollar loan has a credit limit of $724 and a monthly payment of $35. Early in 2020, secured credit card outstanding balances (Figure 1a) and originations (Figure 1b) dropped because of a large lender's market exit in 2019, which was followed by the onset of the pandemic (Santucci, 2024). Starting in 2020, originations for both product types rose notably and remained elevated for about two years, before returning close to their pre-pandemic levels by 2024:Q1. Forthcoming analysis attributes the recent increase in credit-building products to fiscal policy effects (Hannon, forthcoming).15

Note: The left panel shows the credit-building outstanding balances by product type. The right panel shows the monthly credit-building issuance by product type. Data are seasonally adjusted.

Source: Authors' calculations using Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel (CCP)/Equifax.

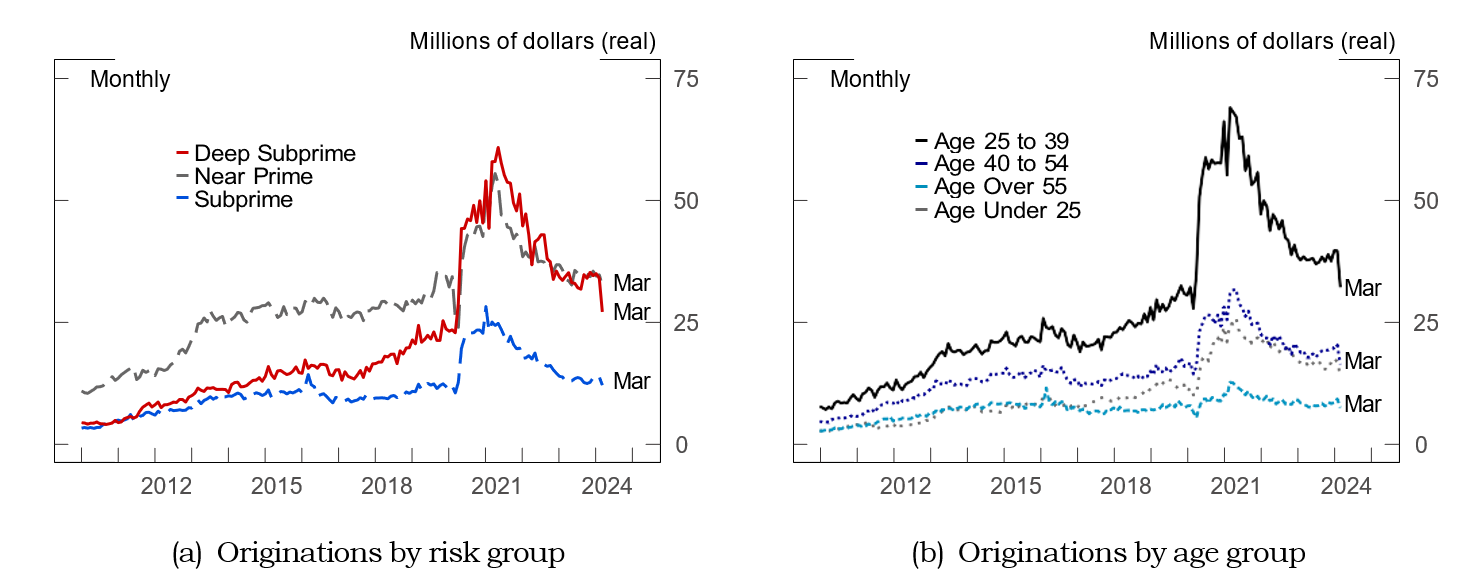

Next, when examining the credit-building sector through the lens of borrowers' credit risk profiles (Table 1), we note differences related to the influence of institutional characteristics on product issuance. Secured cards, typically originated by large credit card providers, as we previously mentioned, are issued to borrowers with slightly higher credit scores than secured small-dollar loans, which are usually offered by smaller lenders, such as credit unions and community banks. The median credit score on a secured credit card account is 608, while the median credit score on a secured small-dollar loan is 576. This trend is further reflected in the shares of balances of each credit-building product type held by deep subprime consumers—approximately 48 percent for secured credit cards and 54 percent for secured small-dollar loans. Looking at originations by credit score for the entire sector (Figure 2a), we note that while originations increased significantly in 2020 and 2021 for all risk groups, they grew most for deep subprime borrowers.

