FEDS Notes

December 1, 2016

Holiday Spending and Financing Decisions in the 2015 Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking

Jeff Larrimore

One of the recurring themes in the Federal Reserve Board's Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED) is a lack of savings capacity for many individuals. This was manifested in the 2015 survey by the nearly half of respondents who would borrow or sell something to cover a $400 emergency expense (Federal Reserve Board, 2016). However, while preparing for unexpected emergencies is an important aspect of savings, it represents only one dimension of how individuals plan for future needs and expenses. Individuals also regularly make many smaller scale savings decisions for upcoming known expenses with shorter time horizons, and may prepare for these types of expenses differently than they do for unknown financial emergencies.

The idea of distinct savings motives has been long noted by researchers, including by Keynes (1936) who outlined eight separate motives for savings. Keynes' framework included "to build up a reserve against unforeseen contingencies" and "to provide for an anticipated future relationship between the income and needs of the individual" as two separate motivations (see Browning and Lusardi, 1996, for a summary of all eight of Keynes' motives, as well as a discussion of the savings motives). The responses to the $400 emergency expense question in the SHED provides information on rainy day savings for an unforeseen contingency. In order to also understand savings for anticipated future needs – which we refer to here as "circumstantial savings"' using the terminology of Rowlingson et al. (1999) – the 2015 SHED included a set of questions on holiday spending and financing.1 Holiday spending is advantageous for considering circumstantial savings, as it represents a specific anticipated expense, but it is also an expense that often requires some level of advanced planning in order to spend without borrowing.

In addition to providing information on the frequency of circumstantial savings, the holiday spending questions yield information on how non-savers manage discretionary spending choices. In particular, individuals without short-term circumstantial savings for the holidays may choose to forgo spending or may plan to spend through borrowing. Among those who spend through borrowing, they then also face decisions regarding how long to carry the debt. Consistent with the pattern across income levels for emergency rainy day savings, there is evidence from the survey that lower income respondents were less likely to have sufficient savings set aside to cover holiday spending without borrowing. However, we also observe that while higher income respondents with a holiday savings shortfall often made up for it by borrowing, lower income respondents made up for it by forgoing their holiday spending.

Summary Statistics on Holiday Spending and Borrowing

In the fall 2015 SHED, which was fielded from October 30 through November 24, the vast majority of U.S. adults reported that they were planning to spend at least some money on holiday gifts in the coming months (i.e. late 2015), with 77 percent indicating that they planned to purchase gifts. This holiday spending represented a non-trivial financial expense. Among those who expected to spend money on holiday gifts, the mean expected spending was $728 (median of $500). Hence, the median holiday spending was just under 1% of median annual household income, which was $56,516 in 2015 (Proctor, Semega, and Kollar, 2016), and it represented a larger share of disposable income.2

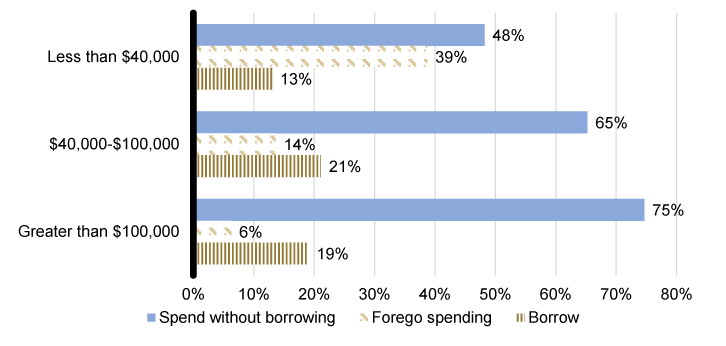

Although some individuals borrow for the holidays, a majority of those who planned to spend money on holiday gifts expected to do so without borrowing. Specifically, 78 percent of all adults who were buying gifts (60 percent of all adults, including those who are not buying gifts) did not anticipate using any borrowing to finance their spending.3 Furthermore, among those who planned to borrow, half indicated that they expected to pay off that debt within three months. There was, however, a sizeable minority of borrowers who expected to carry the debt into the following summer or beyond, including 13 percent who expected to be carrying the debt for a year or longer (Figure 1).

|

|

Note: Among respondents who plan to use a credit card that is paid off over time, a layaway plan, a loan, or any other form of borrowing to pay for holiday gifts.

