FEDS Notes

December 15, 2023

Second-Round Effects of Oil Prices on Inflation in the Advanced Foreign Economies1

Harun Alp, Matthew Klepacz, and Akhil Saxena

Introduction

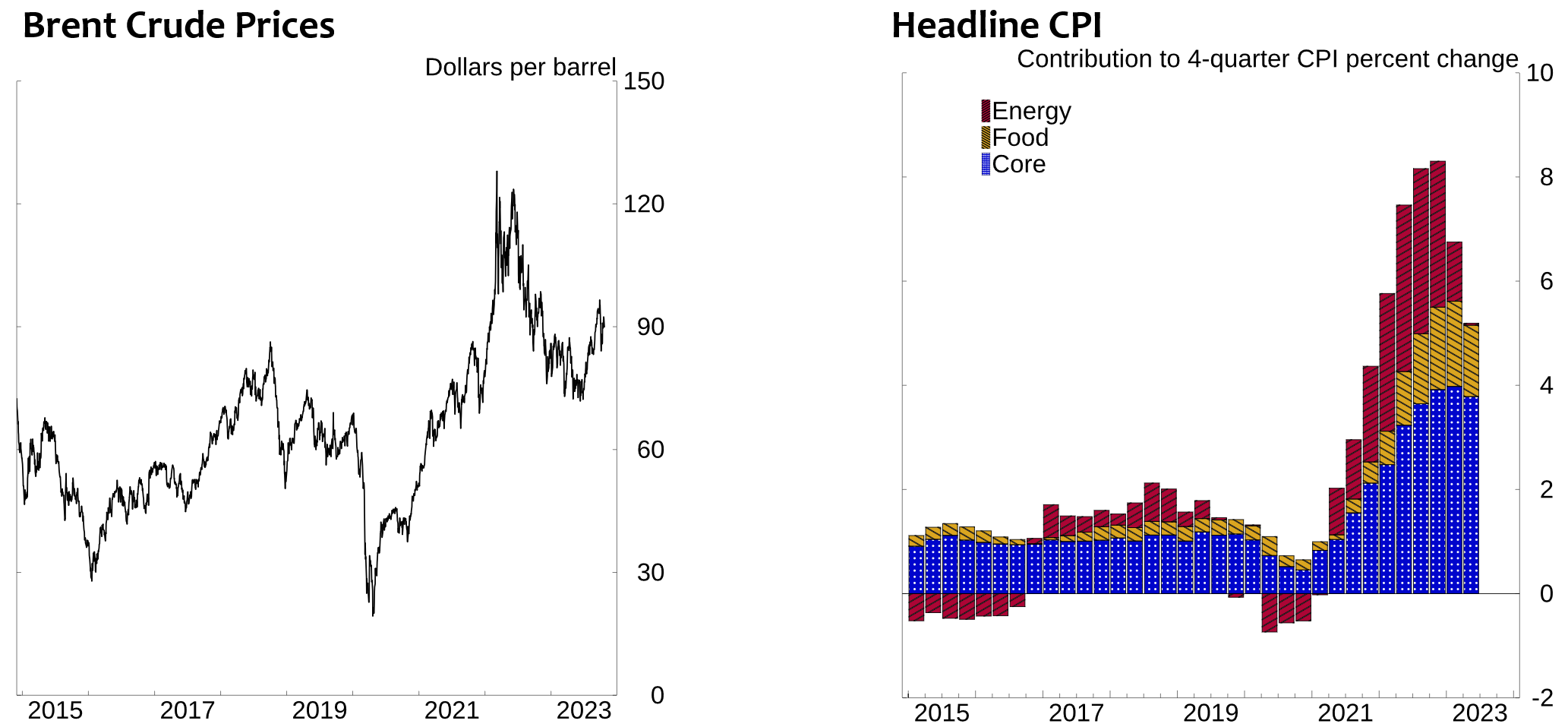

The surge in oil prices in the wake of the post-COVID-19 economic rebound and Russia's invasion of Ukraine exerted significant upward pressure on consumer price inflation around the world. As seen in the left panel of Figure 1, Brent crude oil prices soared to nearly $130 a barrel in March 2022 and remained elevated through June, before only slowly retracing the gains. Since June 2023, prices have begun climbing again. Especially given these large swings in oil prices, assessing the outlook for inflation requires an understanding of how oil price changes can be expected to pass through to inflation.2 In this note, we examine how oil price changes pass-through to inflation in selected advanced economies (Canada, the U.K., and the euro area). We find that oil price pass-through to inflation is both economically and statistically significant, and that it occurs both directly and through second-round effects.