Note: The left panel shows the monthly credit-building issuance by risk group. The right panel shows the monthly credit-building issuance by age group. Data are seasonally adjusted.

Source: Authors' calculations using Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel (CCP)/Equifax.

Looking at the borrowers' ages in the CCP data (Table 1), we find small differences in credit-building product holdings. Secured cards are held by borrowers with a median age of 36, while secured small-dollar loans are held by slightly younger borrowers, with a median age of 34. That said, borrowers under 40 hold different shares of each product type—55 percent of secured credit card balances and 66 percent of secured small-dollar loan balances. Looking at originations by age group across the sector (Figure 2b), we note that while originations for all age groups rose in 2020 and 2021, the majority of the increase is driven by enrollment in credit-building products by borrowers aged 25 to 39.

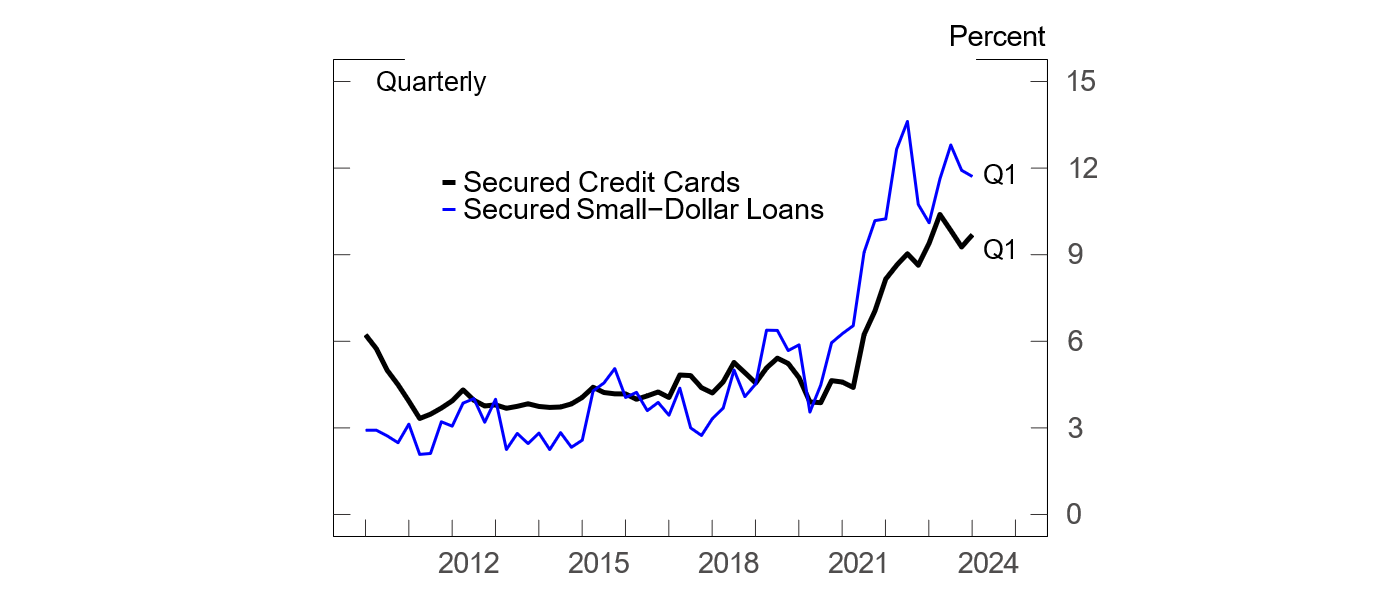

Finally, looking at the credit quality of these products (Table 1), we note that delinquency rates are slightly lower on secured credit card accounts, standing at 9.5 percent, and higher, at 11.2 percent, on secured small-dollar loans. That said, as shown in Figure 3, delinquency rates for both product types have been rising following the pandemic period, in line with those for other loan types.