Holiday Spending and Borrowing by Income

The approaches to holiday spending in the SHED data can be subdivided into three mutually exclusive categories, which reflect each individual's saving and spending decisions. The first is to spend on holiday gifts without borrowing. This approach requires either establishing circumstantial savings to pay for holiday gifts, having flexibility in one's monthly budget to fund gifts using ordinary monthly income, or earning additional income in the final months of the year through seasonal employment or bonuses. Overall, 60 percent of adults planned to spend on holiday gifts without borrowing. This compares to the 54 percent of adults who said that they would pay for a $400 emergency expense without borrowing.

The second potential avenue for approaching holiday spending, which is available to those who did not set aside circumstantial savings for their holiday spending needs, is to spend on holiday gifts using some form of borrowing that is then paid off over time. This may involve short-term borrowing, which is paid off relatively quickly after the holidays, or longer term borrowing, which the individual carries well into the following year. Seventeen percent of adults planned to spend on holiday gifts and use some amount of borrowing to do so.

In contrast to a true emergency expense, which may be unavoidable, there is also a third possible avenue for discretionary holiday spending. This is to forgo spending entirely (or reduce the level of spending). For some individuals the choice to not spend on holiday gifts reflects religious preferences or family traditions, but for others it reflects a financial choice or necessity. Among those who do not have the desire or capacity for circumstantial saving through the year, and who cannot fund holiday spending entirely using their end-of-year income, forgoing spending represents a potential alternative to incurring debt for such purchases. Twenty-three percent of adults reported that they were not planning to spend any money on holiday gifts.

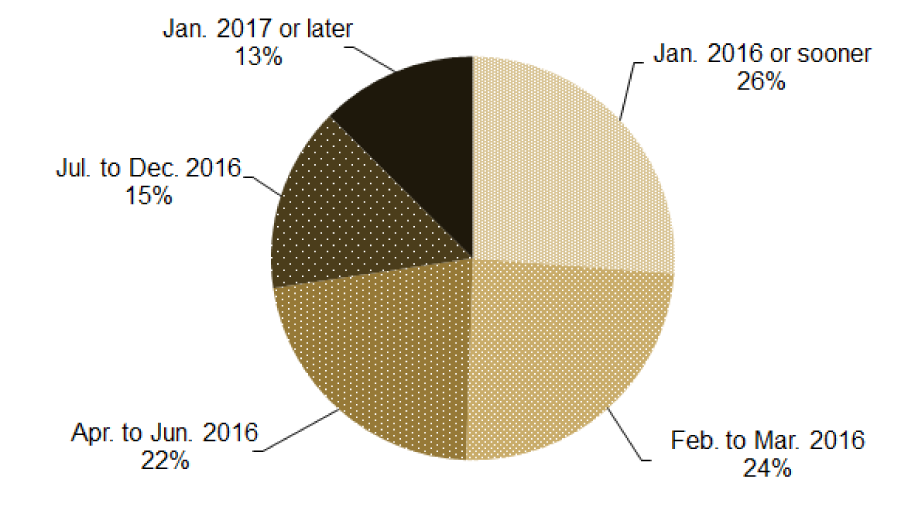

Figure 2 illustrates the frequency of these three potential approaches to holiday spending based on the income of the respondent and his or her spouse or partner. Reflecting the increased financial flexibility and savings capacity of high income individuals, the likelihood of purchasing holiday gifts without borrowing increases markedly with family income. Among those whose family income was under $40,000, only 48 percent of respondents indicated that they would purchase holiday gifts without borrowing. This increased to 75 percent of those with family incomes over $100,000.

The lower-income respondents who were not purchasing holiday gifts using cash-on-hand, however, generally did not turn to borrowing in order to fund holiday purchases. Instead, lower income respondents who were unable to afford holiday spending without borrowing opted to forgo holiday spending at a greater frequency than their high income counterparts. For those whose family income was less than $40,000, 39 percent planned to spend nothing on holiday gifts in 2015. This compares to 14 percent of those whose income is between $40,000 and $100,000 and 6 percent of those with an income greater than $100,000 who planned to not spend on holiday gifts. In contrast, just 13 percent of respondents in the lowest income group reported that they would borrow to finance their holiday gifts, which is below that seen among either of the higher income groups.