The right panel of Figure 1 decomposes the four-quarter headline inflation rates for the selected economies into the contributions of energy, food, and core prices. The red portions of the bars highlight the sizable contribution of the energy component of the CPI to overall inflation in recent years. These portions do not capture the total contribution of oil prices to headline inflation, however, because they do not include the indirect effects – so-called second round effects – of higher energy to food and core prices. For example, higher oil prices drive up production and transportation costs throughout the economy, which are then passed through to food and core prices. Higher energy prices can also raise consumer and business expectations for future inflation, indirectly raising food and core prices now.

Note: Aggregate represents the trade-weighted average of euro-area, Canada, and U.K. consumer price index (CPI) inflation.

Source: Office for National Statistics, Statistics Canada, Eurostat, Bureau of Economic Analysis all via Haver Analytics; Bloomberg Finance LP, Bloomberg Commodity Prices; authors' calculations

This note aims to quantify the magnitude and persistence of these second-round effects to then compute the overall effect of energy prices on inflation. We use an empirical model on panel data (with the panel consisting of time-series data on a cross-section of 27 advanced economies) to estimate the average dynamic effect of a 10 percent increase in the price of Brent crude oil on the food and core components of inflation. We find statistically significant second-round effects, although they are not large, with larger pass-through to food prices than to core prices. Pass-through is gradual but long-lasting, with the effect building over about 8 quarters after the oil price increase. Our estimates also imply that second-round effects of past oil price changes have raised four-quarter aggregate headline inflation in the selected economies by 0.5 percentage points on average since the fourth quarter of 2022, contributing to high inflation in these economies. Our model estimates also imply that the second-round effects of the recent rally in Brent prices in the third quarter of 2023 may be expected to exert some upward pressure on inflation as far out as mid-2025, potentially slowing the disinflation process in train.

Methodology

To fully account for the contribution of oil prices to headline inflation, we use an empirical model that can identify the dynamic response of each of the components of the CPI to changes in Brent crude oil prices.3 We use quarterly data from 2000 through 2022 for 27 selected advanced economies to estimate the pass-through to inflation. Taking account of the cross-country variability allows us to derive fairly precise estimates, even though the individual country time-series data are rather noisy. For different choices of the horizon, denoted by h, we estimate the following equation:

ΔhpCompj,t+h=αj+8∑k=0βCompk,hΔpOilt−k+8∑k=1γCompk,hΔpCompj,t−k+8∑k=0ϕCompk,hΔFXj,t−k+8∑k=0κCompk,hREAt−k

+8∑k=0χCompk,hΔUNj,t−k+μComphI(COVID)+ϵCompj,t+h

where ΔhpCompj,t+h is the cumulative change in the log price level for country j for the food, core, or energy component, h quarters ahead. Our coefficients of interest are βComp0,h, which trace the cumulative effect of an observed log Brent price change, ΔpOilt, from time t to time t+h, for each component of inflation. We include as controls 8 lags of past changes in oil prices and past changes in the price level component of interest. Additional controls include contemporaneous and 8 lagged values of the change in the dollar exchange rate ΔFXj,t, since oil is generally priced in dollars, the global real economic activity index constructed in Kilian (2009) REAt, to control for demand for industrial commodities in global markets, as well as the change in the country-level unemployment rate ΔUNj,t, to account for local economic activity. We include country fixed effects and a COVID dummy variable, which encompasses all years in the sample from 2020 on, to allow for COVID-specific inflation effects. Our analysis takes a similar approach to other studies examining the pass-through of energy prices to inflation.4

We use country weights in the regressions, constructed in two steps: first computing the U.S. trade weight for Canada, the U.K., and the European Union as a whole and further dividing the EU weight between countries based on their respective PPP-GDP shares. We then use these estimated impulse responses to determine how past movements in oil prices have contributed to inflation dynamics by calculating the increase in inflation implied by our estimates.