Note: This figure shows the credit-building delinquency rates by product type. Data are seasonally adjusted.

Source: Authors' calculations using Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel (CCP)/Equifax.

Credit-Building Product Usage Effects

Although credit-building products are expected to contribute to improved credit scores following consistent repayment, the effects of credit-building product usage are only partially known. Some potential downsides associated with the use of such products include borrowers not seeing established or improved credit scores because of lenders not reporting their payment activity to credit bureaus or them defaulting and losing the collateral.

The limited literature on credit-building products provides mixed results. Looking at the universe of secured credit cards reflected in Y-14M data, Santucci (2016) finds that keeping an account open for two years is associated with a 24 point increase in median credit scores.16 Closing the account because of default, however, is associated with a 60 point decrease in median risk scores. For credit-builder loans, a 2020 Consumer Financial Protection Bureau study based on data from three sources finds that, for participants without existing debt, opening a credit-builder loan increased their likelihood of having a credit score 24 percent.17 Additionally, the report shows that participants without existing debt had credit score increases of 60 points relative to their peers with debt. The study also points to a $253 increase in the participants' savings balances. That said, the report also showed results suggesting that consumers had difficulty incorporating additional payments into their obligations—consumers with existing debt saw slight decreases in their scores.18

Conclusion

In this note, we provided an overview of an understudied sector—credit-building products—using a novel version of credit bureau data. The credit-building sector currently stands at $845 million and consists of 3 million accounts held by 2.8 million individuals. From a product perspective, the sector is divided between secured credit cards, which cover nearly 60 percent of outstanding balances, and secured small-dollar loans used for credit building—credit-builder and passbook loans. From an institutional perspective, the sector is segmented between large credit card providers and smaller depository institutions. In 2020 and 2021 the sector experienced an episode of significant growth that is attributed by some studies to fiscal policy effects (Hannon, forthcoming). All credit risk groups exhibited growth, which was driven by enrollment in credit-building products by younger borrowers aged between 25 and 39.

References

Adedoyin, O. (2024). "They Turned 18 and Immediately Had a Credit Score Over 700," https://www.wsj.com/personal-finance/credit/they-turned-18-and-immediately-had-a-credit-score-over-700-9ac55992?mod=Searchresults_pos1&page=1. Wall Street Journal, July 20.

Axelton, K. (2020). "Can I Increase My Credit Limit on a Se- cured Credit Card?" https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/can-i-increase-my-credit-limit-on-a-secured-credit-card/. Experian's Official Credit Advice Blog, September 17.

Axelton, K. (2022). "What Is a Secured Credit Card?" https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/what-is-a-secured-credit-card/. Experian's Official Credit Advice Blog, June 1.

Bareham, H. (2024). "Passbook Loans: Paying to Borrow Your Own Money," https://www.bankrate.com/loans/personal-loans/passbook-loans/. Bankrate, October 18.

Brozic, J. (2024). "4 best secured personal loans" creditkarma https://www.creditkarma.com/personal-loans/i/what-to-know-secured-loan.

Burke, J., J. Jamison, D. Karlan, K. Mihaly, and J. Zinman (2023, 09). "Credit Building or Credit Crumbling? A Credit Builder Loan's Effects on Consumer Behavior and Market Efficiency in the United States". Review of Financial Studies 36(4), 1585–1620.

Case, H. (2022). "Young Borrowers' Usage of Cosigned Credit Cards and Long Run Outcomes," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. July 14, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3165.

Flagg, J. and S. Hannon (2024). "Small-Dollar Loans in the U.S.: Evidence from Credit Bureau Data," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, July 19. https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3571.