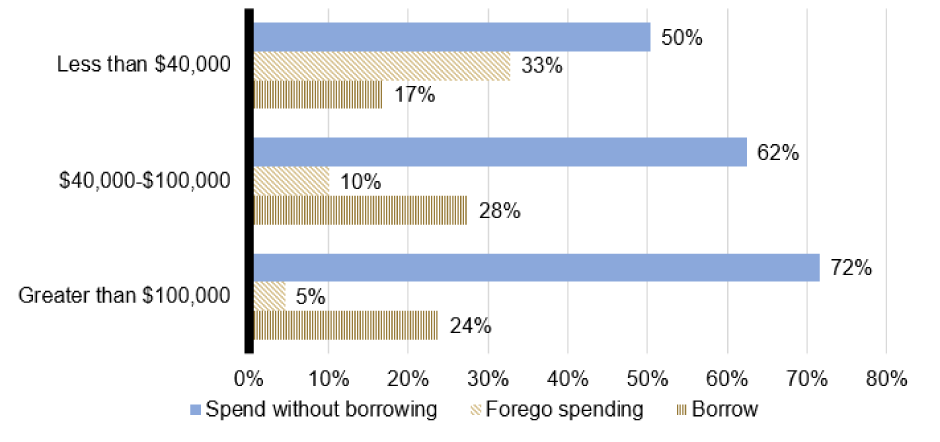

One may expect that how individuals approach holiday spending could differ for parents, as having children can shift the perceived importance of holiday gift giving. To address this possibility, Figure 3 repeats the comparison above, but does so only for parents living with their children. Within each income group, the likelihood of forgoing spending was lower for parents than it was for the overall adult population with similar incomes. Furthermore, the likelihood of borrowing to finance that spending was higher. However, the pattern of borrowing across income classes is unchanged. Once again, the frequency of holiday spending rises with income, and lower-income respondents who could not pay out of pocket disproportionately reported that they would not spend at all whereas higher-income respondents who could not pay out of pocket instead disproportionately turned to borrowing.

|

|

Having separated individuals' approaches to holiday spending into these categories, we can explore how circumstantial savings and plans for holiday spending differ for those who are, or are not, prepared for a modest unexpected emergency. In particular, are individuals who appear well prepared for a $400 emergency out of their rainy day savings also better positioned to cover their holiday spending out of their circumstantial savings?

Overall, 46 percent of survey respondents indicated that they either could not pay a $400 emergency expense, or that they would borrow or sell something to do so. This compares to the 40 percent of respondents who said that they would not spend anything on the holidays or were going to borrow to do so. An additional 25 percent of adults were planning to spend money on holiday gifts without borrowing, but planned to spend under $400. These individuals who were spending lower amounts are separated out here, since the lower level of holiday spending could stem either from financial restraint or from a lack of savings.

Table 1 considers the correlation between preparedness for a $400 emergency expense and how individuals plan to spend and borrow for the holidays. As one may expect, there is a substantial overlap between those with rainy day savings and those who seem to have circumstantial savings for the holidays. Among respondents who would not pay a $400 emergency expense using cash or its equivalent, 57 percent also planned to either borrow for the holidays or forgo spending (and an additional 26 percent planned to not borrow, but spend less than $400 on the holidays). In contrast, among respondents who indicated that they were well prepared for a $400 emergency expense, just over half reported that they would spend at least $400 on the holidays without borrowing.

| Borrow, sell something, or could not pay $400 emergency expense | Cover $400 emergency expense without borrowing | |

|---|---|---|

| Forgo holiday spending | 34.5 | 12.7 |

| Borrow for holiday spending | 22.2 | 12.9 |

| No borrowing - spend under $400 | 26.4 | 23.9 |

| No borrowing - spend at least $400 | 16.9 | 50.6 |

However, we also observe that 17 percent of those who exhibited some difficulty with a $400 emergency expense were planning to spend at least $400 on holiday gifts without borrowing. This may indicate that these individuals have found the ability to establish circumstantial savings even if they do not have precautionary rainy day savings. Alternatively, it may reflect differences in timing of when funds are needed, as some people will take on seasonal employment or will cut back on other non-holiday related discretionary spending to pay holiday bills.