Results

Based on our cross-country panel results, we begin by calculating the effect of a 10 percent permanent immediate increase in oil prices on energy, food, and core inflation. Figure 2 shows the estimated cumulative percent change in the levels of the energy, food, and core consumer price indices in response to such a change in global energy prices. This increase in the price of oil raises the energy CPI itself by 2.3 percent after two quarters, and the energy CPI remains relatively stable and elevated through the rest of the horizon. As expected, the pass-through of the oil price increase to other components, both food and core, is smaller but still statistically significant, with the total effects reaching 0.3 percent for the food CPI and 0.1 percent for the core CPI. Pass-through to both components is slow but long lasting, with the effect building over about eight quarters after the oil price increase. Taking into account the relative importance of food and core products in the overall CPI basket, our analysis suggests that the second-round effects of a 10 percent increase in oil prices would raise headline CPI by almost 0.15 percent at its peak. Including the effect on the energy CPI, a 10 percent increase in the price of oil raises headline CPI by almost 0.4 percent in total.

Note: Assumes a 10 percent permanent increase in the price of crude oil. Dashed lines show 95 percent confidence intervals based on robust standard errors, clustered at the country level.

Source: Office for National Statistics, Statistics Canada, Eurostat, Bureau of Economic Analysis all via Haver Analytics; Bloomberg Finance LP, Bloomberg Commodity Prices; Kilian (2009); authors' calculations.