Flagg, J., S. Hannon, C. Sarisoy, and M. J. Wicks (2024). "Estimating Retail Credit in the U.S.," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, June 21. .

Hannon, S. "Fiscal Policy and Credit-Building Products," forthcoming.

Heeb, G. (2024). "Credit Scores Without Debt? Fintech Cards Baffle Credit Industry," https://www.wsj.com/finance/credit-score-building-cards-fintech-ea8e61d8?mod=hp_listc_pos3. Wall Street Journal, August 28.

Jayakumar, A. (2024). "Does Experian Boost Strengthen Your Credit?" Nerdwallet https://www.nerdwallet.com/article/finance/experian-boost.

Lee, D. and W. van der Klaauw (2010). "An Introduction To The FRBNY Consumer Credit Panel". Technical report, New York: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, November 10.

Meacham, J. (2024). "Passbook Loan: Meaning, How it Works, Pros and Cons," https://www.investopedia.com/terms/p/passbook-loan.asp. Investopedia, July 21.

Santucci, L. (2016). "The Secured Credit Card Market (PDF)," Discussion Paper Series DP 16-03. Philadelphia: Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, November.

Santucci, L. (2024). "Secured Card Market Update (PDF)," Consumer Finance Institute Special Report. Philadelphia: Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, May.

VanSomeren, L. (2022). "What Is A Passbook Loan?" https://www.forbes.com/advisor/personal-loans/passbook-loan/. Forbes Advisor, November 28.

* We thank Geng Li, Haja Sannoh, and Kamila Sommer helpful comments and suggestions and Aaron Metheny for outstanding editing. The views in this note are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System or its staff.

Alexander Bruce

Address: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 20th Street and Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20551, USA Email: [email protected].

Simona M. Hannon

Address: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 20th Street and Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20551, USA Email: [email protected].

1. For example, Experian offers Experian Boost, a program that adds rent or utility payments to the Experian credit report. Similarly, eCredable Lift uses information from utility accounts and reports it to TransUnion. Experian also offers the UltraFICO score, a program that uses bank account information to assess financial behavior. See Jayakumar (2024) and Adedoyin (2024). Return to text

2. More recently, FinTech companies such as Chime Financial and Credit Sesame, started to offer interest-free credit-builder cards that function very much like debit or secured cards, with the customers depositing money into these accounts and then paying bills or making purchases (Heeb, 2024). However, the full effects of enrollment in these credit-builder card programs still need to be assessed. Return to text

3. The credit limit on a secured credit card can be increased by making an additional deposit or by making a certain number of timely payments (Axelton, 2020). Return to text

4. Secured credit cards usually do not require a credit check (Santucci, 2024). Looking at the universe of secured credit cards, Santucci (2024) shows that the share of secured credit cards with APRs of 25 percent or more has steadily increased since 2015 and stood at 80 percent in 2022. In contrast, interest rate estimates for all credit cards excluding retail accounts that are published in the Federal Reserve Statistical Release G.19, "Consumer Credit" stood at 16.3 percent in 2022. Return to text

5. Passbook loans are also known as share-secured, savings-secured, or savings-pledged loans, among others. See Bareham (2024) and Meacham (2024). Return to text

6. See https://www.equifax.com/personal/education/credit-cards/articles/-/learn/credit-builder-loan/. Return to text

7. See https://www.equifax.com/personal/education/credit-cards/articles/-/learn/credit-builder-loan/. Return to text

8. That said, we identified one large credit union, Navy Federal Credit Union, offering savings-secured loans, but the minimum loan amount started at $25,000, which is outside of the scope of this analysis. See https://www.navyfederal.org/loans-cards/personal-loans.html#PL12. Return to text

9. Nonprime are all borrowers without Equifax Risk Scores and those with ones under 720. Our definition is constructed with the following considerations in mind. First, because credit-building products are collateralized by savings accounts or CDs, we focus on the secured holdings of depository institutions. As of 2024:Q1, the CCP sample reflects nearly $1 billion in secured credit card and more than $63 billion in secured personal loan outstanding balances issued by depository institutions. Second, although both product types can have credit limits or origination amounts of more than $1,000, we limit this study to those products with credit limits or origination amounts of $1,000 or less to capture what we believe are true credit-building products, which are usually thought to be small-dollar products. As of 2024:Q1, these represent 90 percent of secured credit card accounts—accounting for more than half of balances—and more than 20 percent of secured loans—or less than 1 percent of balances. Third, although prime borrowers—those with Equifax Risk Scores of 720 and above—may use secured products, they would likely use them for purposes other than establishing or improving credit. For example, Santucci (2024) notes that a small number of secured credit cards with very high limits may be offered to borrowers who request a credit limit higher than what the lender is willing to offer. As a result, we focus on nonprime borrowers. These borrowers hold the majority of accounts and balances of depository institution-issued secured products with credit limits or origination amounts of $1,000 or less—$484 million in secured credit cards and $344 million in credit-builder loans (Table 1). Return to text

10. The sampling procedure ensures that the same individuals remain in the sample in each quarter and allows for entry into and exit from the sample, so that the sample is representative of the target population in each quarter. See Lee and van der Klaauw (2010) for a description of the design and content of the CCP. See more details on the CCP, available on the Federal Reserve Bank of New York's website at https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/interactives/householdcredit/data/pdf/data_dictionary_HHDC.pdf. Return to text

11. Industry code indicators for the credit card account portion of the data set are only available from 2021:Q4 and onward. The remainder of industry codes in the credit card data are indicative of depository institutions (banks—BB, bank cards—BC, credit unions—FC, savings and loan companies—FS) or credit card companies (ON). The retail credit share observed for the accounts considered in this study is small—less than 3 percent of total outstanding balances and 5 percent of accounts in 2024:Q1. Return to text

12. Following industry agreements between credit-builder loan providers and the three major credit bureaus, credit-builder loans are reported to credit bureaus as traditional installment loans (Burke et al., 2023). Return to text

13. As of 2024:Q1, the CCP covered 289 million individuals—245 million with credit scores. Return to text

14. Deep subprime are considered those borrowers without Equifax Risk Scores or with ones below 580. Return to text

15. For secured credit cards, Santucci (2024) notes that, in 2021, the share of new accounts opened by consumers with- out credit scores deviated from its seasonal pattern of increasing between February and April of each year (that coincides with the post-holiday tax refund season) and remained flat. Santucci (2024) points to stimulus payments and COVID-era benefits easing the budget constraints of consumers without credit scores and allowing them to fund the deposits needed to enroll in secured credit cards and build credit. Return to text

16. In addition to a potential credit score improvement, consistent repayment on a secured credit card may lead to "graduation", which is a transfer to an unsecured card (Santucci, 2024). The FR Y-14M report collects detailed monthly domestic credit card data (among other types of data). The respondent panel is comprised of U.S. bank holding companies, U.S. intermediate holding companies of foreign banking organizations, and covered savings and loan holding companies with $100 billion or more in total consolidated assets (the report is available on the Federal Reserve Board's website at https://www.federalreserve.gov/apps/reportingforms/Report/Index/FR_Y-14M). Return to text

17. See more details on this study, available on the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's website at https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_targeting-credit-builder-loans_report_2020-07.pdf and related paper by Burke et al. (2023). To conduct the study, the CFPB partnered with a Midwestern credit union that already offered a credit-builder loan program. The study combines data from a baseline survey, from credit union administrative systems, and from credit reports. Return to text

18. Thirty-nine percent of participants made at least one late credit-builder loan payment and credit-builder loan usage was associated with increases in late payments on other debt, especially for consumers with previous debt. Return to text

Bruce, Alexander, and Simona M. Hannon (2024). "An Overview of Credit-Building Products," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, December 06, 2024, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3679.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.