Conversely, among those who seem prepared for a modest emergency expense – and would cover a $400 emergency expense without borrowing – approximately one-quarter indicate a limited degree of circumstantial savings either by forgoing holiday spending or by borrowing to cover their expenses. Of particular interest is the 13 percent of respondents who explicitly indicate that they will cover a $400 emergency expense without borrowing, but report that they will make holiday purchases using borrowing. This behavior is suggestive of financial compartmentalization where individuals earmark funds for a specific purpose (such as an emergency), and will borrow for other purposes to avoid touching those funds. While seemingly contradictory, this behavior is consistent with Sussman and O'Brien's (Forthcoming) findings that that individuals have an aversion to touch earmarked funds even when the alternative to using those funds is to borrow money from high interest rate credit options.

The relationship between these two sets of questions also provides insight into the spending decisions of individuals at different income levels who each would struggle with the modest emergency. Irrespective of the income level, over half of those who would struggle with a $400 emergency expense reported that they planned to borrow for the holidays or not spend. But, their alternative approach to the holidays differs by income. Among those making under $40,000 who would borrow or sell something to cover an emergency expense, 46 percent were not spending money on the holidays whereas 14 percent were borrowing to pay their holiday bills. These results are nearly reversed among those with over $100,000 of income with a similar lack of emergency savings. Forty percent of this higher income group planned to borrow for their holiday spending whereas just 12 percent planned to forgo spending.

Credit Supply Constraints or Credit Demand

Recognizing that lower-income individuals had a lower frequency of borrowing for holiday spending than those higher in the income distribution – including among those with similar levels of preparedness for a modest emergency – it raises the question of why these differences arise. It may reflect a level of financial restraint, as lower income individuals more clearly recognized the limits of their disposable income. However, it may also reflect limited access to credit among this population, which restricted their ability to borrow during the holidays.

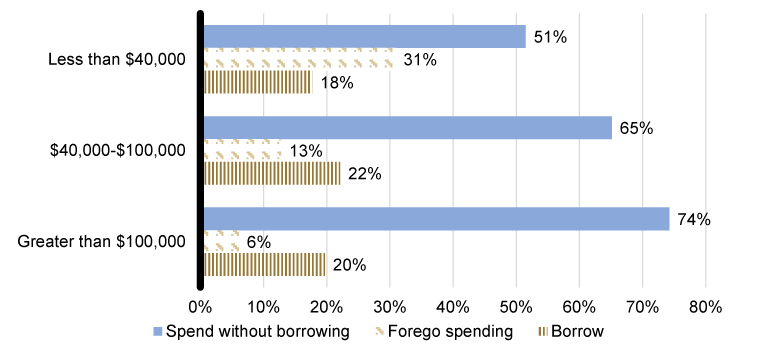

In order to control for differences in credit access by income, Figure 4 considers only those respondents who either have a credit card or are very confident that they would be approved for a credit card were they to apply for one.4 When doing so, it appears that credit supply constraints contribute to the lower rate of borrowing for the holidays among low income respondents. Eighteen percent of these lower-income respondents with access to credit planned to borrow for the holiday – compared to the 13 percent of all adults in this income group in Figure 2 who planned to borrow. However, even when focusing only on respondents who were most likely to have access to credit, the fraction of lower-income respondents who planned to borrow is below that seen among their higher-income counterparts. Furthermore, it remained more common for these lower-income respondents with access to credit to indicate that they would not purchase holiday gifts (31%) than it was for them to indicate that they would finance holiday spending through borrowing (18%).

|

|

The impact of income on one's propensity to borrow for holiday spending can be more formally observed using a Probit regression that regresses borrowing for holiday spending on the consumer's income, access, to credit, and demographic characteristics. When doing so, in Table 2, it is apparent that those who had access to credit were substantially more likely to borrow than those who did not. It also corroborates the income patterns seen in the above figures. When controlling for credit access and other demographic characteristics, those in the lowest income group were significantly less likely to borrow than were middle-income respondents (and less likely to borrow, but not to a significant degree, than high-income respondents). This suggests that at least part of the lower rates of borrowing for these expenses among low income individuals is reflective of a choice to limit spending rather than being purely a reflection of limits to their access to credit.

| Income $40,000-$100,000 | 0.187*** |

|---|---|

| (0.07) | |

| Income greater than $100,000 | 0.046 |

| (0.08) | |

| Confident in credit access | 0.701*** |

| (0.09) | |

| Parent living with children | 0.216*** |

| (0.07) | |

| Gender - Female | 0.088* |

| (0.05) |

Note: regression includes additional controls for race/ethnicity, marital status, age, geographic Census region, and MSA status. The omitted income category is respondents with an income of less than $40,000. Standard errors in parentheses.