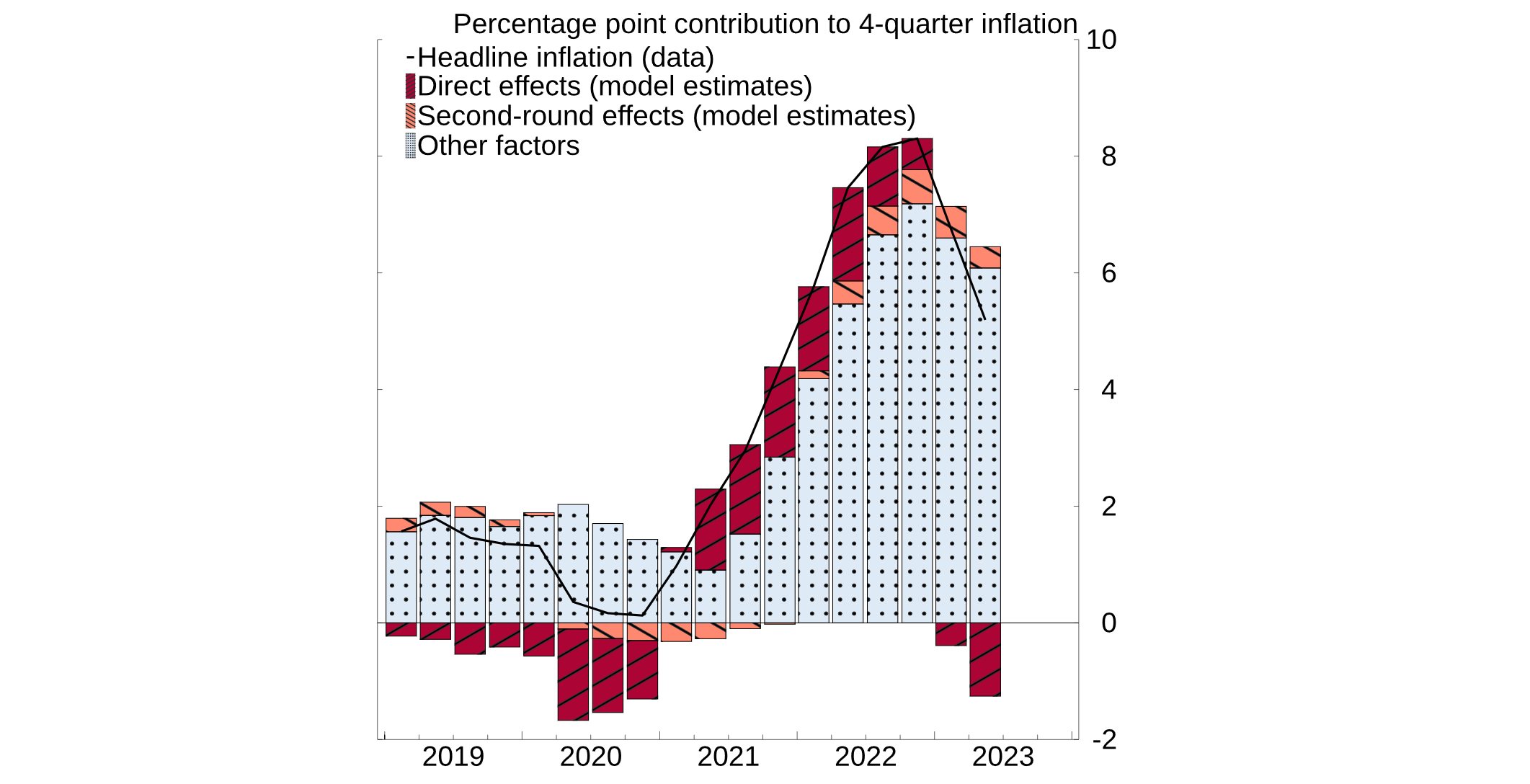

Building on this result, we next calculate pass-through to inflation conditional on the observed large swings in oil prices in recent years. The implied second-round effects have economically meaningful implications for headline inflation. To see these implications, figure 3 decomposes the contributions of energy price movements into direct effects, estimated using the pass-through coefficients from an oil shock to energy CPI, and second-round effects, estimated using the pass-through coefficients for the food and core CPIs. The run-up in oil prices has markedly driven up headline inflation in our selected advanced economies since late 2021 both directly, through a substantial rapid increase in energy CPI, and indirectly, through somewhat smaller and delayed second-round effects on food and core CPIs. Although the direct effects generally account for a greater share of the oil contribution (1.1 percentage points on average from the start of 2021 through the end of 2022), the second-round effects are still sizable, contributing 0.5 percentage points to four-quarter headline inflation on average since the fourth quarter of 2022.

Note: Black line represents data for the trade-weighted average of euro-area, Canada, and U.K. headline inflation.

Source: Office for National Statistics, Statistics Canada, Eurostat, Bureau of Economic Analysis all via Haver Analytics; authors' calculations; authors' calculations

Our estimates also suggest that second-round effects will continue to play a role in inflation dynamics in the coming years. Assuming oil prices remain at the level observed in the third quarter of 2023, our model estimates imply second-round effects of past increases in oil prices are expected to boost four-quarter inflation in the selected advanced economies through the first quarter of 2024 before contributing to disinflation for the rest of 2024 reflecting the fall in oil prices earlier this year and much of last year. However, the second-round effects turn positive again in the second quarter of 2025, reflecting the long lags with which the most recent increase in prices since July 2023 of this year can be expected to pass through to food and core prices.

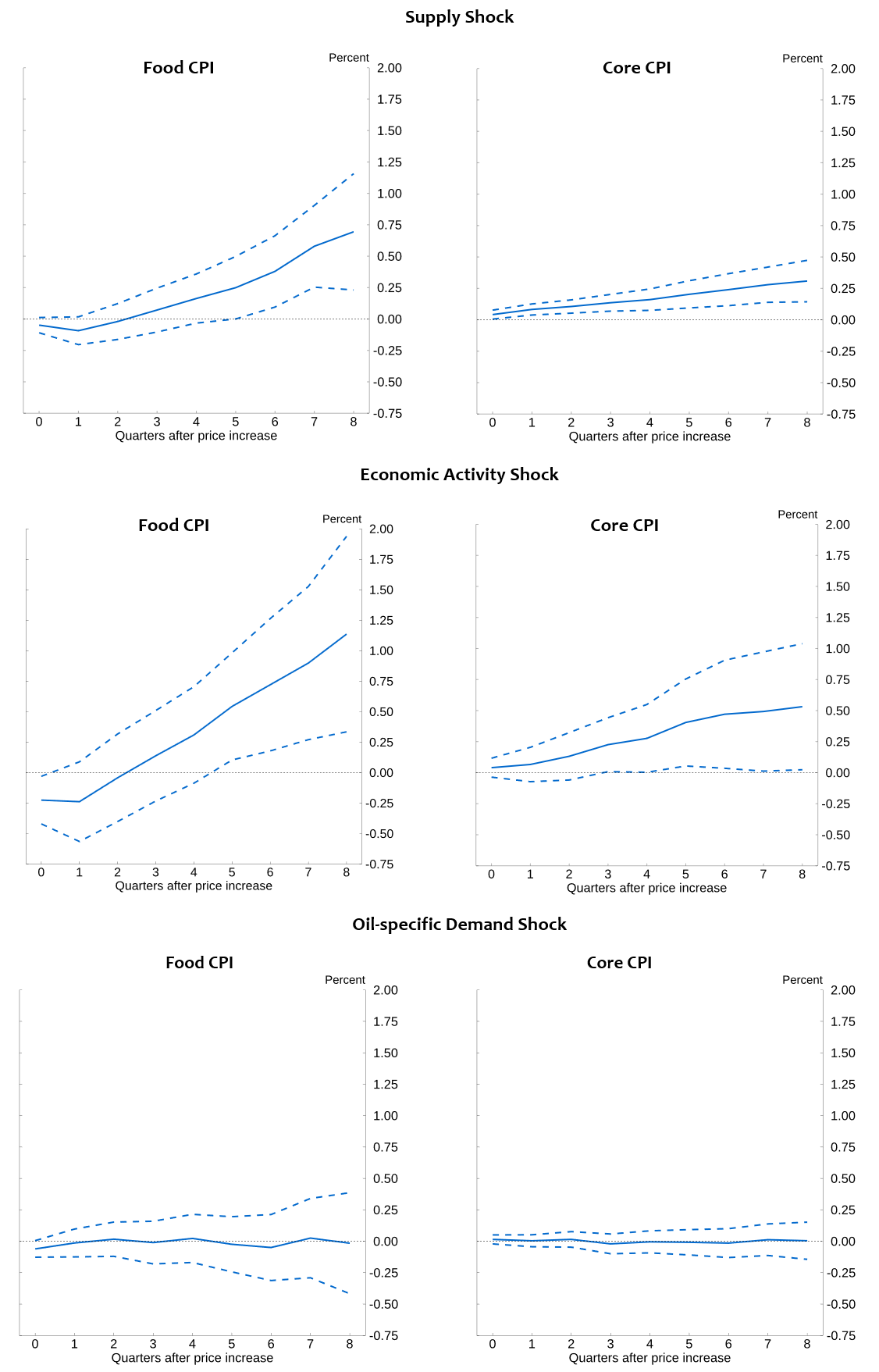

Our baseline specification examines the pass-through of a realized change in oil prices to country-level inflation components. This approach relies on the assumption that these changes are exogeneous to country-level factors conditional on the included controls. As an additional robustness check, we examine how our estimated effects change when observed price changes are instrumented with identified shocks from a structural model of the oil market. We use the shocks from Baumeister and Hamilton (2019), which decomposes oil price changes into movements attributable to supply shocks, global economic activity shocks, oil-specific demand shocks, and inventory demand shocks. Thus, this approach allows us to look at the different effects of each of these factors driving oil prices. We estimate the same equation as above, but instrument for the change in the Brent price using the shock of interest. The estimated impulse responses can therefore be interpreted as the effect on inflation of a 10 percent increase in the price of oil attributable to a given shock.

Figure 4 displays the results of this estimation. Pass-through to food and core is significant in response to a supply shock and global economic activity shock, but not an oil-specific demand shock. The responses to a 10 percent increase in prices due to the supply and global economic activity shocks are larger than in the response in the baseline specification, and an increase in oil prices due to a global economic activity shock passes through to food and core more strongly than one due to a supply shock. This could be attributable to the greater persistence of the activity shock's effect on oil prices when compared to the supply and oil-specific demand shock.

Note: Assumes a 10 percent permanent increase in the price of crude oil due to the specified identified shock. Dashed lines show 95 percent confidence intervals.

Source: Office for National Statistics, Statistics Canada, Eurostat, Bureau of Economic Analysis all via Haver Analytics; Bloomberg Finance LP, Bloomberg Commodity Prices; Kilian (2009); Baumeister and Hamilton (2019); authors' calculations.

In summary, our analysis suggests that increases in oil prices lead to small but significant second-round effects on inflation through their pass-through to food and core prices, and that these effects operate with long lags. Our model estimates suggest that the second-round effects of past oil price increases have raised four-quarter headline inflation in selected advanced economies by 0.5 percentage points on average since the fourth quarter of 2022, and can be expected to boost headline inflation as far away as 2025. Our results indicate that oil prices will continue to play an important role in inflationary dynamics for the foreseeable future.

References:

Baba, Chikako and Jaewoo Lee. 2022. "Second-Round Effects of Oil Price Shocks: Implications for Europe's Inflation Outlook." IMF Working Papers, 2022(173).

Baumeister, Christiane. 2023. "Pandemic, War, Inflation: Oil Markets at a Crossroads." NBER Working Paper Series, 31496, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Baumeister, Christiane, and James D. Hamilton. 2019. "Structural Interpretation of Vector Autoregressions with Incomplete Identification: Revisiting the Role of Oil Supply and Demand Shocks." American Economic Review, 109 (5): 1873-1910.

Choi, Sangyup, Davide Furceri, Prakash Loungani, Saurab Mishra, and Marcos Poplawski-Ribeiro. 2018. "Oil prices and inflation dynamics: Evidence from advanced and developing economies." Journal of International Money and Finance, 82: 71-96.

Kilian, Lutz. 2009. "Not All Oil Price Shocks Are Alike: Disentangling Demand and Supply Shocks in the Crude Oil Market." American Economic Review, 99 (3): 1053-69.

Kilian, Lutz and Xiaoqing Zhou. 2023. "A Broader Perspective on the Inflationary Effects of Energy Price Shocks." Energy Economics, 125, 106893.

1. The views in this note are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System or of any other person associated with the Federal Reserve System. We thank Deepa Datta, Andrea De Michelis, Logan Lewis, and the members of the International Finance Division for their comments and suggestions. Return to text

2. Kilian and Zhou (2023) investigate the effect of gasoline price increases on inflation and find that gasoline price increases had a modest effect on headline inflation and little effect on core in the U.S., while the pass-through is greater in the euro area. Baumeister (2023) also examines the role of oil price shocks in boosting European and U.S. inflation and finds evidence of greater persistence in Europe. Return to text

3. Our empirical strategy utilizes the often-used local projections approach. Return to text

4. Choi et al. (2018) apply a panel local projections approach to a dataset of 72 advanced and developing economies from 1970 to 2015 and find that a 10 percent increase in the price of crude oil raises headline inflation by 0.4 percentage points on impact, with the effect moderating over two years. Similarly, Baba and Lee (2022) employ panel local projections to study how oil price shocks pass-through to wage growth, and find that a 1 percent increase in oil prices raises wages by about 0.025 percent a year after the shock. Return to text

Alp, Harun, Matthew Klepacz, and Akhil Saxena (2023). "Second-Round Effects of Oil Prices on Inflation in the Advanced Foreign Economies," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, December 15, 2023, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3401.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board staff offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers and IFDP papers.