***Significant at the 1% level Return to table, **Significant at the 5% level, *Significant at the 10% level Return to table.

Conclusion

While a substantial majority of adults planned to spend money on the holidays, the likelihood of spending and the way that spending is financed varies greatly by income. Lower income adults appear less likely than those higher in the income distribution to have established circumstantial savings – as evidenced by their higher frequency of either borrowing for the holidays or foregoing spending completely. However, while they often appear to lack the capacity to spend on the holidays without borrowing, these lower income adults often opt to forego spending completely rather than take on debt to finance their holiday purchases.

These observations about holiday spending also provide insights into the different financial decisions across income levels of those who lack rainy day savings. While individuals at each income level who exhibit some difficulty with a modest emergency expense are similarly likely to be unable to fund holiday spending without borrowing, lower income respondents without emergency savings generally report that they will not spend on the holidays whereas higher income respondents without emergency savings often report that they will borrow to cover their holiday spending. This distinction suggests that those lacking emergency savings are not a homogenous group and indicates that further research considering the barriers for specific individuals to saving for emergencies is warranted.

References

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2016. Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2015.

Browning, Martin and Annamaria Lusardi. 1996. "Household Saving: Micro Theories and Micro Facts" Journal of Economic Literature 34(4): 1797-1855.

Census Bureau. 2016. Monthly Retail Trade Survey Historical Data: Retail and Food Service Sales. Retrieved October 13, 2016 from https://www.census.gov/retail/mrts/historic_releases.html

Kempson, Elaine and Andrea Finney. "Saving in lower-income households: A review of the evidence" Personal Finance Research Centre, University of Bristol. Accessed via: http://www.pfrc.bris.ac.uk/completed_research/Reports/2009_6_FITF_Saving.pdf

Keynes, John Maynard. 1936. The general theory of employment, interest, and money. London: MacMillan.

National Retail Federation. 2015. Holiday Trends and Expectations. Retrieved October 13, 2016 from https://nrf.com/sites/default/files/Images/Media%20Center/2015%20NRF%20HSK_Final_Small.pdf

Proctor, Bernadette D., Jessica L. Semega, and Melissa A. Kollar. 2016. "Income and Poverty in the United States: 2015." U.S. Census Bureau Population reports P60-256.

Rowlingson, Karen, Claire Whyley, and Tracey Warren. 1999. "Income, wealth and the lifecycle" London: Policy Studies Institute.

Sussman, Abigail B. and Rourke L. O'Brien. Forthcoming. "Knowing when to spend: Unintended financial consequences of earmarking to encourage savings" Journal of Marketing Research.

1. There is no universally accepted term for this form of savings. For example, Kempson and Finney (2009) refer to them as instrumental savings and Browning and Lusardi (1996), focusing on longer-term anticipated future needs, refer to them as life-cycle motive savings. Return to text

2. For comparison of the spending estimates in the SHED to other data, the National Retail Federation (NRF) survey in the fall of 2015 projected average holiday spending of $805.65 in 2015 (National Retail Federation 2015). Reflecting the importance of holiday spending to retail sales, according to the US Census Monthly Retail Trade Survey, total monthly retail sales (excluding food service, motor vehicles, and parts) in December of 2015 exceeded the average monthly retail sales in the other 11 months of 2015 by $79 billion (Census Bureau 2016). Return to text

3. The question on financing holiday spending asks respondents whether they plan to use "a credit card that you pay off over time, a layaway plan, a loan, or any other form of borrowing." Return to text

4. Almost all individuals who are very confident that they would be approved for a credit card have one, so 96 percent of those who are considered to have access to credit under this criteria have a credit card. Return to text

Please cite as:

Larrimore, Jeff (2016). "Holiday Spending and Financing Decisions in the 2015 Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, December 1, 2016, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.1866.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board economists offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers.